The Early 1900’s

“She said, ‘I may be blind and deaf, but I’m not blind and deaf to the injustices of capitalist society.’ She had this great conflict between with the New York Times, because she had she hated that people were watering down her radical politics she was so mad at them, because that she thought that people, they were all they loved publishing her when it was just when she was just an inspiring story but then they ignored her, or was attributed her politics to her disability… and she was infuriated by that, because she said well they treat me as brilliant. When I’m a success story but when I start saying like, you know, the profit motive is corroding society, all of a sudden the New York Times just isn’t as interested.”

Nathan J Robinson on the hidden socialist history of Helen Keller

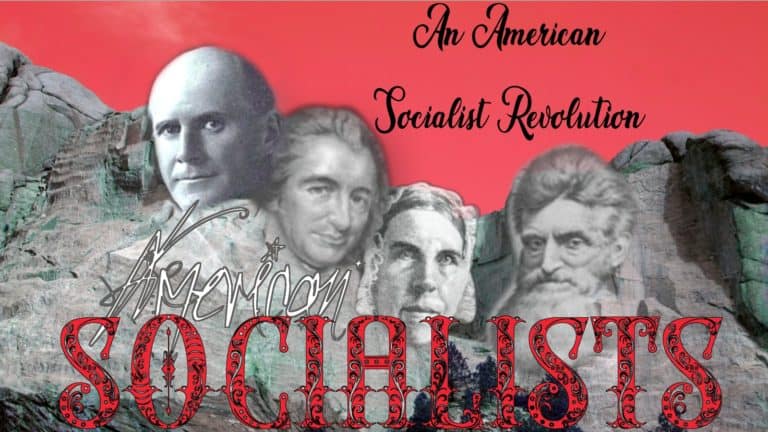

Hello Internet, I’m Jackie Fox and I’m back with a few of the more recent Socialists from American history.

Things seemed to change in the early 20th century. The Socialist Party of America was founded in 1901, itself a part of a larger socialist movement that, over the course of twenty years, made significant gains in its attempt to transform American economic life. Socialist mayors were elected in 33 cities and towns, ranging from Berkeley, California to Schenectady, New York, with Victor Berger and Meyer London winning congressional seats. All told, over 1000 American socialist candidates won various political offices. Julius A. Wayland, editor of the socialist newspaper, Appeal to Reason, proclaimed that “socialism is coming. It’s coming like a prairie fire and nothing can stop it…you can feel it in the air.”

It’s worth noting that while many women gained the right to vote in 1920, the legislation didn’t apply to all women, with Native and Chinese having to wait many more years to gain the right to vote. Black women, although legally entitled to vote, were effectively denied voting rights in numerous Southern states until 1965, by which time women’s suffrage was near universal in America.

After winning the right to vote, women would only become even more influential in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Margaret Sanger was a birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term “birth control”, opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, and established organizations that evolved into the Planned Parenthood Federation of America which accounts for much of low income women’s healthcare all over the United States. In much of her organizing she was risking imprisonment for violating the Comstock Act, which forbade distribution of birth control devices or information. She wrote articles on health for the Socialist Party paper The Call and wrote several books, including What Every Girl Should Know and What Every Mother Should Know.

Florence Kelley pioneered the term wage abolitionism. Her work against sweatshops and for the minimum wage, eight-hour workdays, and children’s rights is still quite relevant in America today. A high ranking member of the National Consumers League, she would go on to help found the NAACP in 1909. She successfully lobbied for the creation of the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics so that reformers would have adequate information about the condition of workers. In 1908 she gathered sociological and medical evidence for Muller v. Oregon and in 1917 gathered similar information for Bunting v. Oregon to make the case for an eight-hour workday.

Another socialist founder of the NAACP was W.E.B. Du Bois. He was the first African American to earn a doctorate, he became a professor of history, sociology and economics at Atlanta University. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the Atlanta compromise, an agreement crafted by Booker T. Washington which provided that Southern blacks would work and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic educational and economic opportunities. Instead, Du Bois insisted on full civil rights and increased political representation, which he believed would be brought about by the African-American intellectual elite. Throughout his lifetime, he strongly protested against lynching, Jim Crow laws, and discrimination in education and employment. Like many others I’ve mentioned, Du Bois was a prolific writer, and I actually quoted his writing about John Brown.

Victor Berger, who won a Wisconsin House seat, founded both the Social Democratic Party of America as well as the Socialist Party of America at the turn of the century. He was known for leading a group that came to be known as the “Sewer Socialists”.

As an elected official, Berger was more committed to electoralism than many of his comrades. According to historian Sally Miller,

“Berger built the most successful socialist machine ever to dominate an American city….[He] concentrated on national politics…to become one of the most powerful voices in the reformist wing of the national Socialist party. His commitment to democratic values and the non-violent socialization of the American system led the party away from revolutionary Marxist dogma. He shaped the party into force which, while struggling against its own left wing, symbolize participation in the political order to attain social reforms…. In the party schism of 1919, Berger opposed allegiance to the emergent Soviet system. His shrunken party echoed his preference for peaceful, democratic, and gradual transformation to socialism.”

Meyer London was elected to represent the Lower East Side of Manhattan in Congress. London started his political career in the Socialist Labor Party of America and would go on to establish the Social Democratic Party of America. London was active in strikes in New York and in 1901 his Social Democratic Party would join the Socialist Party of America, with London joining as a founding member. After being elected to Congress, he was one of the few to vote against entry into World War I.

The turn of the century was interesting for another reason, though it has less to do with socialism directly. In the same year that Victor Berger would found the Socialist Party of America, William McKinnley would be assassinated and Republican Theodore Roosevelt would take office as our youngest President for 8 years. When people talk about the “party shift” of the 20th century, they often mention the influence of the civil right’s movement and the Presidency of Franklin D Roosevelt as being influential. That’s what I did at least…

But the previous Roosevelt also had an influence on the process of changing the Republican Party to the Party of Nixon or Reagan. After a series of disputes with the following Republican President, Theodore came out of retirement for a third bid at the Presidency in 1912 just to run against Taft. Roosevelt formed the Progressive party when the Republicans chose not to nominate him over the incumbent Taft creating a schism in the Republican Party that cleaved its left wing and moral center like the formation of the Socialist Party of America had over a decade before. I think that these events in 1912 were the beginning of the Republicans as a fully right wing American party.

Around thirty years after the Pullman train strike, in 1918, Eugene Debs had led historic strikes and run for president four times on the Socialist Party of America ticket since the party’s formation, but the renowned orator had never given a speech like the one he delivered in a Canton, Ohio, park on June 16. “The working class have never yet had a voice in declaring war. If war is right, let it be declared by the people – you, who have your lives to lose.” This speech got him jailed under charges of sedition for speaking out against involvement in World War I. “I know of no reason why the workers should fight for what the capitalists own,” Debs wrote to novelist Upton Sinclair, “or slaughter one another for countries that belong to their masters.”

The next year, Victor Berger was also indicted under the espionage act for opposing American involvement in the war. In spite of his being under indictment at the time, the voters of Milwaukee elected Berger to the House of Representatives in 1918. When he arrived in Washington to claim his seat, Congress formed a special committee to determine whether a convicted felon and war opponent should be seated as a member of Congress, resulting in the denial of the seat to which he had been twice elected. That verdict was eventually overturned by the Supreme Court in 1921 in Berger v. United States, and Berger was elected to three successive terms in the 1920s.

Debs was no stranger to jail; he had been locked up for six months in 1894 for helping to lead the Pullman strike. Behind bars he spent his time educating himself with the works of Marx and others. “Books and pamphlets and letters from socialists came by every mail and I began to read and think and dissect the anatomy of the system in which workingmen, however organized, could be shattered and battered and splintered on a single stroke […] It was at this time, when the first glimmerings of socialism were beginning to penetrate, that Victor L. Berger — and I have loved him ever since — came to Woodstock [prison], as if a providential instrument, and delivered the first impassioned message of socialism I had ever heard — the very first to set the wires humming in my system. As a souvenir of that visit there is in my library a volume of Capital by Karl Marx, inscribed with the compliments of Victor L. Berger, which I cherish as a token of priceless value.”

Debs declared himself a socialist in 1897 and helped found the Socialist Party of America alongside Berger four years later. In 1912 he managed 6% of the national vote, which beats modern day third party socialists like Howie Hawkins, Jill Stein, and Gloria de la Riva. He was a powerful and inspiring speaker, drawing tens of thousands to his rallies despite his poor chances of winning the Presidency, and this fueled his popularity.

At Debs’ trial in Cleveland in September 1918, the prosecutor argued that Debs’ speech was “calculated to promote insubordination” and “propagate obstruction to the draft.” Debs’ lawyers conceded the facts of the case, and Debs spoke on his own behalf.

“I have been accused of having obstructed the war,” Debs told the jury. “I admit it. I abhor war. I would oppose the war if I stood alone.” He defended socialism as a moral movement, like the abolition of slavery decades before. “I believe in free speech, in war as well as in peace,” Debs declared. “If the Espionage Law stands, then the Constitution of the United States is dead.” After losing his trials, he ran for President yet again from jail in 1920 and win nearly a million votes from an Alabama prison.

After Debs’ long run as the perennial candidate of the Socialist Party of America, minister Norman Thomas took over as the Party’s Presidential candidate as the Red Scare began in America. Like Debs, Thomas ran six times and fought for a number of issues in his time as candidate, once in opposition to the Second World War. He also fought alongside Margeret Sanger for women’s access to birth control and greater rights.

The early 20th century’s Socialist Movement arose in response to America’s new industrial economy. Socialists argued that wealth and power were consolidated in the hands of too few individuals, that monopolies and trusts controlled too much of the economy, that owners and investors grew rich at the expense of the very workers who produced their wealth, and that workers, despite massive productivity gains and rising national wealth, still suffered from low pay, long hours, and unsafe working conditions. According to Debs, socialists sought “the overthrow of the capitalist system and the emancipation of the working class from wage slavery.” Under an imagined socialist cooperative commonwealth, the means of production would be owned collectively, ensuring that all men and women received a fair wage for their labor.

“They shot one of those Bolsheviks up in KnoxCounty this morning, Harry Sims his name was… The deputy knew his business, he didn’t even give the Redneck the chance to talk, he just plugged him in the stomach.”

Malcolm Cowley, The New Republic 1932

Over a decade later the Coal Miners of Blair Mountain would launch their own strike. Called Rednecks for their socialist, pro-worker rhetoric and iconic red bandannas, their little strike would become a small Civil War between laborers, owners, and the state itself. Frank Keeney, the president of the United Mine Workers of America District 17, gave a stirring speech to thousands of miners on the capitol grounds in Charleston. He told the crowd that there was no justice in West Virginia and declared, “The only way you can get your rights is with a high powered rifle!”

He was terrifyingly and prophetically right, and many would come to die in the Battle of Blair Mountain, in which the US government teamed up with strike busters to put the miners of West Virginia back to work mining their coal in conditions that often turned out to be fatal. At one point US government even went on a bombing run, slaughtering the striking workers of Blair Mountain in cold blood.

Over 10,000 miners carved a path of rebellion from Charleston to the doorstep of Logan County. Blocking their path were the entrenched forces of local sheriff Don Chafin, dug-in with machine-gun turrets guarding key passes through the steep terrain. After days of fighting, which included bombs dropped from biplanes, the Battle of Blair Mountain ended when federal troops were dispatched. https://tclf.org/battle-blair-mountain-still-being-waged

“Mine guards and miners fought it out until federal troops intervened. Over 500 “rednecks” were charged with treason, murder, and conspiracy to commit murder. The state used coal company lawyers in the prosecution, and our own governor testified against the miners. Among those charged, of course, were the leaders of the movement: Frank Keeney, Fred Mooney, and Bill Blizzard.”

C. Belmont Keeney, Frank’s Grandson

To his grandfather, the mine workers position was common sense,

“I am a native West Virginian and there are others like me in the mines here. We don’t propose to get out of the way when a lot of capitalists from New York and London come down and tell us to get off the earth. They played that game on the American Indian. They gave him the end of a log to sit on and then pushed him off that. We don’t propose to be pushed off.”

“Blair Mountain stands as a pivotal event in American history, where working men and women stood up to the lawless coal barons of the early twentieth century and their private armies and fought for their rights as Americans—and indeed, the rights of working families all over the world. It is a place where we can all be reminded that workers in this nation were literally forced to fight for their rights, and that those rights must constantly be defended or they will be lost. Blair Mountain is a beacon for all those who support American ideals of democracy, fairness, and freedom, which is what the miners were fighting for.”

Cecil E. Roberts, president of the United Mine Workers of America

Upton Sinclair was a political activist and 1934 Democratic Party nominee for Governor of California, but perhaps more importantly he was a very influential and prolific writer with a long list of professional achievements that helped changed the world. He exposed the foul meatpacking industry and yellow journalism, and much like the John Oliver effect only capable of doing more than crashing servers, this writing inspired change in the way of the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act alongside a first ever code of ethics for journalists. He is well remembered for lines like, “it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it,” which he often used on the campaign trail, and “Capitalists will not agree to any social progress completely eliminating unemployment because such a program would reduce the supply of cheap labor. You will never persuade a capitalist to cause himself losses for the sake of satisfying people’s needs.”

Sinclair’s goal was to attain what he referred to as “democratic socialism” in the United States. He wanted to return to the original idea of the American dream. He wasn’t scared to express his love for country in writing, “passionately, more than words can utter, I love this land of mine. . . . There never was any land like it – there may never be any like it again; and Freedom watches from her mountains, trembling.” Sinclair loved what the United States was supposed to stand for but was concerned that capitalism was interfering with the premises and promises of liberty that founding fathers like Thomas Paine had sought through revolution.

One of the over 100 books Sinclair wrote was a short book called: I, Governor and How I Ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future which was illustrative of his ideas – from state takeovers of farms and factories, to the establishment of a state-managed cooperative economy, to a $50-a-month pension for the elderly (approximately $1,000 in today’s money), all to be financed by a California monetary authority. His alignment with the Democrats in California was out of convenience, and he ran as a part of a larger slate of democratic candidates that was called the EPIC (End Poverty in California). Although he didn’t win his race in ‘34, many of the EPIC candidates did, in an election that helped shift California blue for decades to come. /

Despite their successes early in the century, Socialists in office in America would become much more rare moving forward, so as we move into the mid-century, we’ll have to shift away from those who wielded (or tried to wield) political power.