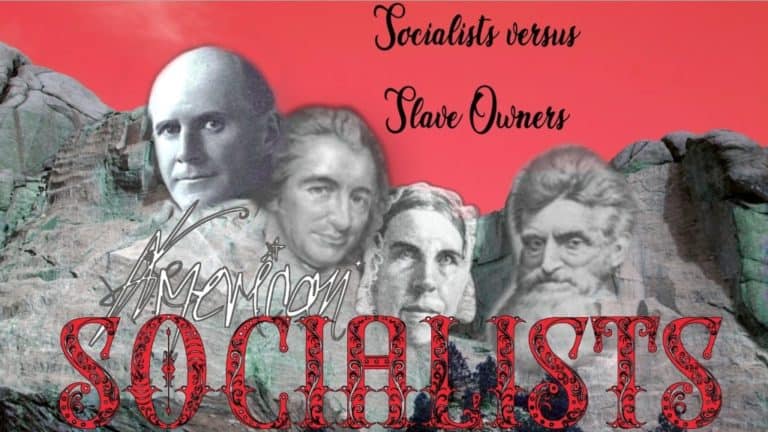

One of the first challenges the first American Socialists faced was the institution of slavery. This is not to say all abolitionists were socialists, but this was the issue that America’s first self-proclaimed socialists would fight. It was a crucial moment for socialism, a concept that had only been born that century. Slavery is the epitome of everything a socialist opposes, and the movement would have proven itself to be morally bankrupt had it not fought against the enterprise since even before its inception through people like Thomas Paine. If slavery was a moral test of socialism, then abolition was verification that socialism could change the foundations of society, and that perhaps a more just and equal world was possible.

Even in the early formation of the Republican Party as a primarily abolitionist organization, there were many social democrats and outright socialists among them. There was a strange time in American socialist history where socialists met under banners of Abraham Lincoln, their championed Great Emancipator.

Socialists had been so influential in this pursuit that it’s thought perhaps the great right-wing American tradition of denouncing all opposition as ‘socialist’ had its origins among slaveholding elites. Former Vice President John C Calhoun made the connection between the criticism of slavery to criticism of capital as early as 1836:

“A very slight modification of the arguments used against the institutions which sustain the property and security of the South would make them equally effectual against the institutions of the North, including banking, in which so vast an amount of property and capital is invested.”

Virginia Senator Robert M.T. Hunter, March 25, 1850, also recognized this connection:

“Mr. President, if we recognize no law as obligatory, and no government as legitimate, which authorizes involuntary servitude, we shall be forced to consign the world to anarchy; for no government has yet existed, which did not recognize and enforce involuntary servitude for other causes than crime. To destroy that, we must destroy all inequality in property; for as long as these differences exist, there will be an involuntary servitude of man to man. Your socialist is the true abolitionist, and he only fully understands his mission.”

Jefferson Davis, on the eve of the Civil War, agreed:

“In fact, the European Socialists, who, in wild radicalism… are the correspondents of the American abolitionists, maintain the same doctrine as to all property, that the abolitionists, do as to slave property. He who has property, they argue, is the robber of him who has not. ‘La propriete, c’est le vol,’ is the famous theme of the Socialist, Proudhon. And the same precise theories of attack at the North on the slave property of the South would, if carried out to their legitimate and necessary logical consequences, and will, if successful in this, their first state of action, superinduce attacks on all property, North and South.”

It may not be well known in history books today, but as these quotes illustrate, the slave-owning oligarchy of the time knew about it all too well.

John Brown was one of the most famous of the abolitionists, and it’s easy to see why. On trial for attempting to incite a slave insurrection in Harper’s Ferry he said this in his speech to the court,

“I believe that to have interfered as I have done in behalf of His despised poor is no wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice and mingle my blood with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I say let it be done.”

After the trial he was hung and his body dissected.

Upon his arrest, Brown had told his captors,

“I want you to understand that I respect the rights of the poorest and the weakest of coloured people, oppressed by the slave system, just as much as I do those of the most wealthy and powerful.” In many Northern communities on the day of Brown’s execution “church bells tolled; guns fired solemn salutes; ministers preached sermons of commemoration; thousands sat bowed in silent reverence for the martyr of liberty.”

One journalist wrote, “A feeling of deep and sorrowful indignation seems to possess the masses.”

He had been an abolitionist for 20 years before being executed as an insurrectionist, John Brown is the one person on this list that would be as much within the revolutionary tradition as Thomas Paine.

One of Brown’s contemporaries was Frederick Douglass, an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping slavery in Maryland, he became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, famous for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings. So, he was described by abolitionists of his time as a living counterexample to slaveholders’ arguments that slaves lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.

As Jacobin noted in a recent article bearing his name, Douglass was

“an antislavery leader who devoted his life to seeking the forcible expropriation of property worth more than all antebellum America’s factories, railroads, and banks combined. But the truth is that Douglass’s long political career was rife with contradiction. For half a century, he moved between outside agitation and mainstream political engagement; between pessimism about the depth of American racial oppression and an optimistic faith in struggle and progress; between a wary liberal individualism and a bolder embrace of utopian socialism, working-class struggle, and interracial labor organizing against the ‘tremendous power of capital.’”

While it’s unclear whether Douglass was a socialist, he fought alongside them to free the slaves, and carried on in the socialist tradition of a march towards emancipation. Seeking clues from his writing, the Jacobin article notes, “in both pieces Douglass embraces the position, held by many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Americans (though remarkably few establishment Democrats today), that “wealth has ever been the tool of the tyrant, the readiest means by which liberty is overthrown.” He anticipates arguments that “unbridled accumulation” is simply a part of human nature: in fact, the “mighty machine” of capitalist society is an innovation, which compels, rather than reflects, acquisitive behavior. And he rejects the idea that poverty is an unchangeable fact of social life: it is, rather, the ‘consequence of wealth unduly accumulated.’”

Douglass and Brown met in 1847 and wrote of meeting one another. Douglass wrote that “Brown denounced slavery in look and language fierce and bitter, thought that slave holders had forfeited their right to live, that the slaves had the right to gain their liberty in any way they could, did not believe that moral suasion would ever liberate the slave, or that political action would abolish the system.”

Brown had come to Douglass to convince him to expand the underground railroad into something more like a freedom superhighway. Douglass was not convinced the plan would work, but Brown still had a profound effect on him. He wrote:

“while I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful of its peaceful abolition. My utterances became more and more tinged by the colour of this man’s strong impressions.”

According to some, Brown’s actions even helped incite the Civil War. In 1855 wealthy white slave owners tried some dirty tricks to make Kansas a slave state. When a small war broke out between men paid to shift the election in favor of slavery and the abolitionists, Brown and his sons rode to Kansas and took a few of the men prisoner.

As W.E.B. Du Bois writes in his biography of Brown, the captives

“were led quickly into the woods and surrounded. John Brown raised his hand and at the signal the victims were hacked to death with broadswords.” Du Bois goes on, “To this day men differ as to the effect of John Brown’s blow. “Some say it freed Kansas, while others say it plunged the land back into civil war. Truth lies in both statements. The blow freed Kansas by plunging it into civil war, and compelling men to fight for freedom which they had vainly hoped to gain by political expediency.”

Three years later and with a stockpile of weapons, Brown met with a group of like-minded abolitionists and declared the independence of American slaves stating, “that the Slaves are, and of right ought to be as free and independent as the unchangeable Law of God requires that All Men shall be.” This lead to a raid on a federal armory in Harper’s Ferry, and by now you know how that ended for him: “John Brown’s body lies a mould’ring in the grave/His soul’s marching on!” (from the song made popular during the Civil War).

As Frederick Douglass later declared,

“If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery he did, at least, begin the war that ended slavery. Until this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy, and uncertain.”

Sarah Grimke may not have been an avowed socialist even though she, like Brown, was alive when the Communist Manifesto was published, but she was an abolitionist along with her sisters and was one of the first feminists and suffragettes. She persisted in her belief that the fight for women’s rights was as important as the fight to abolish slavery; and although Sarah had the desire to ‘equip women for economic independence and for social usefulness,’ they continued to be attacked, even by some abolitionists, who considered their position extreme. Abolition of slavery was achieved in her lifetime, but the fight for feminism and the women’s right to vote would only bear fruit after her death. Her fight continues and is championed by those women who would come after her. In her first oral arguments to the Supreme Court in 1973, Ruth Bader Ginsburg quoted Sarah Grimké: “I ask for no favor for my sex. All I ask of our brethren is that they take their feet off our necks.”

The fight for women’s suffrage brought a lot of notable female socialists to the front lines of activism as further expression of their political agency beyond what they were fighting for at the ballot box. Charlotte Gilman famously wrote a column on suffrage for The People and later published the semi-autobiographical The Yellow Wallpaper. However, her written body of work is much larger, with many volumes written on feminist issues relevant to her time.

Nan Sloane’s book, A Woman in the Room, recounts the stories of the female socialists within the suffrage movement. The book discusses how socialists like Margaret MacDonald, Margaret Bondfield and Mary Macarthur would often, like Grimke, find themselves at odds with less radical elements of the suffrage movement. Bondfield and Macarthur made objections on principle to a campaign that would still leave most poor, working people disenfranchised and denied the chance to use the political system to force change. Beyond just fighting for a woman’s right to vote, socialists of the time were fighting for every American’s right to freedom and emancipation.

Eugene V Debs started his political career as a labor organizer turned Democrat who earned the esteem of Democratic and Republican newspapers for his forward thinking. In 1888, Debs wrote, “the strike is the weapon of the oppressed.” The Pullman train strike he organized in 1894 was one of the single biggest labor actions in American history, stalling trains in 27 states. The rest of his story would unfold in the following century, as socialists all over the country began to take political power into their own hands.