In the last week and a bit; Stephanie Kelton has asked two questions: Why are Democrats Bragging About Plunging the Private Sector into Deficit? and Why Are We Kneecapping the Recovery? Here, I offer a root cause analysis of these questions that highlights the most profound element in all of MMT’s teaching.

It’s been known in certain intellectual circles for a number of years now that the social sciences are in crisis.

Three highlights worth mentioning here are:

- The economics discipline’s abysmal record at either being able to forecast events or even coherently explain them after the fact, particularly if those events ‘shouldn’t have happened’ (i.e. flew directly in the face of established orthodoxy).

- The ongoing replication crisis in psychology whereby the major journals find replication rates of between 25% and 62% for experiments on which orthodox theories of human behaviour are based.

- The long, embarrassing record of financial economics performing worse than chance at being able to produce gains and its stubborn, deluded retention of the bell curve as a tool for understanding price shifts when its applicability to this field has been so comprehensively obliterated by real mathematicians.

It is worth quickly expanding on this last point to illustrate the depth of farcicality at play. A bell curve illustrates systems where most-to-all variances in a system fall within three average distances (standard deviations) from the average. In plain English: everything is either slightly above or below average. Think heights and weights of humans: no one human is short, tall, light, or heavy enough to affect the overall average of a person. This, however, would not be the case in realms that follow a power-law or Pareto distribution where we compare rocks the size of grains of sand, boulders, mountains, and planets. Realms such as these have no meaningful averages since every addition or subtraction of one piece of data completely changes the character of the entire dataset.

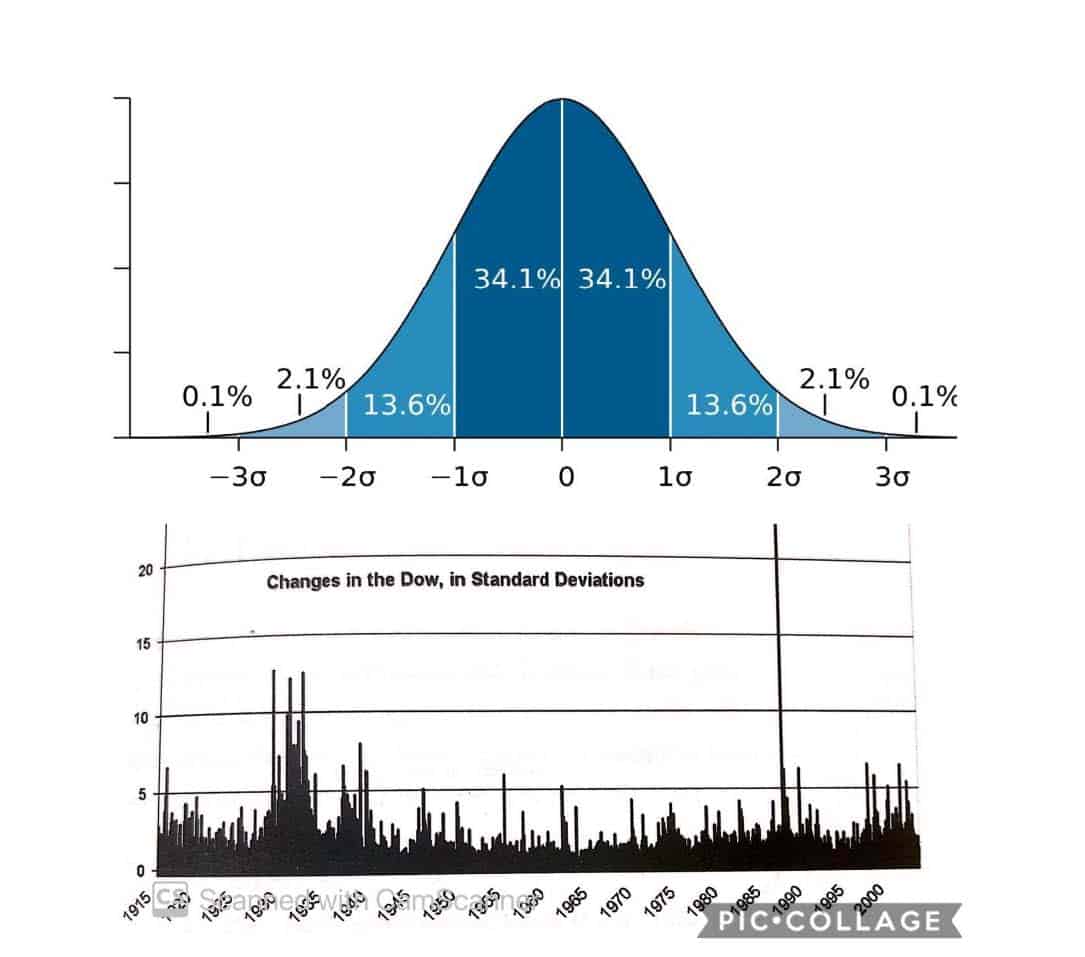

One of my biggest influences, Benoit Mandelbrot included in his 2004 title (Mis)Behaviour of Markets, the bottom chart where he measured the price changes in the Dow Jones for the entire 20th Century in standard deviations rather than the usual absolute values. If the bell curve still applied then there could not have been so many movements between five and ten standard deviations since 13.6 + 34.1 + 34.1 + 13.6 = 95.4% of experienced movements would be within 2 standard deviations, according to the orthodoxy in the top chart. Unfortunately, orthodoxy isn’t playing a game of experienced things in the first place, but that’s for main course.

And we would have needed >100,000 years of trading before we saw a movement of 22 standard deviations as in 1987. Incidentally, this was Black Monday, a day where financial institutions lost multiples more than they had ever gained in their entire history, in one day. This is a power-law realm par excellence, where one data point can outweigh the rest of the set combined.

Ironically, the social sciences’ physics envy is turning it into pseudo-science, the crude maths we use for relatively stable systems such as electrons or planetary orbits are simply not suitable for high volatility systems seen in mass human behaviour. Fractal and Chaos mathematics promise a glimmer of hope of someday being able to handle these jobs, but they’re a long way off. Anyone who can look at the above charts and still think the bell curve applies to financial economics categorically does not understand the bell curve, let alone financial economics. Yet it is still thought in virtually every undergraduate and postgraduate financial economics program to this day!

Bringing it back to today’s questions, we are once again in a place where we look to be about to feed proverbial hypertension medicine to the proverbial patient when they actually have dangerously low blood pressure because it is believed that this is what we should do. Again, regardless of what experience tells us. What Ms Kelton is asking is: why do we care so little about the experiential side of life and continuously plough on with trying to impose orthodoxy-compliant policy from the textbooks onto real life?

Let’s bring it back to some seriously practical basics here. If inflation is a function of too much liquidity / too little output then there are two dimensions we can play with here. Fine. But, as Kelton points out: if reducing the liquidity also reduces output then the entire equation will get overall worse faster!

This immediately conjures ghostly parallels from Eatwell & Milgate’s 2011 Fall and Rise of Keynesian Economics:

“Even when school-children begin to learn about fractions, one of the first things they are taught is that a fraction can be lowered either by reducing its numerator or increasing its denominator (or by doing a bit of both). But when that fraction is the ratio of the budget deficit to GDP, it is surprising how many seem to forget entirely their elementary arithmetic and proceed to speak as if the only way to reduce that ratio is to cut the deficit. This would be misleading enough—since the objective might just as well be achieved by thinking of ways of increasing GDP—but it is positively crazy if cutting expenditure may decrease GDP. This is a lesson that the European Union has chosen to learn the hard way—as governments from Greece and Ireland, through to Italy, Spain, Portugal, Germany, and Britain, are slashing public expenditures to reduce “the deficit.”

It is striking to realise that a fraction can usually be affected more dramatically and more quickly by playing with its bottom number since that will have a multiplicative effect rather than just a subtractive one.

But now I finally come to the promised main course: most policymakers have spent their lives playing around with abstractions on paper or on spreadsheets (and they seem pretty crap at that too, if their fractional maths are anything to go by!) and so their instinct is to believe that we need to dampen real output due to a dearth of money.

Let this sink in: “We should hobble our capability to make real stuff due to a shortage of units of a collective and agreed upon figment of imagination”.

If money is, and was only ever, a representation of real value after the fact, then how have we let it backwash the wrong way and become convinced that we should produce less value in order to save it?

Why would policymakers opt to leave factories and warehouses, that produce real wealth, lying idle in order to hoard points on a scoreboard that are in no way finite, when this very decision is what would bring about more material poverty?

The original fraction of: the volume of money / real goods and services gives us a clue here. Which of the two elements of the fraction would you say are more real?

I’ve been called ridiculous for asking these kinds of questions before so if you’d prefer: which of these elements is less reliant on the buy-in of human imagination in order to exist? If inflation is a function of money and stuff, why overemphasise playing around with the money and its interest rates to the neglect of real physical output of goods and services? When it comes to the human confusion between abstractions and social constructs that need human buy-in to exist, and material realities that require no such thing to exist, there are some incredibly illuminating perspectives offered to us by epistemology, the philosophy of science, and neuropsychology. In the interests of holisticism and breaking down the silos that I feel serve as barriers to our enlightenment: I’d like to skim on the key points.

Epistemology & Philosophy of Science

These fields are concerned with the study of how we come to know truth in the world. They are marked primarily but not exclusively by the debates about whether ideas or experiences are the best routes to knowledge. These sides went on to roughly approximate the later schools of rationalism and empiricism that came to advocate for ideas and experiences respectively as the primary ways to truth.

Plato and Aristotle’s dialogues and debates are the ones traditionally referred to when it comes to this field but less well known are what I would call the proto-empiricist, Heraclitus and the proto-rationalist, Parmenides. These lived in 6th and 5th century BC Greece. Heraclitus was sceptical of placing our theories about experience above experience itself and stated that “whatever comes from sight, hearing, learning from experience: this I prefer.” Parmenides, on the other hand, posited that thought and being are the same thing, what can be thought must be, what cannot be thought cannot exist. Most importantly: what follows from logic, however much it flies in the face of experience, must be true.

Plato carried on later in this Rationalist tradition by all but claiming that the geometry we play with in the sand is more truthful and eternal than the stars themselves in the heavens. Plato’s student Aristotle, vehemently disagreed and emphasised the importance of experience, experimentation, curiosity, and observation in order to test if the rationales and narratives we construct are correspondent with the outside world or not.

I have two fundamental issues with the Rationalist school:

- It hubristically expects nature to conform to the brand of rationality that we have in our heads and dares to audaciously tell it that it is wrong for not conforming and not having read the textbooks.

- All ideas must come from learning and experience at first, but at some point, ideas can congeal into beliefs or orthodoxies that impair any new learning after that point. This is a form of order principle bias where A is believed over B purely by virtue of having been heard or seen earlier in sequence.

I don’t think it too harsh to approximate Rationalism with inward-lookingness and Empiricism with outward-lookingness.

For balance, I should mention that Rationalism is quite appropriate for the formulation of law since it is concerned with how things ‘should be’. This is relevant to our discussion since, if you trace back the lineage of virtually all non-STEM academia, you are brought back to the West’s first ever University in mediaeval Bologna, Italy; a canon law school that went heavy on the teaching of Plato’s Rationalist philosophy. This teaches us that Rationalist/Law-type study became the cookie-cutter for academia in general (with the exception of STEM).

The problem with the social sciences, then, is that they’re children of Law rather than children of Science. This is an unfortunate heritage for disciplines that first need to understand how things are before moving on to making things how we would like them to be.

Neuropsychology

Until Iain McGilchrist, the study of brain hemispheric differences had fallen into some disrepute. This seems due to the field’s hijacking by pop-psychology and other business/motivational charlatans. Many of the believed differences came out in the wash as myths. But then a more unfortunate myth emerged: that there were no differences or significance to the differences in how the brain hemispheres process our worlds. McGilchrist has gathered reams and reams of evidence based on studies of increased or decreased activity in one or other hemispheres due to strokes, lesions, and any number of conditions and pathologies.

There are many important differences between the two brain hemispheres but there is one that is both extremely relevant for this discussion and also seemingly a corresponding biological hardware design that gives rise to the philosophical softwares discussed in the above section. The right hemisphere does the experiencing. It works primarily with sensory inputs and is capable of vigilance to the unknown.

The left brain does the abstracting. It works primarily with language, theory, and other symbologies. It is incapable of experiencing the outside world for itself or working with anything that it doesn’t already know, it relies on the right hemisphere to pass it new information which it then must convert into language, symbols, or other abstractions.

The worry seems to be that, since there is such emphasis in Western society on literacy and not what is beyond literacy that literacy can unlock for us, there can be a tendency among people who don’t do or make things in the physical world to drift into believing abstractions are the real thing, and that experiential reality is a mere representation:

“In a clever and audacious, one might say hubristic, inversion, the left hemisphere now seems to imply that what is purely conceptual is what is real, and what is experienced, at least by the senses, is downgraded, and amazingly enough actually becomes the ‘representation’!”

– Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary

McGilchrist describes a phenomenon that I’d called ‘Abstraction Flipping’ which I’d been suspicious of quite some time ago but he is able to analyse it in far greater depth than I.

Conclusion

Economics doesn’t know which way is up because it is using the tools of law to do the jobs of science. It doesn’t care what there is to be experienced in the wild relative to how much it cares about its incumbent beliefs, orthodoxies, and ideas.

It believes that playing around with interest rate, liquidity levels, or availability of credit will somehow reach out of the spreadsheets into the real world and solve the material issues of shortage, price gouging, or supply chain issues.

Since it is practised by people who have mostly worked with abstractions all their lives, they tend to believe that material realities are less real than social constructs.

Abstractions are invented and agreed upon by us but often become runaway Frankenstein’s monsters when we forget that we made them up. This is why we allow an imagined shortage of money to stop us from producing the very things money was only ever supposed to represent. This point is the most important kernel of MMT, to my mind. In fact, it was MMT’s pointing out that material well-being is more real than abstract money that led me down many of these rabbit holes in the first place!

Bibliography & Recommended Reading:

Incerto Series (Fooled by Randomness, The Black Swan, Skin in the Game, Antifragile, The Bed of Procrustes)- Nassim Nicholas Taleb

(Mis)Behaviour of Markets – Mandelbrot

The Master and His Emissary & The Matter With Things – Iain McGilchrist

The Fall and Rise of Keynesian Economics, John Eatwell & Murray Milgate

1 thought on “Bad Medicine Root Cause Analysis: Abstractions Are Killing Us”

Pingback: Bad Medicine Root Cause Analysis: Abstractions Are Killing Us – Critical News Autoblog