In all the coverage of the labor shortage by mainstream, corporate media, the human element of the power dynamics of waged labor in the COVID-era has steadily been missing from popular analysis. In order to dispel the sensationalism and get an idea of the real current state of jobs and labor in the United States, I interviewed two people, each on opposite sides of the country, to get an idea of their experiences and impressions.

My first interview was with Joey, a worker who lives in Ohio. Joey had been placed in an administrative role dealing with Ohio unemployment claims. Joey illustrated there were consistent system issues preventing remote employees, like himself, from logging into work. His employer was consistently uninterested in helping employees resolve their system and password issues. Joey indicated that, in his experience, they chose to blame employees for the issues they were having rather than help resolve the same issues.

Due to these simple technical issues, Joey and other workers went days, even weeks, without pay. Joey also told me the office threatened to ensure that anyone who had worked for them would be ineligible for Ohio unemployment benefits if they later applied. Because of these problems, the staffing company that helped Joey be placed in the role offered to move him to another client’s open positions. This new employer, McGraw-Hill Education, had promised a fully ‘work from home position’ in the interview and hiring process.

However, the day before the orientation class was to start, the McGraw Hill recruiter emailed Joey, indicating he had to come in-person for orientation. Having been unemployed during the transition between jobs, Joey agreed to do in-person orientation, but stressed he would need to work from home after that. He also told me he doesn’t have a car for transportation, so going into the office every day wasn’t feasible for him, which is the reason he looked for work from home positions to begin with.

The instructor of the orientation class had promised Joey that after the three weeks of orientation and nesting, he would be able to work from home. This promise came after Joey had mentioned that, during the interview and hiring process, he was told the position would be remote, work from home. Once he was through orientation, Joey’s manager refused to let him and the other two employees who had trained with him work from home, despite the manager working from home as well as hundreds of other employees doing the same and similar work that Joey was to perform.

“Workers, management, they are just humans. Garry Qualters, I mean he seemed like a decent guy. He seemed like he’s been in management for a while but at the end of the day he is just human, he has a temper tantrum and then lies about it and I lost my job over it.”

Joey

Ultimately, Joey was fired via phone call for asking his manager, Garry, questions regarding the work from home placement. Joey needed the work from home environment he was promised repeatedly, and Garry refused to honor his company’s end of the bargain. This has left Joey in a precarious position financially. Joey told me that if he doesn’t find a job by the end of July (2021), his bills will snowball and leave him in a far worse position.

“At the end of the day, we don’t have any dignity or control as a worker in our lives.” – Joey

Author’s note: I reached out to the manager, Garry Qualters, for comment and received no response.

The second person I interviewed was Graham from Medford, Oregon. Graham and I were able to not only speak about the power dynamics of wage labor in their area but also how those dynamics play into other issues such as homelessness.

Graham’s story is a little different. They were sent home from work at the beginning of the pandemic, and at the time they were a service industry worker at a restaurant.

Interestingly, both Joey and Graham have noticed an increase in starting pay for service industry jobs in their respective areas. In Joey’s case, jobs were starting at $10-12 per hour and now are closer to $15-17 per hour. In Graham’s case, jobs were hovering around the Oregon minimum wage of $11.50 (now $12 as of July 1st, 2021) and are now floating around $14.75-15 per hour. Graham attributes the worker shortage as the reason for the moderate increase in starting wages. (Oregon is also interesting as the state has a three-tier minimum wage system, depending on how “urban” the county is.)

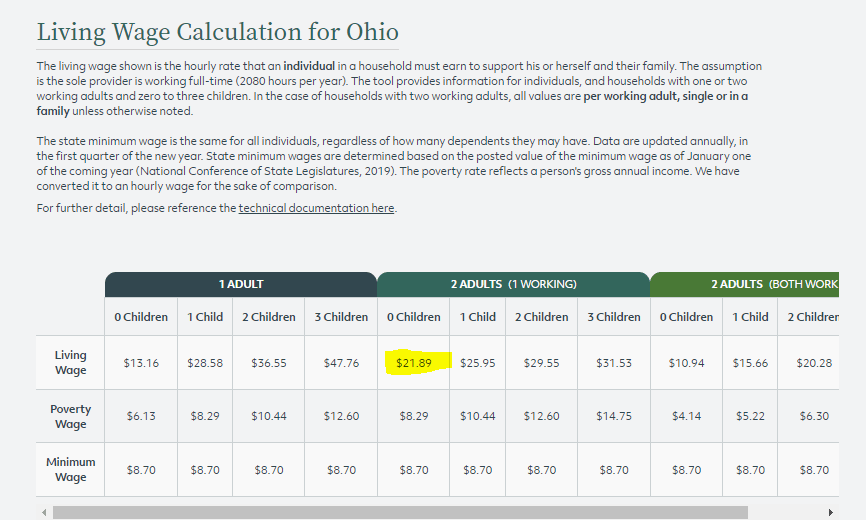

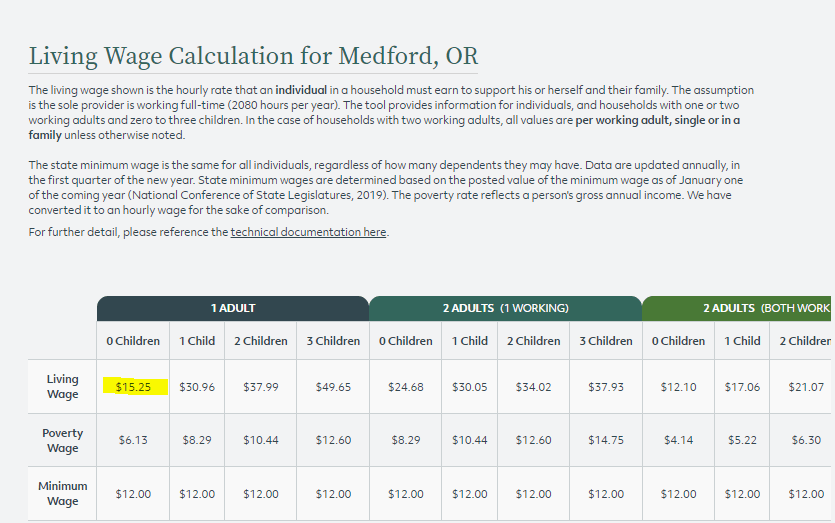

Mathematical analysis by the MIT Living Wage Calculator shows the current minimum living wage for Joey’s situation is $21.89 an hour.

In Graham’s case, the minimum living wage for their situation works out to $15.25 per hour for full-time work.

The MIT calculator illustrates the absolute minimum each type of household needs to bring in per worker for only the basic necessities.

From the “about” page describing the living wage calculator:

“Analysts and policy makers often compare income to the federal poverty threshold in order to determine an individual’s ability to live within a certain standard of living. However, poverty thresholds do not account for living costs beyond a very basic food budget. The federal poverty measure does not take into consideration costs like childcare and health care that not only draw from one’s income, but also are determining factors in one’s ability to work and to endure the potential hardships associated with balancing employment and other aspects of everyday life. Further, poverty thresholds do not account for geographic variation in the cost of essential household expenses.

The living wage model is an alternative measure of basic needs. It is a market-based approach that draws upon geographically specific expenditure data related to a family’s likely minimum food, childcare, health insurance, housing, transportation, and other basic necessities (e.g. clothing, personal care items, etc.) costs. The living wage draws on these cost elements and the rough effects of income and payroll taxes to determine the minimum employment earnings necessary to meet a family’s basic needs while also maintaining self-sufficiency.

The living wage model generates a cost of living estimate that exceeds the federal poverty thresholds. As calculated, the living wage estimate accounts for the basic needs of a family. The living wage model does not include funds that cover what many may consider as necessities enjoyed by many Americans. The tool does not include funds for pre-prepared meals or those eaten in restaurants. We do not add funds for entertainment, nor do we incorporate leisure time for unpaid vacations or holidays. Lastly, the calculated living wage does not provide a financial means to enable savings and investment or for the purchase of capital assets (e.g., provisions for retirement or home purchases). The living wage is the minimum income standard that, if met, draws a very fine line between the financial independence of the working poor and the need to seek out public assistance or suffer consistent and severe housing and food insecurity. In light of this fact, the living wage is perhaps better defined as a minimum subsistence wage for persons living in the United States.”

(Glasmeier, Amy K. Living Wage Calculator. 2020. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. livingwage.mit.edu)

Despite more than 600,000 deaths (and counting) due to COVID-19 in just over a year, deaths above and beyond the normal death rate in the United States, causing a literal shortage in expected desperate workers, and business incrementally raising wages to increase their attractiveness as an employer, the market still cannot, or will not, offer living wages. In the case of both Joey and Graham, the wages being offered don’t match up to the wages needed to eke out a bare subsistence of living. As the MIT researchers explained, they don’t calculate any form of leisure or recreation into their living wage model. Their version of a living wage is literally the bare minimum for the described household to survive, assuming typical food, health, and housing needs.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) himself set the precedent that the minimum wage is meant to be a living wage.

“In my Inaugural I laid down the simple proposition that nobody is going to starve in this country. It seems to me to be equally plain that no business which depends for existence on paying less than living wages to its workers has any right to continue in this country. By “business” I mean the whole of commerce as well as the whole of industry; by workers I mean all workers, the white-collar class as well as the men in overalls; and by living wages I mean more than a bare subsistence level-I mean the wages of decent living.”

Franklin Roosevelt’s Statement on the National Industrial Recovery Act – June 16, 1933

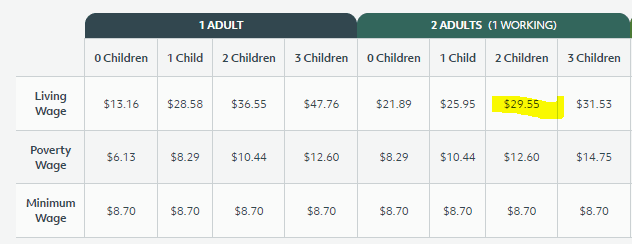

In FDR’s time, as well as the decades that followed, the nuclear family was very much the foundational unit of American society. While of course there were other types of families, the two-parent /two-child model was catered to in culture and policy. As such, it is incredibly fair to assume that the minimum wage standards of FDR’s time were catered to these four person / one worker households as the standard. According to MIT’s living wage project, in Joey’s area, the traditional nuclear family would require a minimum wage of $29.55 an hour for a 40-hour workweek to provide a minimum living.

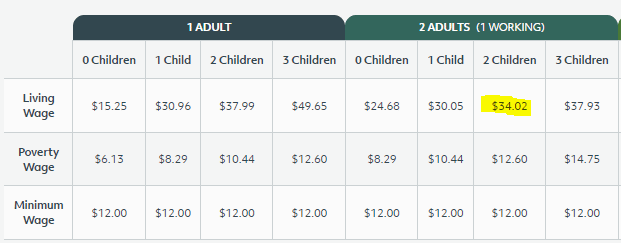

According to the same, a similar household in Graham’s area would need $34.02 per hour for the same work schedule as above.

Again, these figures provide enough income for the bare minimum of living: staying alive. They don’t factor in hobbies or recreation, or non-typical levels of need due to mental or physical health, food allergies, or other differences in human existence. FDR’s vision for minimum wage was one of every worker being able to afford more than mere survival.

In other words, wage slavery is alive and well in the United States. FDR wasn’t perfect, of course. Most of FDR’s policies and advocacy were a product of him being forced left by the strength of trade unions and militant communists and socialists in the Depression-era. Without those radicals pushing for revolution, the FDR era would have looked much different.

When talking to Graham, they were able to highlight how mutual aid has helped keep people afloat. They shed an interesting perspective; people of all political persuasions attempted their own forms of mutual aid. Additionally, there was community-building in the face of the pandemic that would ultimately get disrupted by the city of Medford and its police. Graham told me most of the mutual aid projects started after a massive wildfire ravaged the area prior to the pandemic.

“This wildfire spread really fast, burned down like 3,000 homes, and most people never got an alert or a warning. The county actually didn’t activate their own warning system. They had been defunding fire departments and firefighters for the last several years too. What they had been prioritizing was trying to build a bigger jail.”

There were several projects that can be loosely described as “mutual aid” in the Medford area, including ones sponsored by right-wing elements.

“The real change that I’ve seen is really that mutual aid has really kind of changed the face of community and local politics here because the mutual aid efforts after the fire were massive, and they were entirely just self-organized. They weren’t all left-wing oriented.”

Unfortunately, left-wing elements were accused of being bad actors by members of the community.

“We [left-wing activists] got accused of being like the ‘antifa’ coming in from somewhere else to bring in a bunch of homeless, that we [antifa] started the fire. These are narratives they were floating around.”

The right-wing elements involved in mutual aid included biker gangs interconnected with the MAGA crowd.

“Bikers Against Child Abuse, I think, were involved in a mutual aid project. Some local biker gangs and some right-wing MAGA groups, they’re all kind of interconnected, they had a massive clothes donation going on at one of the Walmart’s, just in the parking lot of Walmart, it was huge, it was a lot like a flea market.”

Further, we discussed what it was like to be a service worker at the beginning of the pandemic. Many workers, including Graham, ultimately were forced out of jobs out of concern for their own health and safety.

“Customers got more aggressive. I think a big reason the customers got more aggressive is that I think a lot of them lost money. You know, I think a lot of like small business, you know owner class, homeowners, these people they all seem to be resenting because I spend a lot of time on local social media and there’s a lot of local businesses just lashing out.” – Graham

In terms of safety, Graham highlighted how their employer was pressuring employees not to enforce the state laws regarding the mask mandates, and ultimately not allowing employees to even recommend their customer wear masks to curb the spread. Graham told me that, as this informal practice continued, workplaces became flooded with more and more employees who believed the pandemic – and the virus – were fake. This progression only compounded the dangers service workers face in the COVID era. Race dynamics also played a role.

“In their words, they [the small business owners] really feel like they’re under attack. That’s also because we had our first ever black lives matter, the first mass protest in Medford happened after George Floyd. It was like 1500 people and that’s unheard of in this town. Like, it just – that’s not something that would normally happen and I think a lot of the white people in this town felt ‘like wow I didn’t know there were so many non-white people here’.”

Graham and I also discussed how Medford was a sundown town. Black people were also excluded from owning property and settling in the state at its founding. Here is some analysis illustrating how the original Oregon state constitution was designed:

“Oregon’s small white population had voted on July 5, 1843, to prohibit slavery by incorporating into Oregon’s 1843 Organic laws a provision of the 1787 Northwest Ordinance: “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” The law was amended, however, on June 26, 1844, by the provisional government’s new legislative council, headed by Missouri immigrant Peter Burnett. As amended, the law prohibited slavery, gave slaveholders a time limit to “remove” their slaves “out of the country,” and freed slaves if their owners refused to remove them.

The effect was to legalize slavery in Oregon for three years. Moreover, once freed, a former slave could not stay in Oregon—a male would have to leave after two years, a female after three. Any free Black who refused to leave would be subject to lashing, a provision that was known as “Peter Burnett’s lash law.” Burnett, who later became the first U.S. governor of California, gave this explanation for his support for the law:

“The object is to keep clear of that most troublesome class of population [Blacks]. We are in a new world, under the most favorable circumstances and we wish to avoid most of those evils that have so much afflicted the United States and other countries.”

Because the lashing penalty was judged to be unduly harsh, the council substituted a lesser penalty later that year, and voters rescinded the law in 1845 before anyone could be punished. The law did discourage at least one settler—George Bush, a Pennsylvania-born free Black who had been a successful farmer in Missouri. After arriving in Oregon with his wife and six sons, he decided to settle north of the Columbia River near Puget Sound, out of the reach of the 1844 Oregon law.

The second exclusion law was enacted by the Territorial Legislature on September 21, 1849. This law specified that

“it shall not be lawful for any negro or mulatto to enter into, or reside” in Oregon, with exceptions made for those who were already in the territory. The law targeted African American seamen who might be tempted to jump ship. The preamble to the law addressed a concern that African Americans might “intermix with Indians, instilling into their minds feelings of hostility toward the white race.” The law was rescinded in 1854.”

(Source: https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/exclusion_laws )

When I asked Graham, “What’s your impression of the state of class consciousness and labor awareness in your area now that COVID’s hit?” they had this to say:

“Just speaking for my area, I would say everyone, and I mostly interact with other poor, working-class people, I don’t spend a lot of time talking to – there’s a university town near here called Ashland, it’s like a liberal haven, it sucks, and then Medford is really just like the industrial… most people I that I know of are making, you know, hourly wages and/or are homeless. You know, I know a lot of – I spend a lot of time working with homeless folks, or unhoused folks. They’re [working class people in Medford] all aspiring capitalists. Like everybody has these big dreams to – you know they all understand how capital works, they all understand you got to acquire something and then start, you know, something that will make money out of itself. You have to get your hands on some land. I don’t think there’s a lot of, it’s not a lot of entrepreneurial types. It’s really more about like ‘yeah I want to get me some land.’ Living off the land is a wildly popular idea around here. Everyone’s dream around here is to get out unto the countryside and grow their own food… it’s very anti solidarity.” – Graham

Graham and I also discussed further the nativism and isolationism of local politics in Medford.

“This is very like kind of rebel, you know, anti-cities, anti-federal government.” – Graham

Going further, they indicated there is a strong sentiment of “employers are job creators” in their area, and the unhoused people they work with deal with a lot of shame and internalized hostility to the poor, with homeless individuals believing they aren’t like “those other” homeless people. Graham also told me about the structural impacts of the racism Oregon was founded on, indicating there are “African American families who’ve been homeless for three generations.”

Circling back to an earlier point in the interview, Graham indicated that in the face of restaurant shut-downs, owners and workers alike banded together to feed people in the community.

“A project that was started basically in response, the restaurant workers and restaurant owners didn’t have much else to do because they all had to shut down. So, they just organized like thousands and thousands of meals. They were delivering meals everywhere they could, they had more meals than they know how to give out and there was so many different mutual aid sites that got set up – they were collecting meals for people.”

The pandemic at-large provided many examples of people banding together to exchange goods and services outside the confines of the status-quo capitalist markets. Examples like the ones Graham told me about are compelling evidence that we can evolve our methods and relationships to form a society that cares. We can take care of each other; the potential is there. This is despite decades of anti-communism and modern faux-socialist politicians that claim “socialism is this” while advocating for welfare state capitalism. The lessons of Joey and Graham’s stories teach us much about what we can do for each other and what to avoid if we take the time to learn.