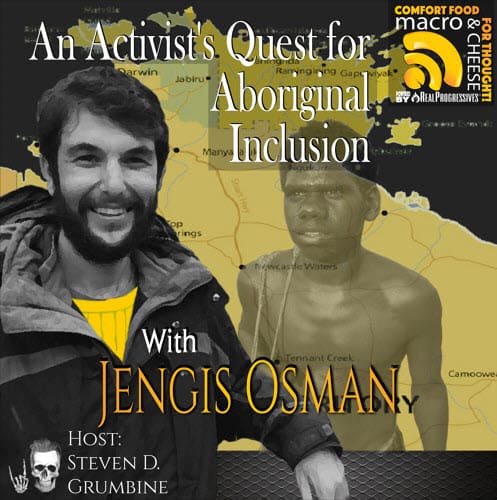

Episode 76 – An Activist’s Quest for Aboriginal Inclusion with Jengis Osman

FOLLOW THE SHOW

From the mountains of Cyprus to the Australian outback, Jengis Osman’s path led him to Modern Monetary Theory.

Our guest is Jengis Osman, an activist and labor organizer who was led to Modern Monetary Theory through his life experiences and those of his family and the people he works with. After graduating from university, he struggled to find work and questioned why it had been easier for his grandparents who had immigrated to Australia from wartorn Cyprus in the 1970s. When he taught English to new immigrants, they asked the same question: why aren’t there enough jobs?

Jengis now lives in the Northern Territory, a remote section of Australia. The effects of austerity are always harshest on the most vulnerable groups, but the living conditions of Australia’s indigenous population also reflect that country’s unique history of brutal colonial oppression. Before colonization the people had an abundance of food and water; their kinship systems worked for them. The colonizers tore communities apart with forced relocation to different regions with different customs and a foreign language. Children were uprooted and sent to mission schools far from their families. Colonialism effectively made slaves of the indigenous people and austerity assured their continued suffering.

When Jengis discovered Bill Mitchell’s blog (bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/), the pieces began falling into place. Much of this interview takes us through the MMT fundamentals that brought reality into focus for so many of us, starting with the difference between a currency creator and a currency user. Jengis talks about Pavlina Tcherneva’s example of the “hut tax” imposed by the British in Malawi as a coercive measure that provided the colonists with a labor force by creating a need for the pound sterling.

Understanding that taxes don’t fund government expenditures at the national level leads to awareness of the vast array of unnecessary political choices that cause pain at every level, including unemployment and homelessness. Fracking in the Northern Territory will damage the water supply and prolongs the negative impact of fossil fuels. Yet when the central government doesn’t spend enough in the territories and states, regional governments are forced to find private investors whose interests don’t align with that of the community. This brings us back to the difference between a currency creator and a currency user.

Steve often asks our podcast guests how they introduce MMT to the uninitiated. Jengis talks about money as akin to points on a scoreboard — the referee cannot run out of them. Money is a measure, like an inch or a mile. Those numbers are a statistical artifact and without a context, they make no sense. The economy isn’t an abstraction that sits above us and is not a “thing” we should be working to serve. The economy is us. We want to focus on achieving real outcomes, like employment opportunities, tackling climate change, and creating the kind of world we want to live in.

Jengis Osman currently works as a union organizer. He has had many occupations over the years including a substantial time unemployed as neoliberalism has decimated the idea of secure employment, providing sufficient work for all and forced education and training onto the individual rather than a collective responsibility. These jobs include a terrible stint in the retail sector, a call center as a researcher, a garbage man, and an ELICOS teacher.

Check out his blog: jengis.org/

@JengisO on Twitter

Macro N Cheese Episode 76

An Activist’s Quest for Aboriginal Inclusion with Jengis Osman

Jengis Osman [intro/music] (00:03):

How is it that we can impose a ridiculous set of criteria, in order to give someone, with below subsistence living, you impose this system of, well, you need to work to earn a living, and this is what we define work as, and then you use a really terrible institutionalized arrangement, that then quarantine their income and effectively make them slaves.

Geoff Ginter [into/music] (00:42):

Now let’s see if we can avoid the apocalypse altogether. Here’s another episode of macro and cheese with your host, Steve Grumbine.

Steve Grumbine (01:34):

All right. And this is Steve with Macro N Cheese. My good friend Jengis Osman is joining me so that we can talk a little bit about Modern Monetary Theory from an activist standpoint, from a lay person’s standpoint, from a human being that has to live with the results of bad economics. Jengis is a union organizer in the education sector based in a very remote part of the world, the Northern territory Australia.

He was previously an English as a second language teacher, teaching refugees, when they arrived in Australia, he studied economics in his senior years of high school and had many unanswered questions. He forwent study in the area and ended up with an arts degree and English major, un and under-employed for half of his studies, and after graduating, he would take odd jobs and whatever work he could find in efforts to survive.

He stumbled across MMT academic Bill Mitchell’s blog, and began to apply MMT insights to his own precarious existence, and that of many of the students he was teaching. So without further ado, I bid my fellow traveler, Jengis welcome, sir. Thank you so much for joining me.

Jengis Osman (02:51):

Thank you so much for having me.

Grumbine (02:54):

So we’ve been friends for some time now, and I’m always fascinated by the things you post. And I just felt like this was a really neat opportunity to get a totally different story to come onto Macro and cheese. And we usually have, you know, some of the early developers of Modern Monetary Theory joining us and some of the second generation.

It’s not often that we get to have people who are lay people who have come into the understanding, and it’s really exciting to have this opportunity to talk to you. So tell me, how did you come about learning about Bill Mitchell’s blog to begin with what brought you to MMT?

Osman (03:37):

Well, I studied economics in my senior years of school and you had an interest in it and I fell away from economic study because there was a lot of things that didn’t make sense to me. And then years later I stumbled across Bill’s blog. I think it was a Facebook post from a friend. And one of those first posts was something that was titled taxes, don’t fund expenditure. And I went, oh, wow, that’s how I thought about taxes.

It didn’t make sense to me all those years ago. And I was trying to grapple with the purpose of bond issuance, and I just thought it was something to do with inflation. And I didn’t think I was clever enough to understand it until I gave up on economics and I studied English and became a English language teacher, but then suddenly all these unanswered questions I had all those years ago, started to be answered, and I started to piece together all this other information.

So, when I stumbled across Bill’s blog, I had graduated and I think I’d been three or four years out of university and I didn’t have any secure work. It was sort of working from job to job, and whatever you could get, and I did all these different things, and in the end, I think I got a job working for a local council and I was driving the garbage truck and doing odd jobs and maintaining the parks and maintaining the beaches and things like that.

It was not what I thought I would be doing when I was studying. And you think to yourself, when you’re a student, well, I’m in a precarious situation now, but I’m here. And at the end of it, there’ll be a reward. There’ll be some sort of job security and an income at the end. And I won’t have to, you know, live off two minute noodles and that, that didn’t happen. I graduated and I went, I’m still living off two minute noodles and I’m still in share housing, and I had no money, and I had traveled and I had studied overseas and I was very fortunate, but it was still a very precarious existence.

I didn’t have what my father had or my grandparents, were immigrants, I didn’t have what they had, and you ask yourself those questions. You say how is it that my grandparents, with no education, and barely any literacy skills, they were from a remote village, able to migrate to Australia and find work. And here I am, and I grew up in a fairly privileged household, there was never any insecurity and we had an abundance of food and it was by no means a precarious existence.

How is it that I, in my adult life, am struggling to achieve what it is they did. And so I found Bill’s blog and you started to ask yourself, well, what are the systemic causes of why people have job insecurity? Why is it that we have unemployment? Why do we allow that to happen? And so I thought to myself, well, I can understand a difference between an issuer of a currency and a user of a currency and an issuer, just by sheer logic, has to spend anything in the first instance.

So it’s spending creates new money and taxes and bond issuance is done after the fact. You need a story to reconcile with, what taxes are for, and Pavlina’s work in this area, I found really interesting to use as an example of a hut tax. And you make a distinction between a non-monetary based society and a monetary based society. And she uses the example of when Britain colonized Malawi, and the British wanted to use the indigenous population as labor.

But when you have a subsistence living and you don’t have money, you’re not employed and you’re not unemployed. So you need to somehow coerce that population into desiring the currency. It’s useless just to tell them, if you work for me, I’ll give you this worthless bit of paper. And that made sense to me, and so what the British did was they imposed a hut tax, which is a coercive mechanism that says, well, if you don’t pay me so much pounds, as it would have been, at the end of each month, I’m going to kick you out of your accommodation by force.

Well then suddenly, if you don’t have agricultural produce or something, that issuer desires, you become a laborer, and they got them creating all sorts of textiles and all these different goods for the youth to get back home in Britain. And that just made sense to me. I went, wow. So that’s one of the most fundamental purposes of taxation is not to fund a government expenses.

It’s a coercive power to organize what’s real. And I think I got to realize at the end of all of this, that it’s the goods and the services and the skills of the labor force that creates your wealth. It’s not a series of arbitrary numbers in spreadsheets. Provided that those real resources exist, you can always deploy them for some sort of public purpose, and you can always create labor and employment. Employment itself, turns out to be this social construct and it doesn’t have to be in pursuit of a profit motive.

And then you get to question, well, then if profits aren’t necessary to fund government expenditure, what is profit? And you ask yourself those questions.

Grumbine (09:30):

Yeah. So let me ask you a question with that in mind. The labor story is very important because clearly within that currency, issuer tax driven money that you’re describing, a lot of us and, you know, the way we described it in the beginning as you spend a lot of time as un or under employed, this is a global phenomenon. It’s not just an Australian phenomenon, it’s not a US phenomenon, this is a Fiat phenomenon.

And as we’re talking through this, I keep coming back to my own story of how I learned MMT. You know, it was personal trial and tragedy. That brought me to a deep understanding of why it was so important. Let me ask you, what are some of your insights in terms of your particular station, as you watched your grandparents excel, and you thought to yourself, hey, I should be able to do better than this, I’m in university, I’m trying to better myself and yet here I am still struggling. What were the insights that drove you to really grab hold of the truths that you were just describing?

Osman (10:42):

I think it was watching not only myself, but my friends and different family members struggle as well. And the students that I was teaching, they were these groups of refugees who had no English language skill whatsoever and were often illiterate in their own language, and lots of students from Afghanistan and Syria, the Congo. And one of the questions that most of them asked me, in broken English, was where can I find work?

And I would pause, and I didn’t know how to answer that question, because I struggled to find work. And if me, as someone who grew up in Australia and was educated and held a degree, a degree that turned out to be not worth a lot, but held a degree, nonetheless, struggled to find work, what answer am I going to give to a refugee who had been in Australia for one week? Where do you find work?

And I had been through the unemployment system in Australia and it’s just a pernicious system that punishes you. And I can remember as part of receiving your dole, you have to jump over all these hurdles and you have to demonstrate you’re looking for work. I would do that. And I was living in Newcastle, which is East coast of Australia, just a few hours North of Sydney.

And there literally wasn’t enough work to meet the demand or the desired hours for the population. And I’m applying for the same job every week. And I’m thinking there’s literally only maybe four or five jobs that, are suited to my qualifications, in a good month. And you would apply for them and mostly hear nothing. And you would contact the employer and they’d say “Oh, yeah. And lots of these jobs, are at the university, and the university often didn’t have the funds to employ someone, but would still advertise for a job.”

It was this ridiculous nonsensical system. And I started to think, well, what is the point of all this, sort of running around in circles? I’m applying for work that doesn’t exist or trying to look for work that doesn’t exist. And applying for jobs where the employers don’t have the funding to pay for those jobs. And I’m required to demonstrate that I’m applying for these jobs in order to receive below subsistence living. And I applied that to the situation that my students were in once I found employment.

And I’m thinking how on earth, is someone with no language skills or none of that cultural understanding of Australia, and the country that they’ve immigrated to, supposed to navigate through the system and why don’t we have structures in place to help? Well, not just people like me, I’m articulate enough to realize when someone’s trying to exploit me, but why don’t we have systems in place to help people that can’t articulate for themselves.

And then I thought about my grandparents and I went well, they were in the same situation, they escaped a war torn country, and they had no English language skills, yet they had, employment opportunities when they arrived in Australia, which would have been in 1970. And I started to read up on the job guarantee. And it made sense from that social perspective that, well, hang on employment itself is a social construct. And we go back to that story of money or that liability creates the unemployed. And then that spending creates the employed.

And so you get back to that story and that made sense to me. So unemployment then is insufficient spending. We just haven’t spent enough to employ everyone. And then what do we get them doing? And you start to ask yourself those questions. And then you grasp that the issuer has to spend first before anything else can happen. And all these pieces of the puzzle fall into place. So that’s sort of how I came across that job guarantee.

And then you then begin to read into the literature more broadly and you understand that employment, isn’t just for income. There’s also other attributes to employment. It’s a sense of self identity, its a standing in the community. And from my own personal story, that made sense. You identify what it is you do, as, intrinsic to your own sense of self and your own well-being. One of the first things you’ve asked someone when you meet them is what do you do? And what do you do for work?

Grumbine (15:45):

So, Jengis, in understanding MMT, you know, we oftentimes hear people say things like “taxes, don’t fund spending”, and then you get the people that are, you know, into the weeds. They start dissecting the word “fund” and they start dissecting the nuances of what you’ve stated. And there’s all sorts of conversations, picking apart words and picking apart the way we phrase things, and people that haven’t heard of MMT are still trapped in what I would call the old way of thinking.

As you bring these things to them, a lot of the stuff sounds absolutely absurd. People are so conditioned to believe that countries are broke, that they can’t do nice things, that they can’t provide a job guarantee, that they can’t do those sorts of things. And as you gave the money story there that Warren Mosler has told or Mat Forstater, basically that is the MMT story. Bill Mitchell has told that story.

The question I have for you as an activist, as someone that is basically learning this for your own purposes and also trying to take it and educate others. What have been some of your experiences with people, as you tell these stories, do you find them starting from a point of acceptance or do you see them initially reject your claims? What does that struggle look like? How does presenting the message change through the process?

Osman (17:14):

It’s a really interesting question and I want to divide it into two sections. When I asked friends those questions or enter into conversations, when they’re in those precarious sort of employment and living arrangements, they grasp it a lot more easier because they can apply it to their own situation. But I can remember speaking to family members around it saying, well, hang on taxes, don’t fund government expenditure that concept, of a household analogy doesn’t apply.

If you issue a currency, it’s more akin to a scoreboard and a referee marking up the points on a scoreboard. At the end of the day, those numbers are a statistical artifact, but it shouldn’t be something where we’re setting out to achieve. You. Shouldn’t go out and try and achieve a certain budget outcome or a certain debt to GDP ratio because without a context, those numbers don’t make any sense. So you want to focus on real outcomes. And to me, that should be employment opportunities, that should be tackling climate change, investing in renewables.

That should be creating the sorts of communities that you’d like to be. So people that were initially skeptical and would call you crazy and would tell me things like this style of thinking is holding you back. I think just couldn’t quite break through those analogies that you’re fed every day. When you turn on the news, you’re always fed that a government is revenue constrained.

There’s a budget black hole. We need to find more money. We can’t afford to give you these public services, even though we would like to. And you realize that it’s this myth that they use to hide behind their own ideology. But when you talk to someone in a more precarious situation, and I say, well hang on, money itself isn’t a scarcity, it’s a social construct. And it’s governed by the laws that we create. It’s silly to think of it as being limited.

What’s limited is what’s real and you yourself are real. Our society can always find something for you to do. And that’s why I think I like this idea of a job guarantee. I like listening to Victor Quirk, he is one of the academics here in Australia at the center of full employment and equity. And the way he described the job guarantee is this transitional arrangement, where it’s also set up along a skills development framework.

Or if you’re unemployed, you can walk into a job guarantee office, and you can say, well, these are my interests, and I’m a musician as well. I would have loved to have been able to go into a job guarantee opp and say, well, this is my interest. I like playing music. What do you have for me? And you would have these job guaranteed jobs that could take down that.

Well, here’s one in art section and it’s playing music and here are some other musicians, so you can create something with them. And as part of that, you might be required to organize a community festival and help out with that. Or you might be required to teach about band dynamics in school. It’s an opportunity to have people as peripatetic performance, traveling around the area to showcase what different cultures are like, in terms of their music.

There’s so much value to what could be created from a program like that. And I applied all that from understanding in the first instance, that, the way we conceive value and the way that we conceive employment and how it’s created in this pursuit of a profit, the mainstream is just nonsensical. It sort of, it tells you that you need to find money, in order to have these things that make us human.

MMT flips that whole understanding on its head. It says, well, hang on. We don’t need to find money to have these nice things that we all desire. We just have to say, this is what we want to create. And we go about creating that.

Grumbine (21:28):

You know, I have a question for you, and this is one lay person to another lay person. You know, we’re oftentimes concerned about the way we present these concepts to people. We’re worried about, there’s some within the MMT community that spend an inordinate amount of time focusing on the tone in which we deliver these messages.

But on the flip side, we’re surrounded by science that tells us that climate change is coming and that it’s already here, and that we’ve got very short amount of time to take serious major action in order to avoid these very calamitous outcomes that could really quite frankly make it so that our children and our grandchildren won’t really have an earth that is capable of sustaining life as we know it. And yet, all the while, a lot of us are acting as if we’ve got plenty of time to get through this. That this is like, just a gentlemen’s sport, that we can just sort of chit chat about.

And then in reality, so much of the issues that we face. Aren’t a matter of convincing people that we have to take action on climate change. It’s an issue of how do we explain that we can afford to take care of it and survive? It seems like as soon as we talk about climate change, everyone is all on board. And then as soon as we say, well, here’s what it’ll cost. Everyone loses their mind.

And it seems to me, like so much of what’s happening right now goes beyond just, “Oh, that’s a simple misunderstanding”, this is so deeply ingrained. These bad ideas are so deeply ingrained in every aspect of our life, from the television shows, we watched to the churches that we attend, to the, just everything, comic books, you name it, it’s embedded in every part of our lives.

How do we overcome that, within the constructs of the physics that’s driving the climate crisis that we’re facing as well as, a global depression that is bearing down on us, and it’s really going to effect people like you and myself ,who are lay people, that are just workers, that are just laborers, that are family people, and really don’t have the ability to issue our own currency to get us out of this. I mean, it’s a collaborative collective and it doesn’t seem like people are learning the lessons that we have to tell, fast enough to impact the very fast moving non negotiating physics of climate crisis. What are your thoughts on that?

Osman (24:08):

Oh, thanks. I’ve been having some success in breaking down some of those myths we hold around, what the economy is. When I talk to climate activists, you start by making a distinction between, well, hang on, the economy isn’t an abstraction that sits above us. We don’t work to serve this being and throw all our income at it. And people conceptualize that as a government surplus.

The economy is us, and if we have people that are suffering, and if we have these activities that we’re doing, mining activities and activities that contribute to fossil fuel, when the economy isn’t serving its function and most environmentalist agree with that, and I can conceptualize that. And then you start talking about the dynamics of how spending work.

And, at first there’s some hesitation and people go, well, you can’t just print money, and printing money’s that pejorative, and people have these images and conjectures of government going mad and printing as much money as possible and hyperinflation and Zimbabwe and Venezuela. And then you go, well, hang on, hang on, hang on, hang on, slow down.

Let’s think about how currency comes into existence in the first place. A government has to spend it. And tax liability, that’s the purpose of creating demand. So it comes after the fact, that, the currency issuer has spent, and this concept of a government borrowing its own currency, just doesn’t make sense. Imagine you issued your own currency, but you’d never have to borrow it because you issue it. So all you’re spending is new income.

You’re not limited by what you’ve previously spent and applying that to yourself and running a little household economy, conceptualizes that sort of framework. And I think most people begin to grasp that analogy. And so then you need a different analogy or different understanding for what printing money is. And in that scenario that I just described, printing money, doesn’t apply to any spending operation.

A currency issuer always spends in the same way, regardless of whether it’s deficit spent or surplus spent in the past. You’re not spending the proceeds of your tax collection. There’s an appropriation bill that passes through, in Australia its a parliament, a Congress in the United States, and there are some official in the central bank ends up marking up the size of a bank account and you’ve spent.

And so then it’s a question of is the labor available and the real resources available to implement your particular agenda. So, in the case of climate change, that shift that we need to renewables, do we have the labor skill necessary to construct that. That where I’m living in the Northern territory, the territory government is trying to frack parts of the Northern territory to extract the gas under the ground, and that has enormous consequences in terms of the water and a very dry place up here.

And so that’s incredibly risky to be fracking the water supply, but the argument is always, well, we need the revenue, but you break down those myths of how spending works. And if you can articulate that all those skills that we use in those fracking operation, so the engineers, the electrician, the laborer, that skill-set you can use in creating renewable energy, in building solar panels, in erecting windmills, and creating wave energy, we’re on the coast here, that’s a huge opportunity.

That skill-set, can still be used, but for a different purpose. And it’s not a matter of finding the money at the federal level. And it’s almost as if these institutionalized arrangements we have in place, are set up, so we can’t have those things, were set up, so it makes it appear that the federal government is limited in its expenditure. And then it limits funding to the state and the territories so they’re forced to operate under that, well, we need to find private investment, and this is what private investment wants, it wants to frack, it wants too mine the fossil fuels.

Intermission (29:16):

You are listening to Macro N Cheese, a podcast brought to you by Real Progressives, a nonprofit organization dedicated to teaching the masses about MMT or Modern Monetary Theory. Please help our efforts and become a monthly donor at PayPal or Patreon, like and follow our pages on Facebook and YouTube, and follow us on Periscope, Twitter, and Instagram [Music].

Grumbine (30:05):

And ultimately, what it ends up doing is, it convinces everyone that it is the God and savior of us all, by propping itself up as the answer to every question. And it’s the same in the US as well. I guess my question to you is this, we’ve all probably had some success in bringing about people from not understanding economics, to at least a basic understanding of economics.

That said, there are so many things that play against us, from the private sector to these parasitic industries that feed off of, the labor of people while simultaneously impoverishing them, and destroying the planet. And at the same time, the news media and every aspect of our lives is still completely telling us a lie, an outright lie.

There was a study in the UK a few years back, and it showed how austerity is social murder. And they talked about 120,000 people had died as a direct result of social murder. Many were suicides, many of them were deaths of despair, but many of them also came about as a fact of governments perpetrating this lie. And if 120,000 deaths based on austerity, wasn’t enough to get people’s attention.

And the fact that like in the United States, we have this major movement right now, where people are starting to take notice of the plight of minorities, through black lives matter, and the death of George Floyd, but even still, it’s a small microcosm while we’re in the midst of lock-down. And we’re starting to come out of this closed economy, the bread and circuses of sports and other things have largely been not around to keep us distracted.

So people have been able to pay attention, that said, as we go forward and things start reopening, people go back into daily life and they start forgetting about it. How do we make the case that this is that important? Because it oftentimes sounds to me, like people try to approach this from the purely wonkish academia type approach, when in reality, you see people when you walk through cities and they’re laying under park benches with cardboard boxes on them, in newspapers, covering them, they have no healthcare and their teeth are rotting out of their mouth.

And you look at them and you just keep walking because it’s so normal, but it’s not normal. There’s nothing natural or normal about it. How do we make these things stop being so blasé, when in fact, every bit of this is a political choice, there’s no economic financial reason why any of this has to happen. And yet people are not tying them together, fast enough, to stave off these cataclysmic events.

This drives me mad, as a guy that interviews a great many experts on the subject, and who is an activist myself. I am left sleepless many nights pondering, how do we make this happen? How do we change this? And I’m just curious, Australia is a world away, but it’s still the same planet.

Osman (33:34):

That’s a really interesting question. And, when I moved to the Northern territory three and a half years ago, that’s one of the first things I noticed was the difference between a black community and a white community. So, I always had this theoretical understanding of indigenous disadvantage, but I’d never seen it with my own eyes.

I grew up in Sydney in a big city, and you saw homeless people and they were at the train stations. And, and when I drove up to the Northern territory and throughout parts of North Queensland and Darwin itself, it’s so much more noticeable. I sat back and I went, wow, this is such a contrast, and it was a particular group of people. It wasn’t just the white homeless guy with these newspapers, sleeping on a bench. They were indigenous people. And they have like all colonized countries, this terrible, terrible history of oppression and abuse.

And, it’s something that still sticks in my mind, how it’s almost as if that had sort of blended into the background, and you spoke about homelessness, and you’d say all this homelessness in the street and look around and Darwin is this small city, but it’s quite sparse, there’s not a lot of people that live here, and you would walk around and you’d say, well, look, there’s an empty house, and there’s another empty house.

And I can walk through the city and you can say all these apartments and you can go, or there was no one living in that one. There’s no one living in that one. I’m sure there’s no one living in that one because there’s nothing on the balconies. And it doesn’t make sense that I can see, literally, all these homeless people and I can see, all of these empty apartments right in the city.

And there’s something that we’re not quite grasping as a society. When you can physically see these two things, I’m saying, well, hang on, I can just put these together and you can take someone off the street. And I think there’s this question of marrying this back to that MMT understanding what sort of ask, what is the economic system for? And I can remember reading Stuart Chase, who was this US economist, and he titled a book called A New Deal, which is what FDR named his program off.

Stuart Chase asked that question. What is the economic system for? What is it primarily supposed to achieve? Is it for profit and power, or is it to try and provide some sort of social function to provide food, provide shelter, to provide everyone with clothing. And then you start to get into those questions about, well, what is it that we need to be doing to achieve those outcomes?

And then you have a look at lots of those non-government organizations and those health organizations and those social organizations. And you travel out into indigenous communities here in the Northern territory. And there’s a huge shortfalls in housing. Often there can be 10 families living in one house, it’s insane.

Grumbine (36:51):

Oh my goodness.

Osman (36:53):

And even the concept of housing for those indigenous communities, that concept of family is different. It’s not a mom and a dad and children or two parents and children. It’s a much larger extended family. And so this concept of half with a living area and a kitchen and two or three bedrooms doesn’t fit into their culture and the way that they live.

Though, I think you need different conceptions of what housing should be. But leaving that aside, the huge shortfall in these communities around housing and the fact that, because of so many people living in there, and because there’s so many are unemployed and are often reliant on their unemployment benefit, and then they’re put under these pernicious, sort of, regimes where they’re required to look for work, and these places are smack bang out in the middle of nowhere.

Literally I need a four wheel drive and have to drive eight hours to get to some of these communities, or you need to fly in and charter a flight. You think, how is it that we can impose the ridiculous set of criteria, in order to give someone this below subsistence living where, food is astronomically expensive, because there’s no public infrastructure to provide them with food.

You’re literally sometimes paying, I walked into one shop and there was a chocolate cake and it was $80. And you go, wow, it’s insane. It’s a third world country honestly, and it’s shameful to go out and visit these communities and to say what it is that we have created. And you think to yourself, a) you’re creating these chaotic environment by not providing the appropriate type of accommodation for everyone, or even trying to identify the type, or what does that appropriate accommodation look like?

You’re cramming masses of people into a house, and that creates its own social issues. And lots of those places are then destroyed and vandalized because of the unemployment that you then impose on them. And it just brought me back to Pavlina’s work, and thinking, well, what would a job guarantee look like out in these remote areas that literally have no infrastructure.

Grumbine (39:15):

Interesting.

Osman (39:15):

And you start thinking about, well, what does, and this isn’t for me to decide, I think it’s up to that indigenous population and those communities, to think, well, what is our cultural knowledge and what is it that way bring that’s a value to our own communities and how can we encourage the dream time learning?

I have dream time stories for creation and they have different art and different dances and stories that they tell. And they often have what they call “walk about”, so different times of the year, they go and they live in different places and they have stories for finding different watering holes and things like that. So it really then starts to re-conceptualize what employment is.

And I can remember reading Pavlina’s work on the Jefes program in Argentina, and they started to re-conceptualize what employment was for those smaller communities. And I found it really interesting that the females that were in that program, weren’t there, just for an income that sort of came as a secondary choice.

They were there for A) a social aspect, and B) to learn these new skills, whether it was baking or able to create clothing that was all these different cultural things that were embedded within them. And they would use it as learning new skills and a sense of self. I can remember my grandmother, she would sit around with all the other old women and they’d crochet and have a talk, about whatever it is, old women, old ladies talk about, but I don’t know,

Grumbine (40:59):

My demographic got missed on that one.

Osman (41:02):

Yeah, mine too. And I’d stick my head in and say hello, and they’d be like, “you’re, so and so’s grandson” and pinch your cheek and give you a chocolate.

Grumbine (41:10):

[Laughter]

Osman (41:14):

I’d get excited, because I got a chocolate, but they’d sit there, and they’d crochet or they’d prepare food. Yeah. There was all sorts of different vegetables like that. I can remember they’d pick broad beans and they’d peel the broad beans and gossip.

And then I was reading that paper from Pavlina about the women in Argentina, and it was that same concept, but they turned that into employment. And they said, well, this is what it is you do. And this is how you interact with each other, and these activities bring value to your families. That’s the way that your family is, in my nanna’s case, it was something they provide to eat to their families. That’s something of value.

So we should reward that. And then, you use some divergent thinking there, and you apply that concept to these indigenous communities and you think, well, hang on, these people have a culture as well. And they have different customs and practices that bring a sense of self identity and an understanding to those communities. And they have these stories that they tell that bring an understanding to the way that they live.

So why shouldn’t we be creating employment around that and rewarding that effort. And it’s a way I think, to bring together that monetary based and non-monetary based society, because before this country was colonized, you have a very, how do I word this? These people had an abundance of everything. They had an abundance of food. They had running water. They had kinship systems at work for tens of thousands of years, 60,000 years, if not longer.

And we came in and we impose these different structures, and we use them and we often quarantine their income when you put them into slavery, and you broke those kinship systems and you took them away from their families. And lots of the schools that I visit in my work are old missions, where you would take children from their families.

And you would say, well, this is where you live now and smack bang in the middle of nowhere. Or there could be children taken from as far away as New South Wales that were then brought up to places in the Northern territory and taken away from their families, which was a different language as well because they had, I think that was something like 500 languages in Australia.

Grumbine (43:47):

Oh my goodness.

Osman (43:48):

And you destroyed all that. And you impose this system of, well, you need to work to earn a living. And this is what we define work as, and then you use these really terrible institutionalized arrangements that then quarantine their income and effectively made them slaves. You’d learn about all that history. And you look at the state of these communities, and yes, this is disastrous.

And we talk about how disastrous it is. And we’ve had decades of what they call trying to close the gap, and the situation has gotten worse. And you think, why is it that no, one’s talking the fact that there’s these completely and utterly different societies and there’s a monetary based society and a non-monetary based society.

And how do we look at trying to marry that? And how do we look at trying to value that indigenous contemporary knowledge? So I think that’s one area to be explored. And then I got thinking about the job guarantee and thinking, well, how can you use that as a mechanism to take that indigenous knowledge and use it as a vehicle for that?

Grumbine (45:06):

You know, it’s interesting because right before and during Bernie Sanders first run here in the United States, when he was running for president, the first go round, the Dakota access pipeline was being put in, over indigenous communities land, burial sites, ancestral sites, through their water supply.

And a lot of people that had never experienced indigenous culture or had never really done anything on the scale of activism, like being at those camps and trying to block that pipeline, they got to experience life within the reservation and they got to experience a whole different way of being. And many of the people that went there, having been through the capitalist society outside of that, and having lived in a cooperative society within that and watching the very different way people respected one another, the way that they talk to one another, things they valued, the spiritual connections, etc.

Many of them never wanted to leave. Many of them were like, wow, people talk so negatively about this stuff because they don’t understand it. But if they ever got to experience the comradery and the bonding and that spiritual connection that occurred, they wouldn’t want to leave either. And I think oftentimes as a white man and the majority of the United States, we oftentimes think of ourselves through our own lens, which is a very structured Judeo Christian waspy European type, thinking with the whole concept of Calvinism and working hard and lazy people and judgment and so forth.

These other groups didn’t have that kind of thing, they were very cooperative. And I really sometimes wonder if we can ever break that cycle, and go back to the primitive, so to speak, but it just makes you think that we’ve been so conditioned to believe this is the one right way, things that you’re saying in particular, with the indigenous folks out there and the non-monetary way of life that they had and finding ways to blend that.

I think that is so rich and valuable because I really do believe we come at things, we complain about our governments using the, “there is no alternative” approach, but in reality, when we look around and we get past our own dominant position and we start looking at the way things were done or are done in other communities, there is something to be learned there. I think that’s a really great insight you had that, how do we merge these two concepts with this monetary economy and this job guarantee approach, and quite frankly, groups that are not living in a monetary based economy, they’re living in a more cooperative society, a more cooperative approach to life. I think it’s worth exploring.

Osman (48:15):

And it’s fascinating. I found it really interesting. And especially when you go out to these communities, and you always observe, and you begin to understand those cultures and you start to break down your lens and your understanding of the world. And then, I tie it back to my own ancestry, where, my grandparents are from Cyprus, and they migrated to Australia in 1970, but my father tells me that it was a very subsistence type of living.

They were in this remote village and they were farmers and they had no electricity. My nanna tells me that around the time my father was born, they had a running water. And so she was stoked. She didn’t have to go to the well to get water anymore. And they had goats. And so they would milk the goats. And the women in the village would take turns from week to week and making the cheese.

And they all lived on this side of the mountain and you had a much more communal way of life. And so these concepts of employment and unemployment in the 1950s were new to them. Um, my granddad started to work for, I think they were American mining company and I’m not even too sure what they’re mining, but to this day, he still receives a pension from an American company in the mail, but they had this liability imposed on them. I think, probably around the beginning of the thirties, it started, because I remember stories of hearing my great grandfather needing to go to work now.

But before that, whenever the village was established, that concept of employment was very loose and it was a subsistence living. And you begin to think, well, how is it that these people survive without going to work for someone? And they have these different structures for creating, I suppose, their wealth and their own well-being, and into the 1950s, with the war, and became harder and harder to live. You were forced to change your lifestyle.

Not only as a result of the war, but also as a result of these corporations coming in and beginning to extract minerals and things from the land and then taxes needing to be paid, then needing to sell your labor. When your options are either to work for the military or to work for a corporation, you have to choose one. And I think that’s a situation my grandfather was in, in the fifties. You have to choose between one or another evil.

Grumbine (50:57):

Die by the gun or die by the clock.

Osman (50:59):

Yeah. But that allowed me to conceptualize. Well, I think just hearing those stories and then reading about MMT, what happened in those villages and then applying that same sort of thinking to indigenous society. It begins to make so much sense. You went in there and you impose these liabilities on people and it was this coercive tactic.

And you began to say, well, this is what you need to do in order to survive. You’ve been living for thousands of years fine, but we’re changing all that now. We can conceptualize that differently. We can say, well, hang on, this is how you’re living, and this is your culture, how do we reward this? And how do we account for the value it is you produce? Because ultimately I think currency is just a measure of value.

Grumbine (51:57):

Yes.

Osman (51:57):

I like that analogy, the same way that kilometres or miles measures distance, you can’t run out of that unit of a account, but you can run out of distance. You can run out of real goods and real resources and labor. You can’t run out of that unit of account. And then you ask yourself these questions around value, and then, well, what is value?

Well it’s not profit, because we’re told, hang on, we need profits in a capitalist society, so we can fund these services that are good for everyone, but we can’t have too much of them. And some things we have to leave to the private sector, because then we’re not able to afford these public services. And then you begin to understand that, well, hang on, that’s a load of crap.

Grumbine (52:44):

[Laughter] the false idea of crowding out, right?

Osman (52:51):

Yeah, that’s right. You need the currency in the first place before you’re able to tack, and so provided that we have those skills and those resources to create hospitals and to build schools. And we can always do that. But I think the challenge lies in re conceptualizing. What is education? Why are we going to school and learning these sort of industrialized models of education?

And this is your mathematics, this is your science, this is your English. I just think about experiences of my own educational process, and even going through university, and hating it. It was atrocious that was, you must be here at this time and, here’s all your readings and there’s too much for you to do. So it’s impossible for you to read it, even if you were to dedicate full time…

Grumbine (53:44):

Exactly.

Osman (53:48):

…yourself, full time to try and read it. And on top of that, you have to try and find work, and then you find work. And then you have to work 20 or 25 hours a week to survive. And then you have to find somewhere to live.

And then you’ve got all those responsibilities of trying to keep yourself alive, and you don’t have enough income to feed yourself and you’re just scraping by. And then you’re expected to read all this material, that I don’t think I could read, even if I dedicated myself full time to it, and had someone to help me with all those domestic tasks that you have to do.

Grumbine (54:23):

Alright. So let me ask you this, because we’re getting near the time here, near the end, I want to ask you a question. If you were talking to someone that had never heard of Modern Monetary Theory, and you wanted to give them some encouragement to dig in and learn, what would be your message of hope to them? How would you lead that conversation?

Osman (54:48):

I think I would want to go away leaving an impression that it’s never a financial constraint for a currency issuer, it’s the real resources that are the limit. If we have the labor skill and if we have the raw materials, we can always organize them in a way ,that achieve some sort of public purpose. And I always tie it back to my life as a musician.

And if you’ve ever go to a folk festival, I love the way that they’re organized. There’s all these musical acts. There’s places you can go and eat with all these different foods. And it’s a very fun and vibrant atmosphere. And there’s people that play music all through the evening up until the sunrises. And I think we have that skill set and we can create our communities to work in the same way.

I could go to work doing something that I love doing. And I quite like doing what I’m doing now, in terms of organizing people and fighting for better working conditions. But I would love to see my friends to be able to achieve that same goal. So if they’re musicians, it would be great to have programs, where they can wake up and go to work every day and they can teach people about the dynamics and music.

They can tutor people in music tuition. They can organize festivals within the community that allows other people to enjoy the fruits of their labor. You could have people painting murals on public buildings. You could have people engaging in what we would consider volunteer work now, things like community gardens, this huge scope for rehabilitation work in terms of flora.

There’s so many places in Darwin. I look around and think, wow, that could do with some work to be restored to how it would have looked, before we started to build cities, and you could have all these beautiful parks, and in those parks you could have all these wonderful things, and festivals and artworks and sculptures, and really your imagination is the limit to what it is you’ve wanted to create.

Grumbine (57:12):

I absolutely love that, for me is a great way to close this out. The idea that everybody brings to the table, what matters to them and that discussion can go any way you want it to go. MMT doesn’t dictate anything. It’s simply gives us a lens to understand, and to realize that we’re not constrained by pieces of paper or coin, we are constrained by not only our imagination, but the real resources available to us. So I think you make a very compelling case. And I gotta tell you, I’m really grateful to have you as a friend Jengis.

Osman (57:50):

Thank you.

Grumbine (57:50):

Just a good and decent man. And I count myself blessed to have you in my life. And I really appreciate you taking the time to do this with us because these podcasts I hope will serve to change society. I hope that these stories like such as the ones you’ve told tonight will really help people start dreaming a better dream. And maybe we stand a chance if people start thinking that way. But I want to thank you very much.

Osman (58:18):

Yeah. Thank you so much for having me. I feel so incredibly fortunate to be able to share that story. And for people often ask me questions about Modern Monetary Theory and even extending beyond that. They’ll say “What do you think your community should look like?”, and I think that in some ways as a lay person, I can demonstrate that.

Well, hang on, I’m not an academic, I’ve been through precarious employment, and I’ve gone through all these things that everyone else has, but it is possible to sort of break down these myths that we hold and, put it, start articulating what it is you want your community to look like, and how it is we can do that.

Grumbine (59:00):

I think that’s powerful. Though, with that Jengis, I want to thank you again.

Grumbine (59:03):

Folks. My name is Steve Grumbine. This is Jengis Osman. And I want to say thank you so much for being with us. We’ll talk to you soon. Have a great week, bye bye.

Osman (59:15):

Thank you so much. Bye.

Announcer [music] (59:21):

Macro N Cheese is produced by Andy Kennedy, descriptive writing by Virginia Cotts and promotional artwork by Mindy Donham. Macro N Cheese is publicly funded by Real Progressives Patreon account. If you would like to donate to Macro N Cheese, please visit patreon.com/realprogressives. [music]