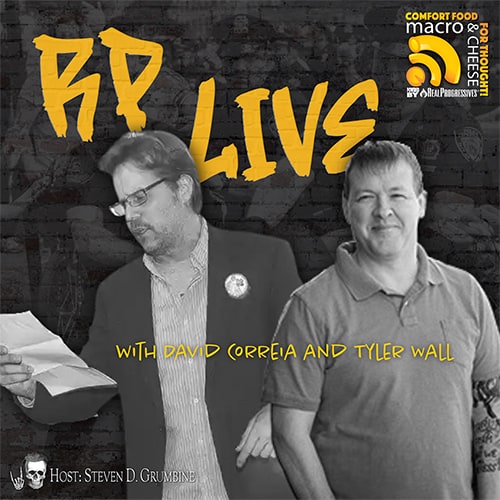

Episode 231 – RP Live with David Correia and Tyler Wall

FOLLOW THE SHOW

David Correia and Tyler Wall, co-authors of Police: A Field Guide, lead a webinar where they answer questions and dispel common myths and misunderstanding of the role of police.

In this episode, David Correia and Tyler Wall, co-authors of Police: A Field Guide, lead a webinar about policing in the US.

The common narrative about the police is intentionally misleading. Without a class analysis and an understanding of history, it will remain a problem with no solution. Policing isn’t a side-show to capitalist political economy. It’s part of the main stage. Far from engaging in enforcing the law and fighting crime, the police are a coercive force, with origins as slave patrols, colonial militia, and strike-breakers.

Addressing possibilities of reform or abolition, the point is made that attempts at reform only serve to further maintain the legitimacy of the police. Reform does not address the monopoly on violence — a violence that is non-negotiable and non-reciprocal. Reform feeds into the myth that we hold the police accountable. Abolition, on the other hand, does not mean absence; it looks at possibilities for a different kind of world. Can this be done within the capitalist system?

David Correia is a professor of American studies at the University of New Mexico. He writes about violence, law, and race under capitalism.

Tyler Wall is an associate professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. His areas of interest include critical police studies; state violence and racial capitalism; law & society, race and class.

Correia and Wall are co-authors of Police: A Field Guide (Verso)

Macro N Cheese – Episode 231

RP Live with David Corriea and Tyler Wall

July 1, 2023

[00:00:00] David Correia [Intro/Music]: Most white people in this country live in a world that, for all intents and purposes, doesn’t include police. They don’t see police. Police don’t show up at their house. They don’t ever really have to call police. They’re not tailed by police or pulled over by police. For them, police is not a problem.

They have the kinder, gentler version of police.

[00:00:26] Tyler Wall [Intro/Music]: Capital requires this autonomous state power that’s not meant to be accountable. And this goes directly in the face of so much common sense, views of civil liberties, the liberal ideology about a liberal democracy.

[00:01:35] Geoff Ginter [Intro/Music]: Now, let’s see if we can avoid the apocalypse altogether. Here’s another episode of Macro N Cheese with your host, Steve Grumbine.

[00:01:43] Steve Grumbine: Hey folks. This is Steve with Macro N Cheese. You might already know that Real Progressives has an informal webinar series called RP Live. It gives our volunteers direct access to all kinds of interesting experts. We like to turn some of these webinars into podcast episodes for those who prefer to get their information this way.

This week’s podcast is from a recent RP Live with David Correia and Tyler Wall, the co-authors of Police: A Field Guide. We did an interview with David about a month ago, and I don’t know about the rest of you, but I learned an enormous amount about the history and the role of the police in our society.

It’s mind-blowing. Now, you get to hear the two of them together.

[00:02:26] Virginia Cotts: Good evening everyone. Welcome to RP Live. Enjoy the evening everyone. Commie John. Go ahead.

[00:02:34] John Siener: Thank you, Momrade, you’re looking lovely as always, and thanks everyone for coming and joining us again. This is gonna be a really good one. So if you haven’t heard the Macro N Cheese podcast we did with David Correia recently, it’s amazing. And his book, I haven’t read it yet, but it’s in the mail. Check out our Macro N Cheese podcast every Saturday morning, 8:00 AM Eastern.

You can listen to it at our website or Spotify or anywhere you listen to your podcasts. And Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, Steve Grumbine does The Rogue Scholar. It’s a little live stream at noon Eastern. And also visit our website, realprogressives.org as we are republishing the entire archives of New Economic Perspectives, and that’s a pretty big deal. And always feel free to donate to us at patreon.com/real progressives. We run solely on your donations to bring you this cool content. And our social medias and all that stuff. I’m gonna let these guys introduce themselves and give their bios and a little background and do their thing, and then we’ll do some Q&A.

So the floor is yours, gentlemen.

[00:03:46] David Correia: Thanks. We’re thinking about making our comments brief so we can make this more of a conversation, so easily less than 30 minutes. My name is David Correia, I’m a professor at the University of New Mexico in the Department of American Studies. Tyler and I co-wrote Police: A Field Guide, which came out in 2018 with Verso, a revised edition was published last year.

It’s an interesting book, in that, the field guide concept is not a gimmick, it’s really like a series of entries, terms and concepts, and things about police. From the perspective of police. We wanna understand the police view of the world, so that we understand what it is we’re up against. I’ve written other things, you can find me on websites that lists stuff like that.

[00:04:35] Tyler Wall: My name’s Tyler Wall, I’m an associate professor in sociology at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. I write on policing, I’m a critic of police, that’s kind of the main thing that I write on. David and I did the Verso book Police: A Field Guide, in 2018, like he said, but we also did, in 2021, an edited book with Haymarket books called, Violent Order: Essays on the Nature of Police.

So I’d recommend everybody take a look at that. There’s a lot of other authors in that, that write on the links between the environmental movements, and policing, and the television show, Dexter. So there’s all kinds of stuff in there.

[00:05:16] Correia: The title of this is Reform or Abolition, and if that’s a question, then the answer is abolition, and we’re done. Let’s call it a night. But we’ll flesh it out a little bit more. I thought what would be useful, since no one really takes police seriously, even criminologists don’t take cops seriously.

Criminologists, even if the code didn’t take them seriously. But even criminologists don’t really take cops seriously, they think of them as public servants, or functionaries or bureaucrats. If they fuck up, then we just have to change some policies and some laws and fix it, and that’s not taking cops seriously. Tyler and I are interested in taking police and policing seriously.

If we’re gonna do that, we have to start by understanding, by putting police as we know it, in historical context. So I wanna do that briefly, then Tyler’s gonna expand on that a little bit, say a few things about reform as we know it today, as it’s practiced in this country, and in other settler societies or Western countries.

And then that’s all we’re gonna do, and then we’ll leave it open for Q&A. So let’s talk a little bit about the history of police as we know it. If you saw the podcast that I did with Steve, I talked a little bit about that. I just finished the book with Haymarket, on the 1902 anthracite coal strike, which my argument in the book is, this moment, this 1902, is a moment where police, as we know it, are born.

And so I wanna talk a little bit more about that, particularly the period prior to 1902, as a segue into talking about this question. Well, what is police? When we talk about police, what are we talking about? So, one of the common claims that, particularly liberals, progressives, make about police, is the importance of public and professional police, as though this is a common sense notion about what democratic policing would look like. And one of the reasons why they can get away with this, is because there’s not a lot of good out there. There aren’t any good histories of police really. There’s some targeted ones, Stuart Schrader’s got a good book that charts the internationalization of policing and this cross border relationships among, basically the way that the United States like exported policing, and then imported a version of counterinsurgency policing back to the United States. There’s some others, but usually even people on the left, when they reference histories of police, it’s almost without citation. Police were the slave patrol, police were the colonial militia. And while that might be true in a broad sweep, I think it’s important to look really specifically at what we’re talking about when we say like, police come out of the slave patrol, the police we have today come out of colonial militias. There’s often very little effort in those stories, that talk about class, or the role of police in building the infrastructure for a capitalist society, a capitalist economy. And lemme just do that briefly, and Tyler, go ahead and like totally interrupt me.

You’re doodling, I hope you’re taking notes and not like…

[00:08:17] Wall: Taking notes

[00:08:18] Correia: This is the webinar, Tyler.

[00:08:20] Wall: right I know.

[00:08:21] Correia: When I was working on this book that I just completed, it was fascinating to really read a lot of these mid 19th century discussions, debates, going on about political economy. Because as probably maybe most of the listeners who are watching this know, the settling of this country was a commercial enterprise.

The Commonwealth, in Pennsylvania, was a commercial enterprise. So the job of the state was just to charter corporations that would extend and enhance commercial enterprise. But not just a commercial enterprise, also a political project, largely. And so it made sense, in that context, in the late 1700’s, early 1800’s context, in which policing, or the coercive capacity to enforce property relations that were necessary for that commercial expansion, to create private sector policing.

As I pointed out in the podcast, you name the industry and they had their own policing. Railroad Police, Steamboat Police, Coal Police, Merchant Police, eater police, goes on and on. And this was, until the progressive era, really just after the strike of 1902 in Eastern Pennsylvania, this was taken for granted.

This was the only way it could be done. It made the most sense, because of course, these commercial enterprises are private enterprises, and so it was up to them to defend their own commercial interests. And it isn’t until after 1902 that the shifts, the pressure, during these early progressive era reforms, focusing on the idea that somehow all of the problems of policing, and the problems at the time, by the way, weren’t that cops were killing people, even though they were, the problem was that, the killing of people produced economic instability. It interrupted stable industrial production.

And that was the problem. That was the problem that progressive era reformers identified with police. That the violence of police eroded public support for police, and therefore the solution would be creating a public police.

When we talk about reform later, one of the things we’re gonna talk about is the way in which most abolitionist criticisms of police, or calls for abolition, are deemed naive or dismissed as juvenile. As though police, this is another way in which people don’t take police seriously, as though police were just given to us from on high. But police, as we know it, was constructed. It was a political accomplishment. It wasn’t haphazard, it wasn’t ad hoc, it was carefully constructed, it was built.

And so when we talk about abolition, we’re talking about building a world beyond police. The police we have, just like the police that we have now, were carefully constructed.

After the strike of 1902, that I talked about in the podcast, there was this ‘all hands on deck’ effort, a propaganda effort, to build this idea for a new police, that need for new police. Legislative efforts that were linked, and I read about this in the book, all these states, purely East coast states, linking their efforts, sharing legislative language to produce very specific kinds of public police, funded in very specific ways, to produce specific outcomes.

So, and all of it was really around disciplining labor. It was entirely around disciplining labor. The idea of strikes, as being disruptive, and particularly coal strikes, because of course, coal provided the fuel for every other industry. So labor had to be disciplined. The only way to do that was through police.

The argument of early labor leaders, particularly United Mine Workers leaders, were, ‘no, we’ll, discipline labor, we don’t need your cops to do it, we’ll do it.’ They basically promised to be labor’s police, and in a lot of cases, behave that way too. So the police we have, if we can’t draw a straight line from the slave patrol and the colonial militia to the police we have, I think we can draw a straight line from the transformative and disruptive strikes of the early 20th century period, to the coal strikes, that really called into question a particular kind of order.

And it was an order based on total control of capital, that dictated the terms and conditions of labor, and when labor was strong enough to oppose it, that order broke down. And a new kind of mechanism to control labor, to produce a stable industrial order was required. And my argument is, this is the birth of police as we know it.

And the reason I make that argument, I’m gonna throw it to Tyler now, is because when we talk about police, we’re talking about ‘order’. When Tyler and I talk about police, we’re not only talking about cops in uniform, we’re talking about the logic of coercive authority required to fabricate and sustain a particular order.

And that’s an order of capital and private property. You don’t have cops, you don’t have private property, as we make the point in the book. I think clearly, if you’re gonna have a system built on exclusion, someone’s gotta guarantee that exclusion, and that’s cops. And in order to talk about reform and abolition, I think we really need to understand what we’re talking about.

So, police, as we know it, is a constructed political project. And the role of reform in that project, is to basically resolve the contradictions inherent to the violence of police in sustaining that order. But now that we have this just brief, like, history of police, and these broad strokes, we should shift very specifically and talk about, what is ‘police’ when we talk about it. Because Tyler and I talk about it more broadly than just cops in uniforms.

So Tyler,

[00:14:08] Wall: Yeah, to jump off what David just said, one thing that I would clarify is, I think what he’s saying too is that, policing doesn’t just reproduce an already existing order, as if there’s some order separate from police, but he used the word fabricate, which is one of our colleagues, Mark Neocleous, wrote a great book on this, called The Fabrication of Social Order on Policing, but that the police actually, actively, fabricate an order.

They help produce the order of capital. It’s not just that there’s capital, and it exists. Police come in and kind of help reproduce it. The police are producers of the order. They help actually fabricate it, which is another way that I often explain this to people is that, if you accept that, then that means policing isn’t a side-show, to capitalist political economy, that actually, it’s part of the main stage, it’s part of it. That capital kind of requires this particular coercive capacity concentrated in a police apparatus, to kind of help actually, actively, produce an order of private property, that it’s hard to even imagine that order without having some type of special power, to be able to help actively produce an order. This is kind of going to what David kind of alluded to, but I often ask people, what is police? Because it’s a simple question, on the surface, but then it gets more complicated the more we dig into it. And it’s also a good way of then pushing back, I guess, on kind of commonsensical myths. So we often hear police being conflated with law enforcement, crime fighting, things like that, right? There’s the narrowing of the police function into these activities.

Even though, empirically speaking, we’ve known forever, essentially, police do very little enforcing of the law. This is well established by sociological criminological research for a long, long time. And they do very little, real, what we would think of as, ‘crime fighting’.

I don’t know the most current numbers, but a decade ago it was like, the average cop in the United States makes a felony arrest once every four months, and most police don’t ever pull out their firearm during their career. So it’s not law enforcement, it’s not crime fighting, it is about this fabrication of order. And this leads the questions about reform and abolition.

What I would say about what the question was, is police, policing, is a prerogative power. What we mean by that is, policing isn’t actually the same as law, in the standard sense. The way I’d describe it, and I’m using other people’s work here, but is to think about police as kinda like, the law’s admission, of the law’s failure, to be able to compel people to do what the law wants them to do. That policing is kind of that special force, and that means it is kind of the concentration of the state’s monopoly on violence. It is a kind of concentration of that violence. It’s a coercive capacity, as David said, and this is kind of integral to the way then capital and property has to function or operate. But by prerogative power, what we mean by that, is that it’s kind of a power that is inscribed in law, but it always exceeds it.

It’s an emergency power, an ordinary emergency. The way that I’ve described it in some of my independent work, it’s an ordinary emergency power, that with police, everything is a potential emergency. Everything is an emergency, and that becomes one of its key logics, its key justifications. It presents itself as counter-violence, to some other anarchic kind of violence always lurking. But also, in terms of violence,, in this concentration of monopoly of state violence, the violence is built into it.

And that doesn’t mean violence in the sense of hitting someone on the head with a nightstick all the time. It means that the threat of violence is inherently built into police. That is what makes police, kind of a unique special power, compared to other institutions. And it’s in generalized capacity, meaning, the private security guard is definitely part of a police power, but their power of coercion is very limited to the Target, or to Walmart, or whatever that private entity is, where the policing is kind of the broad, generalized coercive capacity of the state.

You leave one jurisdiction, you go right into another jurisdiction of policing. But the violence of police, which is always fabricating this order of capital, it’s also non-negotiable and non-reciprocal. Meaning it is, I would say, despotic, in a certain way. Meaning the law recognizes no real legitimate resistance to policing, by and large. You can always find specific examples, this and that, but the law doesn’t really recognize, you have no choice, it’s non-negotiable, it’s non-reciprocal. One of my favorite formulations is from another author, Evan Calder Williams, where he talks about police. There’s no such thing as an equal exchange between a cop and a subject, meaning there’s no equal exchange, it’s fundamentally asymmetrical, and that’s built into the actual legal architecture of policing.

And so what this means then, and hopefully I’m being clear here, but if not we can clarify in Q&A, when I said it’s a prerogative power, meaning the standard liberal account that we have of policing in a liberal democracy, is that the law holds police accountable. The idea that law trumps the police, and in fact, in the so-called global North, we often judge entire nations based on them being a police state, because the ideology behind that, is that their police trumps law. And in fact, that’s I think, one of the key mythologies of policing, in a place like the United States, that follows some kind of a liberal democratic structure. Which is the law is supposed to hold policing accountable.

It’s the rule of law that rules over policing, and policing has to be accountable to it. But if we think about policing in the way we write about it in the field guide, is that if, in fact, it’s a prerogative power that kind of exceeds law, when I said it polices the law’s admission of its own failure, that’s a way of saying that the police power is actually not meant to be accountable.

It is that special, what James Baldwin, the great American author, in his 1966 famous report from Occupied Territory, he refers to policing as an arrogant autonomy. An arrogant autonomy, because it is autonomous. And this is backed up, even by other less critical scholars, that there is an institutional autonomy through policing as an institution.

And that meaning, the key question people always ask is ‘how do you police the police’, it’s kind of an interesting thought experiment, because how do you police something that is not supposed to be policed. That it’s supposed to be removed from law, and also then, as part of the state, be above the state. The idea that the state intervenes, autonomously, it hovers over civil society, so to speak.

And so I guess that’s what I’m trying to get across here, is that we have to start from the idea that capital requires this autonomous state power, that’s not meant to be accountable. And this goes directly in the face of so much common sense views of civil liberties, the liberal ideology about a liberal democracy.

And so that means, one reason why policing is always at the center of so many struggles, one, it’s always the last resort that you see. You have to go through police in order to affect any type of change, because they’re the stop gap that prevents any type of change. And to do that, then capital and the capitalist state requires this autonomous, this arrogantly autonomous police force, in order to quote, get shit done, without necessarily waiting on the slow deliberative process of legal reasoning, or juridical, legal kind of maneuvering that things need to be done now, that’s the emergency part of it, so we need police to handle it.

And the one thing that I would say then, quickly, on law and police is that, one way to think about police and laws not being necessarily the same, is that the law tends to follow, being law comes in always retroactively after the fact. This is why I say the police is both inside the law, but outside it at the same time.

Meaning, the law gives police, cops, and the institution, basically, virtually unlimited discretionary prerogative, to decide how to handle shit. And the law then gives them that authority. Marcus Dubber, the great legal theorist, talks about police discretion, the ability to make decisions. The courts have historically refused to define discretion, because to define discretion, is to draw a line around it, is to limit it, is to limit the police power. But it’s not meant to do that, so that’s why the courts always refuse to define it. because to define police then, is to set parameters around it. And the law essentially says, you can never give a cop predetermined things they can’t do when they run into that building, because you never know what’s going to be on the other side of that building. So there’s this blank check, carte blanche power of police.

So that’s one way to think about it. And then the other way is that, the law always comes in retroactively. The law gives the police the authority to shoot someone down, and the courts only come in after the fact, to determine if that was quote ‘constitutional’ or not.

And yet, of course, the law can’t give back the mother her son, who was shot down in the street. So the law always follows the police. It gives this carte blanche power, but at the same time then, only comes in after the fact. So this is that emergency power that we’re talking about, the prerogative. So where I would wrap up my comments is to say, this is what reform is trying to do, on some level.

How do you police a power that’s not really supposed to be policed, not supposed to be held accountable, and reform then, is an effort. One, what we’re saying is that’s why policing is always at the center of these struggles, because it’s just autonomous force that gets to intervene in all kinds of circumstances.

And so reform then, becomes a certain promise of policing the police, of making it accountable, of bringing it to heel, on some level, making it follow certain kinds of rules, putting boundaries around it. And yet, what we would suggest is that reform fails at that, and that’s the key logic of policing itself.

[00:25:14] Correia: Yeah, that’s a good segue into reform. And I may just say something briefly and then we’ll get the Q&A. That’s a great way to get to reform, because the way that Tyler and I think about reform is in this context, in that, the violence of police then is necessary, to fabricate and defend the system, but that violence produces chaos and disorder, that threatens that system.

It includes in it, the contradictions that threaten to undermine it, and it is reform that resolves those contradictions. That’s the role of reform, to resolve the internal contradictions that police create through the use of their violence. Usually it’s the violence that is extraordinary, exceptional, shocking violence.

Like, in the podcast I talked about James Boyd in Albuquerque, or Mike Brown in 2014, George Floyd, that threatened to really upend that discretion, that threatened to actually impose an accountability that can’t be imposed, and that’s the role of reform. And we actually look at reform empirically. We could take examples, we could take specific cases.

The results are always about shoring up legitimacy. And the aftermath is, more cops, more weapons, and more capacity to engage in coercive activity. And that’s not our critical analysis here. Listen to cops, and particularly democratic politicians, describing the problem. And they will say, straight up, the problem is a lack of faith in police.

The problem is police community relations. The problem is not cops killing little kids. The problem is lack of faith in police because of this bad apple cop. And so we could have a conversation about types of reform, and I think there’s plenty of thinkers that abolitionists who talk about what they call non reformist reform.

If some reform robs cops of resources, robs them of weapons, robs them of personnel, then that’s not the same thing as the reformists: ‘oh, we’re gonna raise standards, we’re gonna give them more non-lethal weapons’. There are distinctions to be made, and we could talk about those if anyone wanted to. But I think we don’t see reform as some sort of external factor or force operating on police.

It’s part of the logic of police. It’s built into it. There has to be a way to resolve the contradictions that emerge from the use of violence, because if you’ve had any contact with cops, you understand what Tyler means, I think, by the arrogant authority. And if you’ve ever seen a cop use violence, it’s just as arbitrary as any other interpersonal violence. That sort of shocking violence. And that undermines the authority that capital requires cops to have.

And so there has to be some way to shore that up, to resolve that, and that’s where reform comes in. So I don’t see any difference between cops and reformists, but they’re engaging in the same project.

[00:28:18] Wall: I was just gonna add, one thing to think real quick, on reform. There’s typical reform, the standard reforms that are part of the police all the way back to the 1800s, is that there’s often controversy around police practices, and then there’s promises of doing it better. And those promises are quite predictable, and they’re broad categories, but essentially typical reforms offer more training as the solution. And that training can take a variety of different forms, anger management, how to communicate better, education. That’s built into the very logic of policing historically, which is we need more educated cops, and therefore we need to give them better education inservice or university, that will make them better police.

Technology is another one. Get maybe new technology. Why are police not doing a great job? It’s because they’re uneducated, they need more education, they need more technology, so they need more weapons, or better communications, this and that. And one thing to say about that is, often the reforms that were the promised solutions one day, tend to always end up being part of the problem, the legitimacy crisis of policing, another day.

So classic examples, I’ve written on the history of the police dog. People don’t think of the police dog as a reform, but it was historically promised as a reform. There’s a quote from a cop in the 1960s, that goes, ‘you can’t call back a bullet, but you can a dog.’ That’s a reformist logic. Instead of shooting people, we can sick a dog on them.

And of course then we know May, 1963, Birmingham, Bull Connor, and the image of the dog attacking Walter Gadsden, the black youth, then became this serious legitimacy crisis. But the police dog was a reform, even though we don’t often think of it as a reform. Dave said tear gas. Tear gas was a reform. It was a non-lethal, less lethal technology.

So it was a solution, one day. Rubber bullets that we saw really come onto the national scene for many people during the Floyd, Breonna Taylor uprisings of 2020. But rubber bullets, they were a reform, and yet they’re also then at the heart of the policing crisis today. So the promised solutions in the past, tended to always still be the problems today.

[00:30:45] Correia: Yeah, this is a question from Cheryl Van Epps. ‘How do we get working class folks to quit putting their trust into the police, authority figures, who keep doing us harm and injustice? It’s like what we’ve been so thoroughly taught, that we must respect authority, experts, leaders, is so ingrained into our heads, that we forget the police brutality and criminal acts we see on social media, on our own streets, our own experiences, so much so, we still expect to get a fair and just outcome when we call 911. How do we break the American public of this worldview?’

You wanna take that?

[00:31:19] Wall: I’ll take a stab. We obviously don’t have the answers cause if we had the answers…

[00:31:24] Correia: Yeah, if we had the answers, police would be abolished. So we don’t have any answers.

[00:31:27] Wall: Yeah, but I do think what this great question is getting at, and I think it’s something that is really hard to contend with, and to think about, and even maybe acknowledge, as people’s attachment to policing, as both the practice, but also the idea. That’s why abolition seems for many people, pie in the sky, either utopian, naive.

I think we have to think hard about the ideological, but not just concerted intentional ideological views of policing, but the fact that policing is a key element of what we think about as ‘order’ in society. So we’d even say the question of order or society, we often smuggle in the idea of policing, the idea that you have to have this policing.

And that means there’s this theory of deep commitment to ideas of policing, that I think actually influences all of us. There’s the great quote that came out in May 1968, ‘kill the cop in your head’, and the idea being, that we all had particular identifications with authority and with policing. And that is, I think, one of the fascinating things about 2020, and the uprisings, is that, there was a mass unprecedented movement that really targeted the police as key to the inequality built into our contemporary society. And there was a real questioning and probing of the police, as kind of an idea even. This was on the agenda. Now, are we there now? I think we’ve probably maybe lost some ground, in some ways, but I think that’s a tough question to get at.

But I think it’s an important question. I think historically, and the question also highlights calling the police, I think that’s the concrete practice, or the concrete question, is how we can think about the police as somebody that we call, and that’s both ideological, or it’s built into our society, but it’s infrastructural too.

You can’t even call 9 1 1 without also calling the police. You can’t have a health emergency because policing is built into that system. But I do think we have to have these conversations with people. When my kids were young enough to have babysitters, I always have a thing that I got actually from a book talk me and Dave gave, where some activists showed up, and gave me some flyers they were using to work with people in Washington, DC, had a graph saying, think twice, basically, before you call the police. And it gives a diagram to say, can you handle this problem on your own? Yes, then handle on your own. No?, Is there somebody that you know that could maybe help you do it, instead of the police?

It wasn’t saying never call the police. It was simply trying to get people to think that we can handle a lot of problems on our own, without resorting to calling the police.

[00:34:22] Correia: The only thing I would add to that, I think that’s a great question, and it’s hard sometimes to talk about this when we’re keeping two things in our head. One is the police we have, and one is what is it we’re talking about, when we talk about police. Because if we’re talking about the working class, working class folks, it’s a question of interests, and the great victory of destroying the union movement and destroying the solidarity of working people, has been to then shift their interests and align them with capital. And cops serve the interest of capital. And so if you’re interests are aligned with capital, then you’re gonna call cops. And so, working class, or anybody, sees their interests align and served by capital, then police are not somebody they’re interested in abolishing. They want more cops, they want tougher cops, they want cops with more guns. So I think the way to do that, is to build a different kind of class-based movement. I talked a little about this in the podcast. When I was talking about 1902 and the birth of police as we know it, it was just as much an accomplishment of union leaders, who were just as much subscribed to this idea of industrial stability at all costs, and if you need the cops to do it, then so be it.

And if that’s the end all be all, if that’s the highest goal, industrial stability, then we’re stuck with the cops we have. And so this idea of a union movement serving this pocketbook, if it’s just wages and working conditions, then we’re stuck with the cops we have. We have to have a broader social movement rooted in class-based analysis, I think, to really sever that tie between cops and the working class.

Here’s one from Karen Calliguri. ‘In the interview with Steve, you talked about how Americans have been trained to fear others, which leads to that mistaken belief that we need police to help protect us from criminals, bad guys, et cetera. Do you have some suggestions how Americans can organize their communities in a way that people feel safe, without feeling the need to have an authoritarian group, like the police, maintaining order?’

This gets back to what Tyler was saying about what is police. There can’t be a competing order, because that then undermines the order that police fabricate and defend. So there’s always a vacuum. A 9 1 1 has to be the only option. And so that’s why that great flowchart from those activists in DC was interesting, because it requires constructing alternatives at a neighborhood scale, at the scale of a street.

I remember 15 years ago, my sister-in-law was being harassed by this guy who lived next to her. He was just like walking into her house, scaring the hell out of her. And my mother-in-law and I, just went and confronted the guy, and we knocked on his door like, ‘you’re moving out tonight’. And we were standing there, and I was hollering at the guy, and we didn’t know the neighbors, cause it wasn’t our street, it was her street. These neighbors come over and they’re like, what’s going on here? And at first they were a little upset at us, and then I explained what happened, and they’re all like, ‘well, don’t call the cops’. No, no, we’re not calling the cops, we got this. And so the guy was moved out in two days. This is not a prescription for everyone to do, but I’m just saying that it requires taking up an awful lot of labor from police, doing an awful lot of labor and constructing it on our own.

There’s resources out there. Steve asked a question about what we could do. Interrupting Criminalization is a group that has been doing a lot of work in political education. Is their website Interruptingcriminalization.com? I think that’s right. Mariame Kaba is involved in that group.

[00:37:52] Wall: I would really recommend Mariame Kaba and Andrea Ritchie’s new book, No More Police. One of the things I would say is, and I think definitely there’s a lot more people, if you really wanna talk abolition, I think, to have on something like this that really is actively working on this, on a concrete level. But that’s what abolitionists do.

I think that’s one of the things to highlight, is to try to build alternative ways of handling problems, while still taking real interpersonal harms seriously. So abolition comes out of, largely black and brown women, grassroots organizing and activism, of trying to address certain problems within their communities, that they saw police actually making worse.

And so I’m thinking of a thing, that our friend Rachel Herzing, great abolitionist organizer, called Build the Block, trying to work with people in Oakland. George Ciccariello-Maher George Ciccariello-Maher’s subtitle of his book, World Without Police, is ‘Strong Communities Make Police Obsolete’. But the Build the Block project, as I understand it, was working within a local community of trying to cultivate a praxis of community solidarity, that could handle most of their day-to-day emergencies and problems. So what that looked like was, going to people and explaining, and trying to have conversations, political education, about why we don’t wanna necessarily want police in our neighborhoods. They tend to cause more problems, increases the chances of violence, families being separated through incarceration, someone getting arrested… and then looking to leaders within the community that had particular skills.

So there was an EMT that agreed to handle a lot of basic medical problems, instead of calling the cops and 911. And so they create phone trees and certain types of networks, in order to solve a lot of their problems. And I think this is important to keep in mind, thinking about abolition, where it’s easy to think of abolition as just, either no police or not. But it’s really about building particular kinds of relationships and communities and practices, that doesn’t necessarily have to rely upon the police, or the larger carceral apparatus.

[00:40:20] Correia: Yeah.

[00:40:31] Intermission: You are listening to Macro N Cheese, a podcast brought to you by Real Progressives, a nonprofit organization dedicated to teaching the masses about MMT or Modern Monetary Theory. Please help our efforts and become a monthly donor at PayPal or Patreon, like and follow our pages on Facebook and YouTube, and follow us on TikTok, Twitter, Twitch, Rokfin, and Instagram.

[00:41:23] Siener: All right. Yeah, I just wanted to jump in real quick and go off of that. And that was one of the observations, as I started looking at things through a class analysis lens. It seems like police are set up as the only resource for poor people, basically, in an emergency, and they don’t make things better. But one of the things I noticed, listening to the Macro N Cheese podcast, is when you mentioned the coal miners striking in the early 1900s, and how the public opinion was police were pretty good, until they started seeing what was going on, and they were brutalizing the coal miners that were striking, to where it shifted public opinion to the coal miners’ side. And again, another observation I’ve made, as I started to see things a little more clearly, is just how much “copaganda” is in TV and movies, and just how thick and aggressive it’s laid on in everything.

And it’s almost like, you start making those connections and you start realizing why. And I just wonder if you could weave that into how effective it is. Does it need to be that effective, or they need it because of stuff like the public opinion shifting away from ‘the police are good’. If you can expand on that, maybe.

[00:42:35] Wall: One of the things that you said, and I think also in the context of neoliberal capital, where the social welfare state, whatever there was, has been gutted, it is the carceral apparatus, including the police that is still standing. And so in a lot of poor communities, it is the carceral police apparatus, that’s the only semblance of some type of welfare regime in these communities, and we have to contend with that.

[00:43:03] Correia: It’s pervasive. We don’t write a lot about that in the book. We focus a little bit on what we call counter-insurgency. A lot of what cops do, we would recognize as a counter insurgent practice, like coffee with cops, and take a bite out of crime, and the DARE program, shit like that. And actually, Tyler mentioned in Violent Order, the book that we co-edited, there was a chapter on Dexter, and there was another chapter too, that talked a little bit about the role of media and cops. I think that’s pretty important because it establishes a specific cultural content in which we ‘consume’ police. Which is much different than the version on the street.

[00:43:47] Wall: I think the question of copaganda, what you’re getting at John, is really important, because it also helps us think about policing as an idea that circulates in society in very pervasive ways. And so even storytelling, it’s so hard. Even if you watch a romantic comedy, it seems like the police in quote ‘crime’, which often then signals towards police is present. In even the most mundane kind of representations in Hollywood.

Just a little aside, I’ve never told anyone, man, I don’t know if you’ve seen the Nicholas Cage movie Pig, but one reason why I love it, and I won’t give any spoilers, but it’s a very kind of weird, eccentric movie about restaurant workers, and there’s definitely a class analysis built into it. The whole premise is, these people steal a truffle pig, and the guy that depends, and living on this truffle pig, and he just wants his pig back.

But why I think it’s so interesting, one day I wanna write something on this, is that the whole time, you think, as a viewer, it’s going to go towards, kinda like the Taken series. You’ve taken my pig, now I’m gonna come and kick your ass, or I’m gonna call the cops, and they’re gonna kick your ass. And it doesn’t do that.

It’s a movie that has no cops in it. But the whole time as a viewer, you think it’s gonna go there, and it kind of subverts it. But I think copaganda should be addressed on two levels. One is, there’s a concerted attempt, there’s a parallel here with military, and there’s books written on the links between the military and Hollywood, and how the military won’t give even certain technology to producers and directors, unless they get to review the script.

And there’s definitely a long history of that, of police being consultants for Hollywood, with explicit purpose of promoting pro-cop representation. But then there’s also that other thing about, why true crime is so popular, is because it’s not just pure manipulation. There’s a certain kind of identification with it.

It’s part of the very, kind of, narrative fabric of our lives, where there’s an explicit, intentional manufacturing of a pro-cop world. But there’s also this larger, when we think about order, we tend to think about police, and then threats to that order, and so there’s something also very diffuse about it too, if that makes sense.

[00:46:12] Siener: Yeah, absolutely. And again, I didn’t watch TV for a while and then I would put it on in the background and I was just blown away by how many CSI, NCIS, Law and Order, etc.. There’s like a million cop shows and it’s all to paint the police as this honorable, moral code, and all this other stuff, and it’s just crazy, just how much there is.

[00:46:35] Correia: Also, even the stuff we might think of as critical, or something like The Wire or something, also trades in this familiar, “the job”, the individual cop burdened by the system, trying to fight both the system and crime. And so it does position cops as honorable figures, even in The Wire. So it’s everywhere. I agree.

[00:47:01] Siener: I tell people the most accurate representation of cops in TV and media, is cops on The Simpsons.

[00:47:07] Correia: Yes.

[00:47:08] Wall: Yes.

[00:47:09] Siener: We’re moving on to Jonathan Kadmon. Go ahead and unmute your mic buddy.

[00:47:15] Jonathan Kadmon: Hi, pleasure to make your acquaintance in person. I have a great interest in this topic. I did read the book, but it was short, so I took the liberty of rereading that book that I had told you about, in preparation for this. Which honestly, the thing that strikes me is, the degree to which a lot of this did start, as you described in the podcast, in the private sector, and there was a process, probably around the time period you described, of beginning to insource these things into the public sector. But as you pointed out, in several little entries in the field guide, that hasn’t diminished the private sector. There’s more security guards out there now than there have ever been in the past. And many of these same organizations remain around.

Pinkerton and Burns have merged and are part of Securitas. And I wondered if you would talk about how private actors are instrumentalized by these quote unquote “public police forces”, not just security firms, but also civic organizations. Back in the World War I era, you had the Liberty League and the American Legion, and today you have these misinformation organizations that are handing lists of people to the FBI to hand to Twitter, and so on and so forth.

[00:48:33] Correia: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. I wonder what entry you’re thinking of. In the revised version, we wrote a few entries that really got into this a little bit more, than in the 2018 one. And I’m thinking of, there’s an entry in the new version called data center, that I think gets at the privatization of policing.

But it’s a different iteration of it, and it’s something that I was really spending a lot of time, at the beginning of the pandemic, investigating, after the Blue Leaks hack. I don’t know if y’all are familiar with that, if you haven’t read the book. We mentioned in the book, Anonymous, or somebody, some hackers, broke into, I’m not sure what exactly they broke into, I think it was one of the fusion centers. Every state in the United States now has what are called ‘fusion centers’, which are supposed to be huge public sector data centers that connect all the data that all the various police agencies collect. So state, municipal police, and all the county sheriffs, and then you’ve got Feds.

And then, even within a city like Albuquerque for example, there’s like seven different police departments. There’s an open space department, metropolitan Police, and there’s the municipal development has their own police. And they’re all collecting data. And then there’s all these private firms that are selling to cops like vendors, private vendors, selling machines to cops, so they can capture license plates, facial recognition, videos that they then are stitching together, so that like in Albuquerque, for example, hotels and restaurants and retail setup, connect their video to the realtime crime center police and the realtime crime centers, and connected to the fusion center in Santa Fe.

And so when Blue Leaks dropped, I mean, this was like data from every department, and the thing that I noticed, which I thought was fascinating, was the way in which, I don’t know if this is the right phrase we use, correct me if I’m wrong, but, cops are like Silicon Valley drug mules. That’s basically what cops are. Seven or eight private vending firms, selling cops various different devices or machines to capture data, but then they’re holding that data on private servers, that cops can access. But those private firms, like Cellebrite for example, they’re harvesting social media data for cops. The firms that capture license plates, facial recognition, all that stuff’s private. So that cops are basically just collecting data for private firms, that are then monetizing that in all kinds of ways. And so it’s almost impossible to really define policing now, because of the extent to which the information that cops collect, finds its way everywhere.

If we’re gonna talk about police, I would say probably the most sophisticated police agency in the United States, is the Target corporation. Who has the most sophisticated police labs, that hires F B I and local police, and then just gives that resource to local municipal police departments, seeding local municipal police departments with funds, so they can create little mini arrangements among retailers, and hotels, and neighborhood associations, who will convince their members to connect their Ring cameras to the police realtime crime center.

If there’s one good thing some criminologists do, is point out how worthless all this stuff is. If the goal is crime fighting or public safety, it does nothing. It doesn’t do anything for any of this. It’s just very expensive, and then connects cops to these private firms to produce data for them. So in other words, policing now is this enormous activity that involves huge numbers of unknown private vending operations.

It’s not like the Pinkertons anymore. It’s tiny little operations in Austin, with server farms, holding enormous amounts of police data, trying to figure out ways to monetize it. And reporters didn’t give a shit about the Blue Leaks. The Intercept wrote four or five articles. Some of ’em were pretty good.

Nobody else gave a shit about it. It was fascinating, the extent to which the most sophisticated data collection machines and software programs, are in the tiniest little departments. They don’t even know how to use them and what to do with it, and they’ve totally turned that over to the private sector, who just are using police to capture data.

So this is really fascinating policing now, even the anarcho-capitalists of Silicon Valley love cops, because of the way in which they serve their needs to acquire more data. I almost don’t even know where to stop when talking about this, because it’s kind of bizarre, but also really amorphous, in its role in reinforcing the authority of police, because cops produce money. Local municipal police departments is a source of revenue for the private sector.

[00:53:39] Cotts: I have a question from Jules. ‘So how do we get past reform and get to abolition, when, as you mentioned on Macro N Cheese, if we abolish the existing institution, all the cops just become private militias hired by the wealthy, to continue their arrogant prerogative of protecting capital, and we are left without protection from that.’

And I wanted to add to that, people are talking about this idea of the private police. We’re looking at that in the intelligence community, privatization of military, internationally, and intelligence. But also, people are talking about the cameras outside of stores, and in restaurants, and Jules said the option to connect storefront cameras to the police network is up for a vote in her town.

And I also wanted to ask you, and I’m sorry I’m going on, but in some of the TV shows about England, they always have the CCTV. Those cops can cover every inch of their city, and it must be a combination of private and public, I assume. I’m told by a British friend that it’s true that they have that, it’s not just fictional in cop shows. But do you know anything about that?

[00:55:04] Wall: I was just gonna, I think, adjust, what was Jules’ question, about how do we get past reform into abolition. But I think what I would say to that is, abolition is not something that just happens in the future, if that makes sense. Abolition isn’t something that is just in the future, so you have a lot of people saying, ‘oh, I’m on board with abolition, but not today’.

Yeah, at some point that’d be great. So abolition, it’s not something that just happens in the future. It’s something that you try to practice now and build now. But it’s not something you have to wait for, in the sense that’s what we’re talking about, like ‘build the block’ or call chains, and other ways of handling problems in neighborhoods and what not.

But that’s today’s work, as opposed to waiting for this to happen, which means then there has to be serious thinking about what is reform, what are the reforms that are, what the abolitionists call the ‘non reformist reforms’, which are the reforms that cut into the power and scope and capacity of policing. And not the ‘reformist’ reforms, which are those typical reforms that we talked about, that shore up the legitimacy of policing.

That’s a struggle and a process of working through that now, and then trying to build different kinds of communities, different kinds of institutions, dual power, in order to create better communities, a better world, so to speak. I don’t know if you have anything to say on that, David.

[00:56:26] Correia: I was thinking of Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s great answer to this skepticism of abolition, which is, this is not an absence. To talk about abolition, I’m not talking about an absence, an absence of safety, or an absence of security. It’s the opposite of that. Think of all we’re robbed of by capitalism and cops. Capitalism is a machine to destroy social relations. That’s what it does. Capitalism just obscures and destroys social relations. And the job of cops then, are to hold that chaos together, so there can be industrial stability and everyone can make money, or at least some can. And so, abolition is not about some sort of future goal of a world free of cops, but of a present, that is more present of those social relations, we’re robbed of.

And that requires a lot of work, a lot of practice. It’s a practice. I think that I wanted to just add Ruth Wilson gilmore’s, words in that.

[00:57:24] Wall: The other way, real quick, of saying that is, abolition is not just a negative, in the sense of tearing things down, or tearing things down, then building. It’s kind of a simultaneous process of trying to dismantle, but at the same time trying to build and produce other kinds of social relations, other types of institutions, organizations, practices.

[00:57:48] Correia: Yeah.

[00:57:49] Siener: Yeah, absolutely. All right. Our good friend Bakari is here and he’s got a question. Go ahead buddy.

[00:57:56] Bakari Chavanu: Hey, thanks a lot. I think my question has already been asked. I wanna just maybe, while I have the floor. I think that abolitionism is something that you don’t just do that independent of the other struggles around, de-capitalizing the society, providing resources for people, talking about what ‘modern money theory’ means, in terms of the government spending money, to shore up the deficits in the economy, housing, food, healthcare. I think if you’re not working on those things at the same time, you can’t really focus on abolitionism. You have to do both. They’re not separate.

And that’s what I tried to explain in the thread that I was in on YouTube yesterday. They’re talking about these businesses closing down in San Francisco, that’s what my question was about. And people were blaming it on this call for abolition, and blaming it on BLM. And I said, no, it’s really a serious skyrocketing of the cost of living in San Francisco, a lot of desperation. Really, you gotta talk about people being desperate economically, financially, not having good jobs, dealing with drugs, dealing with other kinds of issues, that you gotta address, when you’re trying abolitionism

so that’s not really a question, but that’s just my input.

[00:59:13] Correia: Yeah. Great. Thank you.

[00:59:16] Wall: Yeah, I would just say any discussion of abolition of police and prisons, has to be thinking about the abolition of capital and private property, and it’s not a coincidence. That was exactly the way that Marx and Engels talked about it in The Communist Manifesto. Abolition was a term that was very much a part of their lexicon, the abolition of existing property relations.

[00:59:38] Siener: Damn right! Yeah, and I think a big hurdle is people still kind of see police as public, like a public servant or something, and they’re about as public servant as our Congress people are. And I think getting past the idea that we need them, is a big step to getting there.

Next up we have a question from the big cheese, Steve Grumbine. Steve asks, what are other strong organizations and efforts we can support in this?

[01:00:08] Correia: The effort to stop Cop City in Atlanta. This would be a current campaign. I think we mentioned Interrupting Criminalization, which is I think a really important effort to combine political education with practical efforts, to build alternatives to police, would be a couple I would suggest.

[01:00:27] Wall: I would throw in Critical Resistance.

[01:00:31] Cotts: Angela Davis’ group? Is that what you’re talking about?

[01:00:35] Wall: She was a co-founder with Ruthie Gilmore, and Rachel Herzing, and a variety of people back in the late nineties. But really a key organization that’s put abolition on the map, so to speak, in many ways. Their website too, is great, with all kinds of resources. But yeah, interrupting criminalization, critical resistance. Also, these organizations are popping up in local communities. There’s struggles going on everywhere.

[01:01:07] Siener: All right. Got a question from Maple in the audience.

[01:01:13] Maple: Yeah, I thought about the ‘Guardian Angels’. I’m 68 now, and I remember hearing about ’em, I was maybe mid-teens, and so that’s kind of an example. They took it upon themselves, and I think the New York City budget was getting low or whatever. Do you have any stories? Did they have permission to do that? I don’t really know the background. I just thought maybe you guys had looked into that a little bit, and I’m learning so much. Thank you so much for everything, this is great. This is all new to me, kind of, except the violence. I’m white, and I’ve been pulled down to the ground for nothing, a few times already, in my sixties, being a protestor that.

So I’ll probably go back to Atlanta next week. I was there a year ago, but yeah, it’s a real problem, it’s terrible. Thank you.

[01:01:57] Wall: I think the ‘Guardian Angels’, I don’t know a lot about them, other than I’d just say that I’m quite hesitant to think of them as abolitionists. My understanding is, they’re a quite conservative group, who work very much hand-in-hand with the cops. And if I remember correctly, the founder, I think, Curtis Sliwa, he’s a pretty conservative politician, that just ran for some…

[01:02:22] Correia: Tries to be a politician.

[01:02:23] Wall: Tries to be a politician. But to my understanding, I remember when I was a kid, I was in martial arts, and that’s where I first learned about them. It was a very pro-police organization. I think by me and David’s definition, they would be thought of as, police.

[01:02:39] Correia: Police.

[01:02:40] Wall: Not intensively a community controlled police, but a very particular, still reactionary, kind of police force.

But there’s the other parallel, which would be the Black Panthers. That did police their own communities and also did other types of programs, like free breakfast, this and that, but they were linked. And that was in direct opposition to police. So it wasn’t working with the police, it was saying, we’re gonna handle this on our own. We can set up some type of other apparatus or practice in order to handle community problems, without relying on the capitalist state.

[01:03:17] Cotts: The Panthers were patrolling the police.

[01:03:22] Correia: The Guardian Angels, it’s an interesting case, and it’s a good question. Because if you look at Albuquerque, for example, Albuquerque has a long history of militia activity. It’s always been cop adjacent. It’s always been staffed by cops, or former cops, or former military. It’s never gone away. It emerged again in 2020, during the uprising after the murder of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. And that’s the only parallel armed group cops will permit. The Panthers were targets of police, because they refused to be enrolled into the police project. So groups like Guardian Angels could only exist because they had the consent of police to do it. Every police department has people whose job it is to build those relationships with community groups, to do community policing.

[01:04:18] Wall: Neighborhood watch.

[01:04:20] Correia: But it can’t occur outside of the consent of police, because then it’s a challenge to the authority of police. Tyler and I love Walter Benjamin, and Benjamin’s argument is, all law at its first instantiation is against the law. Any challenge to the authority of law has to be destroyed. The Guardian Angels fit within this logic of policing.

In Seattle in 2020, when they tried to set up that ‘police-free zone’, they were just constantly under the assault of police, and there’s no way to build that formal, organized, particularly armed, alternative to police, without finding yourself targeted by police.

[01:05:09] Siener: Indeed. We’ve got our close comrade Cheryl Van Epps who wants to jump in and ask a question.

[01:05:18] Cheryl Van Epps: Hi, David and Tyler, thank you so much for speaking to us tonight. On Facebook, a Dutch friend shared with me how their police had to account for each and every bullet they shot after a non-lethal shooting. Have any of our major cities or communities looked into how the European countries do, in my opinion, a much better job policing, and how they hold their cops accountable.

Thanks.

[01:05:47] Correia: There’s a lot of examples of it. I think even in that example, ‘where did your bullet go?’ Well, it went into the body of the person I killed, so now we know where it is. And I don’t wanna be flippant about that, but let’s put it this way, most white people in this country, live in a world that, for all intents and purposes, doesn’t include police.

They don’t see police. Police don’t show up at their house. They don’t ever really have to call police. They’re not tailed by police, or pulled over by police. For them, police is not a problem. They have the kinder, gentler version of police, and so that’s one of the victories of reform, which is to establish the goal of just, less violence.

Just, let’s take the hard edge off, as if that’s the problem. If the grinding daily violence and harassment of police is a 10, let’s just dial it down to a 5, and are we all happy now? Maybe some people will be very happy with that. That doesn’t undo any of the purpose and role of police in society that we’ve been talking about. But at the same time, in 2014, after the police murdered James Boyd, and I was working with a lot of organizers on the ground, and I was spending a lot of time with family members of parents of kids, who’d been killed by cops. Their goal was, can we just stop the next person from being killed? They had a very practical, pragmatic goal.

Can we just save one life? And that’s important. That’s not unimportant. And that’s, I think, about this non-reformist reforms. So Cheryl, that question is important in the sense that, okay, well, what are the proposals that are gonna get us there? And if those are proposals that reduce the ability of cops to kill, to brutalize, or harass, then okay, let’s support that.

We should support that. It’s not the victory we’re looking for, but anything that shrinks police, gets us closer to that victory. So yeah, I think if that’s the context we’re talking about, then that’s really an important one.

[01:07:42] Wall: Yeah. I was just gonna add too, that it is true that police in the UK, for instance, don’t kill near as many people as the police in the United States do. But the police in the UK still predominantly arrest and harass the poor, and that’s racialized and classed. But policing, historically, the way that it operates, is it predominantly focuses on the poor and the working class, no matter where you are, that’s a generalized quality.

All you gotta do is go to the jails in any other country, and what you find in jails, are predominantly poor people. And so, in the US, there has always, historically, been focus on the police killing of people, and that is, David said it’s very important, but then often then this discourse gets entered, ‘well, we can do policing like they do in Europe’. Same as US, Canada. We frame Canada as so much better, but then we forget it’s like their colonial history, the fact that the police there also predominantly focus on indigenous people and the poor. So it’s not just about direct lethal violence, it’s about that administering of order, a class order.

[01:08:59] Cotts: Okay. We have another question from Steve Grumbine… How do we avoid creating libertarian warlords? It seems, going back to the dissolution of the Roman Empire, chaos and death ensued, followed by warlords and such. Is this just propaganda, or is this a real thing to concern ourselves with?

[01:09:26] Correia: I don’t even know where to begin to answer that question.

[01:09:28] Wall: I know.

[01:09:30] Cotts: Well, it’s the Roman Empire, so you’ve got a lot of time to fill in.

[01:09:36] Correia: It’s 8:30 my time. Wrap it up in one minute, Tyler.

[01:09:40] Wall: I don’t I know how to really get at that, exactly what you’re meaning by libertarian warlord. I’m interested in that.

[01:09:49] Siener: I just think he’s referring to the idea of abolishing police. What would be left behind or what would fill its place.

[01:09:58] Correia: No one who’s talking about police abolition is advocating that we just tomorrow unleash 10 million unemployed armed cops. That’s not anyone’s idea of a good idea. Unless they’re a libertarian warlord, I guess. They would have an army available to them somewhere.

[01:10:21] Siener: We’ve actually got Steve Grumbine here. He wants to elaborate. Go ahead buddy.

[01:10:27] Grumbine: What I’m trying to get at here is not obvious, because I had the pleasure of being in the interview with David, so I’m actually further ahead, than maybe that question read. What I was trying to say was, in terms of signals that things are starting to happen. We saw before the police, we had the private police, that work with capital to begin with, and you had already said it, you get rid of the police now and you end up with private police.

If you don’t make all these fundamental changes, and the idea is to get rid of capital, but these are big, lofty things when it comes to that stuff. But my question is, we can’t even get basic things passed, with this, just like, fake Congress, so to me, short of revolution, how do you bring these things to bear?

And if you do bring it in chunks, back to what Bakari was saying, that without doing away with private property, and fundamentally taking away that destitution factor, there’s gonna be these problems. And one of the things, we’ve all seen, is private police, private mercenaries, we even deploy them in police actions around the globe, private militias.

So I guess my question is, what keeps the pendulum going from the other way, and then what do you do? This is me genuinely playing that out so that I can be ready, because I wanna be involved.

[01:11:54] Correia: Yeah.

[01:11:54] Grumbine: And maybe misguided, that’s why i said as

[01:11:57] Correia: That’s why, at the end of our podcast, we were talking about union organizing. Which is not to say, everyone go join a union, because you can’t. But rather to say that, the only way to make these kinds of transformations, is through social movement struggles. So it has to be a mass movement of people that are pushing this.

Tyler and I were talking about this before we wrote the second edition. In the first edition, no one was talking abolition. I was in meetings with the most radical people in Albuquerque, and when someone talked about abolishing the police, they were just shouted down. This was in 2014, and then by 2020, this was millions of people in the street, calling for the abolition of police, or the defunding of police.

I was shocked at how the language of abolition had taken hold. And then, of course, immediately we knew what the backlash would be. There would be this enormous backlash, and of course it happened. But the fact that the language of police captured the imagination of so many people, brought people into the street, means that this is not some ‘pie in the sky’, small group of crazies, over here talking. This idea and this argument can really capture the imagination of people, and produce this huge social movement. But we shouldn’t be fooled by this. Cormack McCarthy just passed away, and I was reading something he had said one time. I think it was about Blood Meridian in one of his books, and he was saying he just doesn’t trust people who ignore this violence of life. There is no ‘Kumbaya’ future for us. We’re gonna have to confront these forces at some point, and better to do that when there’s 10 million of us, than a handful of us taking pot shots at cops, from behind cars, in an alley, in a protest in Seattle. That’s not a good strategy. That’s not gonna get us anywhere.

We need this huge mass social movement to confront this force, because this is an order that is breaking down, the order that police have been able to fabricate and maintain. It’s not something that police can continue to maintain the way they are. So this is shifting, it’s constantly shifting. The reform is the constant recalibration of police to meet the challenges that police are no longer able to meet.

But there’s nothing we’re gonna be able to do about that, without this huge movement. And so to talk about abolition, is to talk about that movement. Without that movement, then we’ll have the libertarian warlords. We have all kinds of warlords, not just libertarian warlords. That would be the result, without building the solidarity. And let’s not just make this about a left movement. In 2014, we had people from the right coming to these meetings, challenging police, and it was a fragile coalition and it splintered quickly. But we’re not gonna have a mass movement, if we’re not setting aside these purity tests we have for our politics.

[01:14:45] Grumbine: Well think about the private property element of it. That is a huge part of the entire mindset of a Republican/Libertarian is 100% private property. Dissolution of any government institution, and privatize all. So the fundamental war, if you think about it, isn’t the police, it’s private property.

And if you go that far, then it’s a strange bedfellow indeed. I don’t know how that works. So I’m interested in your thoughts.

[01:15:16] Wall: I appreciate the question, Steve, and the conversation. I think it is about that question of private property, but I don’t know if you can have that without police, which again leads me to, to get to that other side, you’re gonna have to go through policing on some level. As both an idea, but also as a real ‘capital’s last resort’, that stop gap.

And I don’t think that’s an easy thing. And so I think it is about building an anti-capitalist politics. But I think my position is, to really build an anti-capitalist politics, that’s when you’re going to be confronting the police, because that’s the function of policing in a capitalist society, is to maintain that capitalist-property relation.

I dunno if this really addresses your question, but, and I listened to your podcast talking about the past, is that I think, it’s more, the critique of capital, really is important. Whenever I teach police class, if you don’t throw in a critique of capital, and the broader economic relations, I learned this the hard way, it was often the libertarian kids that were coming up to me after class, really digging my critiques of police. They didn’t necessarily oppose police, but they opposed the militarization of police, which is a discourse that very much comes out of the right libertarian movement. I knew this, but it’s easy to forget when you’re in the classroom teaching that, you can critique the police, and then you get the libertarian students that actually really like it. And then the way to counteract that, is to try to bring in the discussion around the question of private property, and then the police’s position within that larger system. But we have to have a critique of capital, in order to avoid the libertarian critique of police, which there is, there is very much, right? The ‘government of wolves’. There’s this libertarian critique of police, that’s very much ‘out there’, but it’s not so much anti-police or abolitionists, it’s just police overreach, onto private property.

[01:17:21] Correia: Yeah.

[01:17:22] Wall: Ruby Ridge, and that kind of critique of government power and police power.

[01:17:28] Siener: Yeah, I agree. And as a card-carrying communist, when I argue with Libertarians about the government, and I try to be like, ‘look, it’s a tool and it serves the ruling class’, and that’s police, it’s a tool that serves the ruling class. And right now, that’s the rich and corporations.

We’re gonna wrap it up pretty quick here, guys. We’ve got this one last question, you wanna throw something on it, and then if you wanna let everybody know how they can check out your content, and find you on social media?

So we’re gonna combine this, they’re similar questions here, and I’ll just read it out. Y’all can give a little, couple words.

Cole says, Crime is a feature, not a bug of capitalism, how do we address the real issue of intentional scarcity? And Mark says, Should we be more focused on ending the reasons for most crimes, which numerous studies have linked to poverty?

[01:18:18] Correia: You only find crime where you find cops.

[01:18:24] Siener: Yeah.

[01:18:26] Wall: I was gonna say, the link between poverty and crime is also quite complex, because we have to be careful in the way that we frame that question, because it can lend itself to thinking about crime as predominantly just the work of the poor, without taking into account elite crimes. But also, not everybody that’s living in poverty is out committing all kinds of crimes too. And so, I don’t know if this necessarily answered the question, but I hope no one thinks that we are discounting the realities of actual harm. Those are real things, and they are often concentrated in exploited communities. And I think what abolition is trying to do, is not deny that, or disown it, or ignore it, but actually to recognize that the current system that we have in place, actually exacerbates those harms and doesn’t actually do anything to alleviate the harms, in the first place.

Abolition as a political project, isn’t a project that’s denying the reality of violence and harm, or framing violence as only a product of the state. That people do harm people, and that’s a real thing. We don’t need to deny that. We need to actually confront it, and I think that’s what the abolitionist project is trying to do, is to say, there’s other ways of handling this. And then, yes, there has to be this larger systemic shift, that actually, totally, reorganizes society in a way that provides healthcare, and good paying jobs and, this and that.

[01:19:59] Siener: Yep. That’s the thing, if you starve communities of resources, you’re gonna create theft, and petty crime, and that kind of stuff. And again, that goes back to what you guys said about having to have that analysis of capitalism, and bringing that into the conversation, because it all connects.

So if you guys wanna let everybody know where they can find you, where they can find your content.

[01:20:23] Correia: I’m not on social media, so that makes it easy. But you can find our books at bookstores, particularly anarchist bookstores, or any bookstores. Tyler and I have written, Police: A Field Guide, and edited a book, and then I’ve written a few other books, and so check those out. I would hope that you would do that.

[01:20:43] Wall: Yes. I’m also not on social media. I mean, I was reluctant to even do this.

[01:20:48] Correia: And no, I had to talk him into it

[01:20:51] Siener: Well we appreciate your guys’ time, and I’ll see what we can do to get your books in our RP bookshelf, if they’re not there already.

[01:20:58] Cotts: So, we wanna thank you guys, your generosity with your time, this was great. Tyler, I would’ve had no idea that you were resistant,

[01:21:09] Correia: right when he starts

[01:21:10] Wall: talking,

[01:21:10] Correia: but it just.

[01:21:11] Wall: starts.

[01:21:12] Cotts: But this was wonderful. And we wanna thank everybody who came, and you know that Real Progressives needs your help. Share our stuff on social media, read our articles, listen to the podcast, Macro N Cheese.

And we have a donation link on the website, and we have a Patreon. Commie John, you wanna talk about all that?

[01:21:40] Siener: Yeah, if you go to our website, Realprogressives.org, it’s just a treasure trove of resources. And, as you know, if you know the Macro N Cheese Podcast, it just covers so many different topics, and it’s not just MMT centric, necessarily. And if you want to hit us up on Patreon, throw us a few bucks. It is patreon.com/realprogressives, and we do appreciate our generous donors. Again, hit us up on social media, TikTok, Facebook, all the regulars, and I guess we’ll see you the next one.