One of the founding myths of modern economics is the claim that money developed as a medium of exchange specifically to overcome the limits of bartering. It’s an old idea that goes all the way back to at least Aristotle, but in more recent times it was championed by Adam Smith and it’s become an article of faith everywhere from college textbooks to the elite intellectual circles of academia.

According to the standard version of the story, the world before money was cumbersome and inefficient. In order to trade goods with other people, you had to have exactly what they wanted and they had to have exactly what you wanted, the famous “double coincidence of wants.” If you have shoes to trade and want eggs in return, but the other guy who has the eggs actually wants milk, then you two will not be able to exchange your goods. But the invention of money solved this problem quite nicely. As long as you have it, you can always use money to buy anything for sale in a market. You’re not restricted to trading with someone who will only accept milk or eggs because everyone will accept money. The big achievement of a monetary economy, according to the standard neoclassical view, was to help facilitate more market exchanges and transactions. In effect, money acts as a kind of lubricant for market activity; it lets people trade more and faster. It’s a nice story, but it’s also dead wrong.

From David Graeber to Richard Lee, anthropologists have long demonstrated that virtually all contemporary yet pre-modern societies, along with most ancient societies, distributed resources on the basis of credit and social trust, not tit-for-tat exchanges. Early economies mostly operated through gift-giving and communal sharing; there was virtually no market exchange of the kind that we see in our world. Overlapping systems of credit and debt governed the process of economic distribution. People would share things with each other by simply making polite demands on the basis of social trust and custom. Failure to share with members of your community could lead to social ostracism and exclusion. Once a person gave something away, like a fish, the other person receiving the gift became indebted to the creditor, meaning she had to give something back to the creditor in the future. She could settle the debt through anything considered roughly equivalent by the standards of her society. For example, a spear might be seen as having about the same worth as a fish, so she could give back a spear to the person who gave her the fish. Notice that there’s no immediate exchange here; the fish is given on credit, on social trust, and the spear doesn’t have to be given back until much later. There’s no bartering happening either; the fish and the spear are not getting traded at a fixed point in time. In fact, they’re not being traded at all. They’re being used as accounting tools to satisfy a social obligation. Any other objects or resources would do, as long as they’re perceived to be roughly equivalent. Settling a debt with something perceived as vastly unequal or deficient could lead to resentment and even violence.

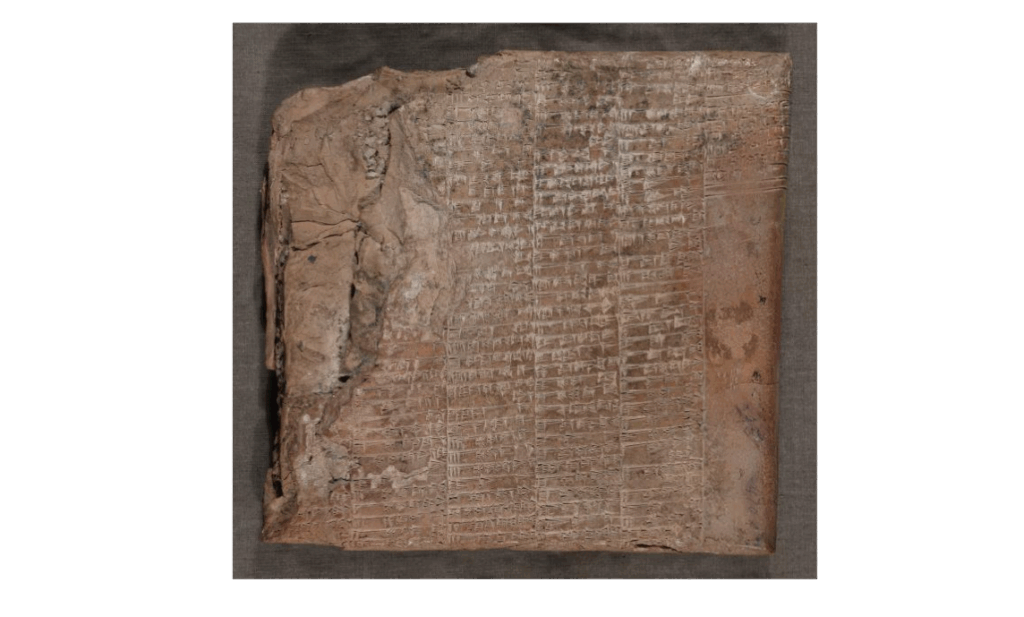

Credit dominated even among the early ancient societies that used various forms of money, like the Sumerian civilization. The Sumerians did have silver rings and ingots and denominated much of their debts in silver. But as Graeber pointed out, most people didn’t actually settle these debts with silver because they simply didn’t have any, so credit was the order of the day. People would show up at the local tavern or temple and borrowed what they needed or wanted on credit, then later paid back their debts with whatever they had, usually with their crops and grains.

Furthermore, the double coincidence of wants is a fake problem that exists in the imagination of bored economists. In the real world, people grow up in common social environments, meaning that their desires are highly correlated and socially constrained. No one who grows up in a typical social environment has completely random and arbitrary preferences. It’s almost inconceivable that someone in an ancient village would have wanted something that his wider community did not have. Even in the modern age of capitalism, where people are overwhelmed by millions of options and commodities, our desires and preferences are still influenced and constrained by our social communities.

Why do economists care about the history of barter and money in the first place? Neoclassical theorists repeat this nonsense because it’s a way of justifying and excusing the grotesquely corrupt distribution of wealth under modern capitalism. The idea is simple: if what you get in life is determined by free and fair exchanges in an impartial market, then the resulting distribution of resources is also fair and, in some sense, “morally just.” This is the fundamental reason why neoclassical theory is obsessed with the concept of exchange: it’s a way of hiding and obscuring the social relations and power dynamics that actually determine who gets what in life. There’s something about the concept of exchange that feels so reciprocal and mutually acceptable: you give me what I want (shoes), and I give you what you want (money). I have comprehensively refuted this silly position in many of my Substack posts, which you can read for free. The main problem for the neoclassicals is that the terms and standards which govern the exchange process are themselves determined by other factors. The distribution of wealth, and virtually all other economic outcomes, are strongly affected by everything from wars and natural disasters to political and class struggles. These factors collectively impose powerful constraints on how market exchanges happen. Focusing on the process of market exchange is just a cheap trick for marginalizing these large-scale degrees of freedom. Markets never bring about order on their own, they emerge from pre-existing political and economic orders. They are not spontaneous, but constructed.

Originally posted at https://substack.com/@technodynamics/note/c-125005177

Find out more about Erald’s work at www.eraldkolasi.com

1 thought on “The Barter Lie: How Capitalism Rewrote Economic History ”