Originally published December 25, 2011 on the New Economic Perspectives blog.

Yet another rescue plan for the EMU is making its way through central Europe—with the ECB acting as lender of last resort to Euro-banks. It is trying the tried-and-failed Fed method of rescue. As we now know the Fed lent and spent over $29 TRILLION trying to rescue (mostly) US banks. It did not work. The biggest banks are still insolvent, and have continued their massive frauds trying to cover up their insolvencies. You cannot paper-over insolvency through massive lending by the central bank. And the Euroland problems are compounded by the insolvencies of virtually all their member states.

To be sure, we also have probable insolvencies of some of our US states—but we’ve got a sovereign government that will eventually do the right thing (as Mr. Churchill famously said, Americans get around to that, after trying everything else first). But the Euro states do not have any sovereign backing them up. And note that the ECB remains unwilling to do the job. A disastrous financial collapse and possible Great Depression 2.0 remains the most likely scenario.

How Did Euroland Get Into Such A Mess? PartOne: Private Debt

We all know the favourite story told: profligate-spending Mediterranean governments blew up their budgets, causing the crisis. If only they had followed the example of Germany—as they were supposed to do once they joined the Euro—the EMU would have worked just fine.

While the story of fiscal excess is a stretch even in the case of the Greeks, it doesn’teasily apply to Ireland and Iceland—or even to Spain—all of which had low budget deficits (or even surpluses) until the crisis hit. In truth, there were two problems.

First, like most Western countries, private sector debts blew up in many Euroland countries after the financial system was de-regulated and de-supervised. To label this a sovereign debt problem is quite misleading. The dynamics are surely complex but it is clear that there is something that is driving debt growth in the developed world that cannot be reduced to runaway government budget deficits.

Nor does it make sense to point fingers at Mediterraneans since it is (largely) the English-speaking world of the US, UK, Canada and Australia that has seen some of the biggest increases of household debt—the total US debt ratio reached 500%, of which household debt alone is 100%, and financial institution debt is another 125% of GDP.

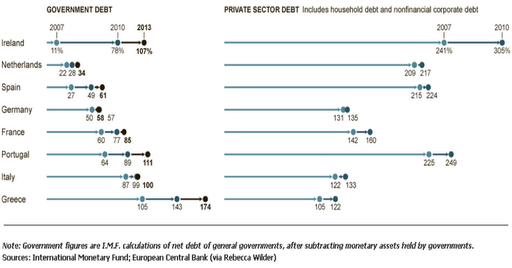

Take a look at this graph, which shows the debt-to-GDP ratios for the private and government sectors:

Clearly, upto 2007 the really big debt ratios were in the private sector. The story is very similar to that of the US. But note that the problem tends to be worse in those countries with smaller government debts—there is an inverse relation between private debt ratios and government debt ratios. Now why is that?

And as we know from previous MMP sections, the sectoral balance identity shows the domestic private balance equals the sum of the domestic government balance less the external balance. To put it succinctly, if a nation (say, the US) runs a current account deficit, then its domestic private balance (households plus firms) equals its government balance less that current account deficit. To make this concrete, when the US runs a current account deficit of 5% of GDP and a budget deficit of 10% of GDP its domestic sector has a surplus of 5%; or if its current account deficit is 8% of GDP and its budget deficit is 3% then the private sector must have a deficit of 5%–running up its debt.

{An aside: A big reason why much of the developed world has had a growth of its outstanding private and public sector debts relative to GDP is because we have witnessed the rise of BRIC (and others—especially in Asia) current account surpluses—matched by current account deficits in the developed Western nations taken as a whole.

Hence, developed country budget deficits have widened even as their private sector debts have grown. By itself, this is neither good nor bad. But over time, the debt ratios and hence debt service commitments of Western domestic private sectors got too large. This was a major contributing factor to the GFC.}

Our Austerians see the solution in belt-tightening, especially by Western governments. But that tends to slow growth, increase unemployment, and hence increase the burden of private sector debt. The idea is that this will reduce government debt and deficit ratios but in practice that does not work due to impacts on the domestic private sector. Tightening the fiscal stance can occur in conjunction with reduction of private sector debts and deficits only if somehow this reduces current account deficits. Yet many nations around the world rely on current account surpluses to fuel domestic growth and to keep domestic government and private sector balance sheets strong. They there for react to fiscal tightening by trading partners—either by depreciating their exchange rates or by lowering their costs. In the end, this sets off a sort of modern Mercantilist dynamic that leads to race to the bottom policies that few Western nations can win.

Germany, however has specialized in such dynamics and has played its cards well. It has held the line on nominal wages while greatly increasing productivity. As a result, in spite of reasonably high living standards it has become a low cost producer in Europe. Given productivity advantages it can go toe-to-toe against non-Euro countries in spite of what looks like an overvalued currency. For Germany however, the euro is significantly undervalued—even though most euro nations find it overvalued. The result is that Germany has operated with a current account surplus that allowed its domestic private sector and government to run deficits that were relatively small. Germany’s overall debt ratio is at 200% of GDP, approximately 50% of GDP lower than the Euro zone average.

Not surprisingly, the sectoral balances identity hit the periphery nations particularly hard as they suffer from what is for them an overvalued euro, and lower productivity than Germany enjoys. With current accounts biased toward deficits it is not a surprise to find that the Mediterraneans have bigger government and private sector debt loads.

Now, if Europe’s center understood balance sheets, it would be obvious that Germany’s relatively “better” balances rely on the periphery’s relatively “worse” balances. If each had separate currencies, the solution would be to adjust exchange rates so that our debtors would have depreciation and Germany would have an appreciating currency. Since within the euro this is not possible, the only price adjustment that can work would be either rising wages and prices in Germany or falling wages and prices on the periphery. But ECB, Bundesbank and EU policy more generally will not allow significant wage and price inflation in the center. Hence the only solution is persistent deflationary pressures on the periphery. Those dynamics lead to slow growth and hence compound the debt burden problems.

How Did Euroland Get Into Such A Mess? PartTwo: Government Debt

To be sure, the private debt problem—related to the internal European dynamics of a strong mercantilist Germany in the center—would be very hard to resolve. But Euroland has an even more fatal problem: the Euro, itself.

So let us turn to that second problem.

The fundamental fault with the set-up of the EMU was the separation of nations from their currencies. It was a system designed to fail. It would be like a USA with no Washington—with each state fully responsible not only for state spending, but also for social security, health care, natural disasters, and bail-outs of financial institutions within its borders. In the US, all of those responsibilities fall under the purview of the issuers of the national currency—the Fed and the Treasury. In truth, the Fed must play a subsidiary role because like the ECB it is prohibited from directly buying Treasury debt. It can only lend to financial institutions, and purchase government debt in the open market. It can help to stabilize the financial system, but can only lend, not spend, dollars into existence. The Treasury spends them into existence. When Congress is not preoccupied with Kindergarten-level spats over debt ceilings that arrangement works almost tolerably well—a hurricane in the Gulf leads to Treasury spending to relieve the pain. A national economic disaster generates a Federal budget deficit of 5 or 10 percent of GDP to relieve pain.

That cannot happen in Euroland, where the Euro Parliament’s budget is less than one percentof GDP. The first serious Euro-wide financial crisis would expose the flaws.And it did.

Member states became much like US states, but with two keydifferences. First, while US states can and do rely on fiscal transfers fromWashington—which controls a budget equal to more than a fifth of US GDP—EMUmember states got an underfunded European Parliament with a total budget ofless than 1% of Europe’s GDP. (To make it even worse, the Parliament’s fundingcomes from the member states!)

This meant that member states were responsible for dealingnot only with the routine expenditures on social welfare (health care,retirement, poverty relief) but also had to rise to the challenge of economicand financial crises.

The second difference is that Maastricht criteria were far too lax—permitting outrageously high budget deficits and government debt ratios. Most of the critics had always (wrongly) argued that the Maastricht criteria were too tight—prohibiting member states from adding enough aggregate demand to keep their economies humming along at full employment. It is true that government spending was chronically too low across Europe as evidenced by chronically high unemployment and rotten growth in most places. But since these states were essentially spending and borrowing a foreign currency—the Euro—the Maastricht criteria permitted deficits and debts that were inappropriate.

Let us take a look at US states. All but two have balanced budget requirements—written into state constitutions—and all of them are disciplined by markets to submit balanced budgets. When a state finishes the year with a deficit, it faces a credit downgrade by our good friends the credit ratings agencies. (Yes, the same folks who thought that bundles of trash mortgages ought to be rated AAA—but that is not the topic today.) That would cause interest rates paid by states on their bonds to rise, raising budget deficits and fueling a vicious cycle of downgrades, rate hikes and burgeoning deficits. So a mixture of austerity, default on debt, and Federal government fiscal transfers keeps US state budget deficits low.

(Yes, I know that right now many states are facing Armageddon—especially California—as the global crisis has crashed revenues and caused deficits to explode. This is not an exception but rather demonstrates my argument.)

The following table shows the debt ratios of a selection ofUS states. Note that none of them even reaches 20% of GDP, less than a third of the Maastricht criteria.

| Alaska | 15.7 | Montana | 12.2 |

| Connecticut | 12.1 | New Hampshire | 13.0 |

| Hawaii | 12.2 | New York | 10.5 |

| Maine | 11.0 | Rhode Island | 16.9 |

| Massachusetts | 16.5 | Vermont | 12.6 |

By contrast, Euro states had much higher debt ratios—with only Ireland coming close to the low ratios we find among US states (the red line is drawn at the Maastricht criterion of 60%).

To be clear, none of these debt ratios would be too high for a sovereign government that issues its own currency. Remember that Japan’sgovernment debt ratio is 200%–and its interest rate has been close to zero for two decades. But they are too high for nonsovereign nations that use a foreign currency.

Those who follow Modern Money Theory believed that market “discipline” would eventually impose debt and deficit limits far below Maastricht criteria—to ratios closer to those imposed on US states. And with nofiscal authority in the center to match the US Treasury, the first serious economic or financial crisis would expose the flaws of the design of the euro. Because the crisis would cause member state deficits and debts to grow. At the same time markets would begin to realize that these member states are much like US states but without the backstop of a European Treasury. And that is precisely what has happened.

To be sure markets have not reacted simultaneously against all member states. If you think about it, this makes sense. There is a desire to hold euro-denominated debt—the euro is a strong currency and much of the world wants to buy European exports. So markets run out of Greece and Ireland and now Italy but need to get into other euro debt. Since Germany is the strongest member and by far the biggest exporter, it benefits the most from a run against the periphery.

Yet as Germany is a net exporter with a relatively small budget deficit, it is hard to get German debt. The biggest issuer of debt was Italy, and there was a strong belief in markets that because Italy’s debt is so large, it is like a Bank of America—too big to fail. And ditto for France and Spain. So spreads widened for Greece and Ireland and Portugal, but have only recently increased for Spain and Italy.

But after the agreement to accept a “voluntary” haircut of 50% on Greek debt, no prudent investor can any longer pretend that Italy, Spain or even France and Germany is a safe bet. Faith based investing in Euro debt is over. And note that if the stronger nations really do bail-out a Spain or an Italy, our friendly credit rating agencies will quickly downgrade the strong nations (they are now threatening France) for contributing funds to rescue their neighbors. Even Germany will not be safe if it participates in a bailout of Italy by committing funds.

There is thus a damned-if-you-do and damned-if-you-don’t dilemma. A bail-out by member states threatens the EMU by burdening and eventually bringing down the strong states; and allowing too-big-to-fail Italy to default would prove to markets that no member state is safe.

And this is why it does not matter how much the ECB lends to Eurobanks—the banks would be crazy to buy up government debt. And it is hard to believe that any US money managers can make a case that it is still prudent to invest in euro debt.

Many critics of the EMU have long blamed the ECB for sluggish growth, especially on the periphery. The argument is that it kept interest rates too high for full employment to be achieved. I have always thought that was wrong—not because I do not agree that lower interest rates are desirable, but because even with the best-run central bank, the real problem in the set-up was fiscal policy constraints. Indeed, several years ago, Claudio Sardoni and I demonstrated that the ECB’s policy was not significantly tighter than the Fed’s—but US economic performance was consistently better. The difference was fiscal policy—with Washington commanding a budget that was more than 20% of GDP, and usually running a budget deficit of several percent of GDP. By contrast, the EU Parliament’s budget could never run deficits like that. Individual nations tried to fill the gap with deficits by their own governments, these created the problems we see today—as the chickens came home to roost, so to speak.

Is There Any Solution?

Once the EMU weakness is understood, it is not hard to see the solutions. These include ramping up fiscal policy space of the EUparliament—say, increasing its budget to 15% of GDP with a capacity to issue debt. Whether the spending decisions should be centralized is a political matter—funds could simply be transferred to individual states on a per capita basis.

It can also be done by the ECB: change the rules so that theECB can buy, say, an amount equal to 6% of Euroland GDP each year in the form of government debt issued by EMU members. As buyer it can set the interest rate—might be best to mandate that at the ECB’s overnight interest rate target or some mark-up above that. Again, the allocation would be on a per capita basis across the members. Note that this is similar to the blue bond, red bond proposal discussed above. Individual members could continue to also issue bonds to markets, so they could exceed the debt issue that is bought by the ECB—much as US states do issue bonds.

One can conceive of variations on this theme, such as creation of some EMU-wide funding authority backed by the ECB that issues debt to buy government debt from individual nations—again, along the lines of the blue bond proposal. What is essential, however, is that the backing comes from the center—the ECB or the EU stands behind the debt.

No amount of faith in the European integration is going to hide the flaws any longer. A comprehensive rescue by the ECB—which must stand ready to buy ALL member state debt at a price to ensure debt service costs below 3%–plus the creation of a central fiscal mechanism of a size appropriate to the needs of the European Union is the only way out. If these actions are not taken—and soon—the only option left is to dissolve the Union.

So, finally, returning to the “one nation-one currency” rule would allow each nation to recapture domestic policy space by returning to its own currency. There was never a strong argument for adopting the Euro, and the weaknesses have been exposed. Currency union without fiscal union was a mistake.