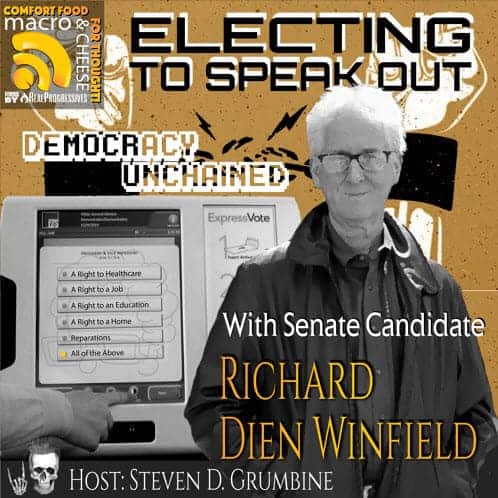

Episode 79 – Electing to Speak Out: Democracy Unchained with Senate Candidate Richard Dien Winfield

FOLLOW THE SHOW

Our guest is a US Senate candidate in Georgia. He talks to Steve about social rights, those rights that aren’t in the constitution but need to be, including the right to a job, housing, and education at all levels. He doesn’t just support M4A, he…

This week we welcome Richard Dien Winfield, a rare candidate for national office who is running on the Federal Job Guarantee and Medicare for All. It’s no surprise, then, that Richard is fully onboard with Modern Monetary Theory and spoke at the MMT Conference in Stonybrook last September. Steve talks with him about his new book, Democracy Unchained: How We Should Fulfill Our Social Rights and Save Self-Government, and the platform for his current campaign.

Richard is running in Georgia’s special election for the US Senate. His campaign is founded on correcting the failure to recognize and enforce our social rights, which he sees as the key to remedy blockages of opportunity that hobble our democracy. Throughout this interview, he frequently returns to the concept of social rights as the rights that are not in our constitution but should be. These include the right to a decent livelihood, healthcare, education at all levels, the right to balance work and family, and to level the playing field between employer and employee.

Martin Luther King said that without a job and income, one can have neither life, liberty, nor the opportunity to pursue happiness. Richard eloquently connects the dots between our social rights, demonstrating their interdependence. How can you solve homelessness without a job guarantee, which will require a higher minimum wage than the $15-an-hour we normally hear about. The job guarantee would, of course, include full benefits of pension and healthcare — though we wouldn’t need the latter if we had Medicare for All, which is another necessary social right: without health, we can’t exercise our freedoms.

There are two exacerbating factors disempowering employees. The first is globalization and free trade, due to the ease with which companies can find the lowest wages and relocate. The second factor is the rise of the gig economy. Employers can use technological advancements so that workers are on their own and scattered around the globe; the employer doesn’t have to provide overhead or face worker solidarity.

Richard describes the UBI as setting up a 2-tiered society: those condemned to the poverty income of the UBI alone, and those who receive the UBI plus wages from their jobs. Instead of eliminating economic disadvantage, it sanctions it.

Considering the threat of fascism, we look again to an FJG. For all the praise given to the social democracies of northern Europe, the fact that they don’t have a job guarantee has left them vulnerable to the kind of xenophobia and bigotry that has caused workers in other countries to vote for extreme right-wingers. When there aren’t enough jobs, a wave of immigrants is seen as a threat. Universal healthcare and generous unemployment insurance do not replace the need for jobs.

Richard and Steve go through all the social rights in depth and, sometimes, from a new angle. Listeners will hear something they might not have considered about racism, sexual harassment, unionization, corporate compensation, reparations, the needs of families, and much more. Have you ever heard a candidate demanding legal care for all? Listen to the episode!

Richard Dien Winfield is an American philosopher and Distinguished Research Professor of Philosophy at the University of Georgia. He has supported striking workers, organized sugarcane laborers, and joined unionizing efforts at UGA. Winfield was a candidate for U.S. Representative from Georgia’s 10th Congressional District in 2018 and has declared his candidacy for the 2020 United States Senate special election in Georgia.

WinfieldforSenate.com

@WinfieldForUS on Twitter

https://bookshop.org/books/democracy-unchained-how-we-should-fulfill-our-social-rights-and-save-self-government/9781950794133

Macro N Cheese Episode 79

Electing to Speak Out: Democracy Unchained with Senate Candidate Richard Dien Winfield

Richard Dien Winfield [music/intro] (00:00:04):

When we are in a global depression, this is absolutely the worst time to follow any path of austerity or to follow the advice of these deficit hawks. If you can’t put people in a decent dwelling, how can we shelter in place? How can we contain a pandemic? This is literally a matter, not just a human dignity, but of life and death.

Geoff Ginter [music/intro] (00:01:26):

Now let’s see if we can avoid the apocalypse altogether. Here’s another episode of Macro N Cheese with your host, Steve Grumbine.

Steve Grumbine (00:01:34):

All right. And this is Steve with Macro N Cheese. Today, we have Senate candidate, Richard Dien Winfield joining us. Richard is a philosopher. He’s an author, he’s a professor, he’s a union member. He’s a husband, father, you name it. He’s a lot of things. But one thing is, is a candidate struggling through a COVID-19 environment where he is trying to get his message out much the same way that Bernie Sanders was left to try and get his message out in the midst of a pandemic. It’s quite a challenge.

The other thing is that Richard being an author has got a really great book and part and parcel with the candidacy that he’s running is this wonderful book that one of our prior guests, Irami Osei-Frimpong had raised to us, which is Democracy Unchained: How We Should Fulfill Our Social Rights and Save Self-Government.

So it’s within that, that I thought, what better way to put this out there than to have Richard join us? And I’m very excited. I met Richard at, I guess it was the third modern monetary theory conference in Stony Brook University, where Stephanie Kelton teaches. And he gave a very impassioned riveting speech, which unfortunately my tech did not pick up. And so I needed to hear this again. So what I’ve done is I’ve got Richard joining now, and I gotta tell you just brace yourselves because this guy’s got some great ideas. And with that, welcome to the show, sir. How are you today?

Richard Dien Winfield (00:03:08):

I’m doing great. Thanks for having me. It’s a real pleasure to have an opportunity to discuss things at length.

Grumbine (00:03:14):

Absolutely. So tell me, you’re running for Senate. Talk to us about where you’re running and what the conditions of your candidacy are.

Winfield (00:03:23):

Yeah, I’m running in what is being called a jungle election. It’s a special election to fill out the seat that the Republican incumbent Johnny Isakson had vacated owing to illness. And the Republican governor Kemp had nominated as an interim, the notorious Kelly Leffler, but there is an election taking place on November 3rd with no preceding primary with 20 candidates from all over the political spectrum, going at it with a very likely runoff.

So it’s a race that is operating to some degree in the shadow of another Senate race of Georgia, which had a regular primary. It was John Ossoff won on the democratic side to face the Republican incumbent. And our race sort of, as I mentioned, not had much of a chance to gain much sunshine because we really got underway right when the pandemic hit and while in-person campaigning was suspended.

And that’s a huge problem for candidates like myself who are not the darlings of the political establishment. We’re not showered with media attention and big contributions. So it was very challenging. It’s very difficult, especially since the organizations that would have been sponsoring in-person candidate forums are just beginning to put out some zoom meetings, which unfortunately have rather limited audiences.

Grumbine (00:04:42):

Sure. I appreciate that. I guess it’s with that, I’m typically not interested in the races so much because nine times out of 10, these things are platitudes, but you’ve been at this for a while. I remember Joe Firestone talking to you about the federal job guarantee and we were all shocked that there was an actual candidate running on a job guarantee platform.

And then to see this book that you’ve written and folks it’s available on Kindle for free, if you’re a subscriber, but it’s only $4 and 95 cents, I think. So definitely take a look at this book, but this book is kind of a roadmap, if you will, for not only how you view the world and what a candidate Richard might look like, but in general, this has been described as a blueprint for progressives to follow, to change our society the way we claim we want to change it. Can you tell us a little bit about the book?

Winfield (00:05:39):

Yeah. I mean, the book in a way grew out of a campaign that I ran two years ago when I ran in the 10th congressional district in Georgia in 2018, as what the nation called the first candidate to advocate a federal job guarantee. And my campaign then is very much what is today. I was advocating what I think is the key to really remedying the blockages of opportunity that hobble our democracy and these revolve around our failure to recognize and enforce our social rights, the rights that are not in our constitution, but should be.

The rights to a decent livelihood, a right to healthcare, right to livelihood, right to education at all levels, right to balance work and family, right to level the playing field between employer and employee, rights to legal representation in all forms of cases. These are the kinds of rights that we ignore and in doing so, we allow oppression in the household and in society to really bar our ability to interact as self-governing citizens. And now we are obviously in a real time of reckoning where the health crisis and the accompany economic crisis and the racial justice crisis are all shouting for a remedy as a matter of survival. And that remedy consists in this job guarantee, social rights agenda.

Grumbine (00:07:07):

Very powerful. This commission, this task force, if you will, that was put together by Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders. You had Stephanie Kelton, you had Darrick Hamilton, you had Sara Nelson of the airline attendants union. And they tried to put a federal job guarantee out there and it was rejected outright, and it was rejected on the basis that number one, they didn’t even really know what it was, but number two, it didn’t really jive with what they wanted to do, which for a progressive feels rather appalling actually.

I want to dive in because you don’t waste any time. You start right off the bat with chapter one being universal basic income versus guaranteed employment, why we need a federal job guarantee and let’s just start right there for everyone. I mean, I want people to really understand the job guarantee. We had Pavlina on, who’s an eloquent speaker on the subject, but you’re running a campaign on this. What does that mean? Why are you so pro job guarantee and what does it have to do with the UBI?

Winfield (00:08:12):

Yeah, well, to begin with, I think Martin Luther King actually hit the nail on the head when he said in his last year of life, that without a job and income, one has not a life, liberty nor the opportunity to pursue happiness. To be able to have a decent livelihood is the very foundation of being in a position to exercise any of one’s freedoms. And it’s important to understand why guaranteed jobs at a fair income are the ground zero of economic independence.

We all know that in a market, there are other ways of earning a living. One can opt to try to be an entrepreneurial landlord. But I think we know all of us that if you fail in either of those endeavors, you are left having to rely upon the one thing that we all have in a properly civil society. That is where we are all persons where no one is a slave. Namely, we have ownership of our labor power, and that allows us to earn a living provided there are jobs.

Now the other side of it is that in any market society, it turns out, for a reason I want to explain, that the overwhelming majority of individuals of bread winners have to earn a living as employees. And the reason is that a logic of competition compels enterprises to grow and consolidate in order to be competitive, which means it is impossible, economically speaking, for everyone to be an entrepreneur for small business to be the real foundation of the economy.

Instead you have this polarization inevitably between on the one hand, a very comparatively small number of enterprises and a much larger group of people seeking a livelihood as employees. And the only way employment can be guaranteed is if the federal government steps in to deal with the inherent failures of the market to provide full employment.

And that’s what a federal job guarantee does. The government steps in and will provide jobs to anyone who’s willing and able to work, but cannot find employment in the market. And we know that there are people for centuries who have been pointing out that there could be a problem in relying upon public sector employment, cable races is problem.

We might even say Rosa Luxemburg does any accumulation of capital by saying that in effect, any attempt to provide employment through the public sector will only in a sense undermine the opportunities of the private sector to provide unemployment. We’ll be competing with the private sector. But clearly that is not the case if the jobs that are offered by the federal government are jobs that provide goods and services the market is not offering.

And these have to do with all the various public goods that are not able to be, let’s say monetized, all the types of infrastructure, things that are required for us to prosper and all of the human services that are needed that are not being provided by the marketplace.

And that’s in a way, what opens the door for there to actually be an achievement of full employment. And it’s important to see what that accomplishes and what are the two things that have to be tied to it because one thing one has to keep in mind and when one speaks about a federal job guarantee, it’s not just a matter of eliminating once and for all unemployment, but also eliminating poverty income.

And the way that is achieved is by two things that I think are a crucial element of a federal job guarantee. On the one hand, it has to pay a fair wage, not a poverty wage and a fair wage has two components. And I think I hear them going beyond many proposals that are made in behalf of the federal job guarantee. Many of the proponents stick to the idea of a living wage calibrated at $15 an hour, but the two problems with a living wage of $15 an hour.

First of all, it’s a poverty wage according to the government’s own statistics. No one in any American city can afford decent housing and have sufficient residual income on $15 an hour. Moreover, it does nothing to prevent the advance of income and ultimately wealth inequality. And to remedy both of these problems, one has to have attached to a federal job guarantee, a new fair minimum wage that starts at at least $20 an hour, and as adjusted both with inflation and with national productivity gains.

So that in a way you could say all boats rise with the increasing prosperity of the nation. And in order for this to wipe out poverty income at large, it has to be connected with an equivalent replacement income for those who cannot work. In other words, we have to increase the benefits to the disabled and retirees to the level of a fair minimum wage, which I think should start at at least 20, we’re talking about $41,600 a year. That’s far beyond what social security offers people who are disabled or retirees, who on average receive, you know, the $1,200 a month for the disabled and $1,400 a month for the retired.

Grumbine (00:13:24):

Would you suggest that you are in favor of expanding social security? Is that what I’m hearing? You’re not talking about a separate program, are you? Are you just talking about changing some of the requirements on social security, expanding those options and raising the pay level? Or are you talking about standing up a totally separate structure for this?

Winfield (00:13:44):

Well, what I don’t like about the social security system beyond the levels of compensation it provides is that it finances itself through payroll taxes to a large extent. And I think payroll taxes in general are a bad way of making public investment. They’re kind of an invitation as Randall Wray pointed out, to replacing workers with robots who don’t have to pay payroll taxes.

So I think instead we need to basically fund these kinds of social guarantees at a proper level, wipe out poverty income across the board, which of course together with a federal job guarantee that wipes out poverty wages and unemployment produces in a sense the steady maximum consumer demand. That of course is good for economic growth in general. It also eliminates the fear of firing which plays so important a role, in a sense, making it difficult for people to stand up for their rights on the job.

Again, sexual harassment, racial discrimination, employer malfeasance of any sort of course that fear of firing is most extreme in the United States. Because on the one hand, we have a complete disempowerment of labor where unionization has fallen to no more than 6% in the private sector. So for nine out of 10 workers at a minimum, you face a situation where you can be fired at will.

And for many, if you’re fired, you lose health insurance, which unfortunately is tied to work in many situations as well as pension benefits. And that of course means you not only lose income, but you lose your ability to have any kind of access to healthcare. So the federal job guarantee has very important features regarding all sorts of our rights and note that when I’m speaking about a fair minimum wage, it’s much, much higher than a basic income.

Basic income is proposed by all sorts of UBI enthusiasts from Yang to Milton Friedman, to all the people who’ve been doing this for almost a century. It is basically a poverty income. It sets up a two tiered society where you have those who are condemned to the poverty of a basic income, and those who receive the basic income plus the wages they receive, we’re actually participating in the creation of wealth.

So instead of in a sense, eliminating economic disadvantage, UBI sanctions, and enforces economic disadvantage by separating society into those who just have UBI. And those are the UBI with the responsibility of generating the wealth, which will support UBI. And it also leaves one in effect, devoid of the freedom that is alleged to provide, because what resources do you have on UBI? You barely have enough to satisfy your biological requirements. You have nothing left to engage in all the other kinds of activities that require any sort of capital. You’re left with this premature hobby existence, in other words, a premature retirement.

Grumbine (00:16:48):

Let me interject on that because one of the things I think that is oftentimes missed by UBI enthusiasts, who don’t get what you’re saying is the fact that the goods and services that they would have to purchase with those dollars. Okay. There’s nothing there to ensure that the economy even exists by just giving you cash. There’s no guarantee that the goods and services that they need, not just that they want, but they need will even be there at the price in which they get them.

Winfield (00:17:18):

Exactly.

Grumbine (00:17:19):

There’s nothing there to peg the cost of goods sold to the UBI. And I think that that’s a real serious issue in terms of a price anchor. What are your thoughts on that?

Winfield (00:17:29):

No, I agree that it leaves completely up for grabs whether or not what one receives, will not only allow you to feed yourself and clothe yourself, but whether you will have a roof over your heads, access to medical care, to education, to anything else, as well as any kind of meaningful activity, which goes beyond a hobby, but something that involves engaging with others in activities that you could say contribute to the wellbeing of society.

You’re left in a purely private existence with minimal resources and basically living with a kind of insecurity. You know, the claim is that, well, this is going to relieve you of economic insecurity, but as you point out, it does not. It says nothing about whether the UBI will be sufficient to provide you with a sufficient supply of what you would need at prices you can afford. So I think it is very questionable to say the least as a remedy, whereas by contrast, the federal job guarantee provides everyone with a fair income.

If one associates with it, not only a fair minimum income, but fair replacement income for those who are not able to work. And at the same time, it provides all the benefits, the anti cyclical benefits of full employment. By again, providing we could call it a reserve army of the employed who have money in their pockets. And that allows us to avoid the kind of catastrophes we’re undergoing right now.

Grumbine (00:18:55):

I like that.

Winfield (00:18:55):

With a huge surge in joblessness and the accompanying lack of money. We’re in this desperate surge to open businesses. Well, what do we find? Not only are people scared to go to businesses because their safety is not provided for, but they’re broke. They don’t have money to spend. If we instituted the federal job guarantee, that would not be an issue.

Grumbine (00:19:17):

Indeed. And you know, one of the things that I find fascinating, and you brought this up just now very well, which is a great segue to the second chapter of your book. I should say the third chapter of your book, which is healthcare. We’re in the middle of a pandemic. And we’re realizing what tying healthcare to employment does in the midst of a global depression, as millions are being let off the payrolls, they’ve got no prayer for better. Let’s segue into healthcare as a right. Describe what you mean there.

Winfield (00:19:49):

Now I think in a way there are two types of health broadly speaking that are right, precisely because you can’t exercise any of your freedoms, if you don’t have this kind of health available to you. First of all, there’s the health of the environment. And I’m referring specifically to the huge degradation of the environment and the advance of climate change that is bearing down on us. That’s not on holiday right now, and that is going to make it very difficult for us to engage in any of the activities in which we can exercise our freedom, be it in society or in politics.

So that’s one thing to which we have a right. We have a right to a livable environment, which provides us with sufficient opportunity to exercise our various freedoms. But then there’s also our own personal health. If we don’t have our health and equal access to it, we are underprivileged in the sense that we don’t have what we need to be able to engage in any kind of activity. And we’re referring to, of course, not just physical health, but mental health. We have to have access to all of that plus long term care and the like.

You know, we’ve seen every developed nation find a way of fulfilling that right to healthcare by, in every case, getting rid of a for profit private insurance industry. Now there are three broad avenues that have been pursued. One is a national health service, which Great Britain opted for it in 1948, and they actually have ended up with the lowest cost per person in sense, fulfilling the right to health care.

And that’s an option where in a sense, the government has more or less nationalized healthcare and all of its operations are by and large employers of the state sort of like making veteran’s hospitals, our universal model. Then on the other hand, you have a single payer system, which is what those who support Medicare for all, such as myself, we’re advocating. That has actually been followed by very few nations in the world.

You have Canada. And of course, as we all know, you have Taiwan, but very few, few others. And then as another, your option, which is pursued by far more nations is you have a highly regulated public health insurance system with multiple plans. All of them are nonprofit and provide comparable services. People required to operate and subsidies are given. So it’s affordable to all.

I think in America, the best route, the easiest route, as well as the most affordable route is Medicare for all, for the following reasons. First of all, you don’t have to engage in any kind of public investment to take over healthcare practitioners and pharmaceutical companies and the rest. You’re simply providing a national health insurance policy, a single payer system. You leave in place health care providers, pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, and the like.

Secondly, we already have an apparatus at hand in Medicare and Medicaid where we have a public health insurance system, which actually has far fewer operating costs than any of the private alternatives for obvious reasons, And that can be expanded. And that way we can do it, I think immediately in a matter of months, not in terms of years as Bernie Sanders proposed, but really doing it all at once.

Just like the British introduced their national health plan within months, I think we can easily provide Medicare for all. In fact, right now we should be offering full Medicare coverage of any uninsured health cost of anyone in this pandemic. And then we make it a permanent solution with Medicare for all, meaning no copays, no deductibles, no premiums.

Grumbine (00:23:26):

I like that.

Winfield (00:23:27):

You know, and we have four advantages for this kind of system. First of all, everyone has the same coverage. So it’s fair, unlike other systems. Secondly, you have complete freedom in going to any health practitioner you want to, unlike private insurance scheme. Thirdly, it gets rid of all the overhead of private insurance with first of all, we don’t have the super salaries of CEOs or the dividends to private investors.

We don’t need any advertising costs. We don’t need all the ridiculous overhead of processing a proliferation of competing plans. All of that is eliminated. And then finally we’re in the strongest position to keep healthcare costs in line with other nations and cut them in half because we can negotiate as one for what the prices should be for pharmaceuticals, for care and services of all sorts. And that way we can actually reduce costs in half, say $1.7 trillion a year. I think that’s the road to go, right?

Grumbine (00:24:29):

Yeah, but I think that there’s a way to come back to this. So I’m going to do it. Your second chapter actually was on employee empowerment and the elimination of class advantage and having healthcare tied to employment is a bad deal when your employment is not guaranteed, but when you have a job guarantee, which we just talked about and you have a healthcare system, as you’re describing, how does that employee empowerment and elimination of a class advantage happen? What is your vision there?

Winfield (00:25:00):

I mean, first of all, I think we have to take seriously the ramifications of the dynamic of competition in markets, which is what, in a sense makes the polarization between employer and employee the key relationship around which economic justice revolves because firms are required to grow and consolidate. And that means that the relation between employer and employee is unbalanced in favor of the employer, because there are far fewer employers, they have much more economic power than individual employees and they have much more options.

So that lack of balance has to be remedied. And I think there are two fundamental ways of doing it. One of course is to ensure that at every workplace with multiple employees, including gig economy employees, we have unionization and the current form of unionization under the Wagner Act, it has proven to be unsuccessful. You know, now, as I mentioned earlier, the rate of unionization has dropped to 6% in the private sector. It’s above 10 in a public sector.

But what that means is overall employees face employers in total isolation. And this is being exacerbated by two other developments that are racing along and generally disempowering employees. One of course is globalization and free trade policies, which make it easier than ever for enterprises to relocate operations, where they can find the lowest common denominator in wages and other ways of avoiding costs that should be born.

And secondly, with the rise of the gig economy, where employers can avail themselves of technology to have people work 24 seven, anywhere in the world, without having to put up the kind of overhead of a place of work for them and to escape the difficulties an employer faces and having to deal with a solidarity of employees.

So for that reason, I think we need to transform the dynamic of unionization and make it automatic. We should have automatic elections for union representation in every enterprise that has multiple employers. And that includes Uber and any of the gig economy enterprises. And you have the elections. You want to participate. You participate, if you don’t, you don’t, but someone will be elected as your representative. And they will engage in collective bargaining, have the right to strike.

On the other hand, we need to have another transformation from within of corporations and corporations are the dominant form of enterprise because every enterprise must seek as much capital as it can. And the public share issue incorporation allows enterprises to gain capital from anywhere in the world without having to pay any costs of borrowing. And that is the dominant form.

Inevitably, if the market is left to its own designs, but that imposes a kind of tyranny of corporate boards, who are controlling the course of what an enterprise does needless to say to the disadvantage of consumers and employees alike. And we can remedy this by doing what was first introduced in Germany, the Weimar Republic, and afterwards after World War II and many European countries having what’s called worker code determination, where basically you set aside half the seats on my scheme, which I think is the fair way to go, half the seats go to the elected representatives of employees.

That way we can put an end to the super salaries of CEOs. We can put an end of the dismemberment of corporations to enhance the value of the stock portfolios of investors. We can put the brakes on the transfer of operations to other places at lower wages. We can ensure that corporations are going to respect the environment and the community. I think these two measures would fundamentally transform from within the way in which enterprises operate, and also allow there to be a much fair distribution of income and wealth in this nation.

Grumbine (00:28:56):

That’s incredibly powerful. I think that all of us that are fighting within this progressive space have ideas about this. And you have given a very clear step by step approach to this, which I think will satisfy a great many people’s need for ideas and information. One of the things that jumps out at me though is the next subject in your book, which is the balancing of work and family. And I want to take a crack at editorializing momentarily, and then let you respond.

One of the big things that stands out to me is the inability to participate in democracy even because of the overwhelming burdens that employment puts on us, whether it be for watching we say on social media, to whether it be not being able to take off to go vote because voting is not a national holiday, but in general work has overtaken our ability to coach our kids sporting clubs.

It has really robbed us of the ability to participate in more than just our family to have life outside of the workplace. The COVID-19 situation has allowed a great many people to either a- work remotely or b- has pulled them completely out of the workplace altogether and has created some very strange family dynamics and so forth being in quarantine. But your idea here about balancing work and family, I think is very important. Can you explain what your angle is? And maybe talk a little bit in terms of the things I raised there as well?

Winfield (00:30:33):

Yeah. I think a very important angle related to balancing work and family is the nature of systemic gender disadvantage because you know, for 50 years has been a bill calling for equal pay for equal work. Thanks to Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s litigation. The equal protection clause in the 14th amendment has more or less been extended to gender doing what an equal rights amendment would have done if it had been passed, but still there remains this gap in wealth and income between men and women, you know, women in the U S makes four fifths of what men do.

Women have one third the wealth of men. Women are the ones who are the heads of single parent families by 83%. They do three quarters of the care for elders in a family. So all of these things mean it can be no surprise. Why women, despite all of the successes of the women’s movement have not been able to take their fair share of income, wealth, and power as a position, both in the economy and in politics.

Balancing work and family is in a sense, something essential if we’re going to overcome gender disadvantage. And what we’re talking about are several key things. You know, we need to have paid leave, paid leave, not only for matters of health, but also for matters of family. You know, you need to have paid leave so you can go to a school conference. You need to have paid leave of at least nine months when a newborn is coming into the world. You need to have paid leave when you have to go to court because of a family member who you have to be with.

There are many circumstances in which you need to have paid leave so that you do not suffer economically because of your family duties. We also need to do something that they do in every country in the European union, have a one month paid vacation mandated for everyone. So you have time to stay with your family. Of course, we need to think about reducing the workweek or at least keeping it at 40 hours.

Many people in America, as we all know are working two or three jobs because of poverty wages, because of lack of union representation. Also, we allow something in this country that no other developed nation allows, which is we allow for mandatory overtime, where at any moment, your employer can demand that you not go back to your family for dinner or some event, but stay at work. We have to abolish that as other nations have.

But in addition, we have to have free public child and elder care, which is an incredible burden for people and makes it impossible for a parent or caregiver of any gender, but particularly women, to be able to exercise their economic and political freedoms. And in addition, we need to have a $900 monthly child allowance because that’s what the government says you need to have to cover the added expenses of having a child.

And these things by the way, are crucial to achieve genuine reproductive freedom because reproductive freedom is not just a matter of having the right to an abortion and having Medicare for all funding abortions, as well as any kind of birth control measures in the like. But you need to be able to afford the children you want to have.

You’re going to have genuine reproductive freedom, and you have that, thanks to at least in large part, a federal job guarantee, fair minimum wage, having child allowances, having paid leave that allows parents and women in particular to not need any abortions, frankly. I think this is the death knell of the argument made by the pro life contingent, who in banning abortion, are just driving it underground and adding to the list of casualties of the women will suffer by going under the table for substandard medical care.

And this way you actually reduce abortions to a humanly possible minimum when you make it possible for people to have all the care they need with regard to reproductive health and be able to afford whatever children they want. And that is something that is a real emancipatory power. Now there’s one other thing you mentioned, which has to do with political freedom. And I just want to bring up something that has to do with my situation as a state employee. As a state employee, I was required in 2018 when I ran for Congress and I am required now to go on unpaid leave if I run for office.

Grumbine (00:34:48):

Wow!

Winfield (00:34:48):

Now an employee has three strikes against him or herself in running for office because the way things operate in this country. If it’s a serious race where you have to devote your time to the campaign, that means you have to stop working and have no income first of all.

Secondly, you no longer get the benefits, which in our country, alas, involve health care and pension benefits. And thirdly, for most people, your job will not be waiting for you if you lose the campaign. I don’t have that problem because I’m a tenured professor. I can get my job back, but we have to think about a kind of campaign finance reform that deals with this small money problem, namely, we need to guarantee everyone who runs for office replacement income for the duration of the race.

They have to retain whatever benefits they have and they have to have guaranteed a job, the same job waiting for them at the end of the race if they lose. Then we can allow 95% of our breadwinners to actually have the right to run for office because they don’t have the right to run for office now. We know who fills our legislative bodies. Yet, there are people who have, you know, independent occupations, lawyers, doctors, business, people where they’re independently wealthy.

Grumbine (00:36:06):

Absolutely.

Winfield (00:36:07):

That’s part of the oligarchy that prevailed in our country.

Intermission (00:36:21):

[music] You are listening to Macro N Cheese, a podcast brought to you by Real Progressives, a nonprofit organization dedicated to teaching the masses about MMT or modern monetary theory. Please help our efforts and become a monthly donor at PayPal or Patreon, like and follow our pages on Facebook and YouTube and follow us on Periscope, Twitter, and Instagram. [music]

Grumbine (00:37:10):

One of the other things we talk about. We may say we have a right to freedom, but without guaranteeing a host of other things, the freedom we talk about is rather hollow. And one of those things is the right to decent housing, which is your next chapter in your book.

Winfield (00:37:28):

Yeah. Yeah.

Grumbine (00:37:28):

I often think of rights and I ask myself, how is this enforceable? How can we make sure that is a right of right if you can’t enforce it? But this housing was brought up, Bernie Sanders raised it in his campaign, as well as a fundamental right to housing. What does that mean to you? And what are you describing in your book?

Winfield (00:37:49):

Now, first of all, if we talk about a fundamental right to housing, we have to understand we’re talking about housing that is decent enough to enable a person to exercise all of their freedoms, which means it has to be a house that’s large enough and sufficiently equipped so that you can engage in all your activities.

And if you have a family to properly treat your spouse and children and have what you need, which today requires all the utilities that are required and broadband, which we see is absolutely crucial, especially in times of pandemic, because how can you do any kind of remote learning or work if you don’t have access to broadband, which is not available to millions, tens of millions of Americans. So that’s part of the right to housing.

And what really makes it feasible is the fact that we have a right to a livelihood that is enforced by federal job guarantee and fair wages and replacement income. It goes with that available as well as of course, Medicare for all, which means that you have care for your physical and mental difficulties and will allow you to maintain a house and stay in a house, including home care.

They were in a position where we can have a permanent ban on evictions, foreclosures and utility cutoffs, because we can always have mandatory repayment rescheduling, because everyone will have a stream of income. And we can use the federal job guarantee to ensure that there is a sufficient supply of adequate housing, because that’s the other side of it. We have to ensure that there is an adequate supply.

And we also have to think of, of course, keeping both rents and mortgage payments in line so that they’re affordable. You know, there’s a lot of talk of how now more than ever people are rent burdened, mortgage burden, rents, and mortgage payments are rising much higher than incomes or inflation. Something has to be done to keep them affordable.

You know, we can have national rent stabilization, but we also have to have an adequate supply of housing. We can also have a stabilization of mortgage payments as well and have the kind of mortgage insurance that no longer discriminates as it used to, but we also have to ensure that there’s adequate public housing. And we can use that as a way of rethinking how we want to have our communities developed.

Grumbine (00:40:10):

Can I stop you? I’m so riveted, if you will, by the fight on gentrification. Gentrification seems to rob us of that affordable housing. And it really takes housing that is rundown and terrible. And this goes to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s really phenomenal book. She recently wrote regarding post redlining America and how predatory inclusion allowed these people to have access to houses suddenly.

And they were buying houses that were rundown that were ready to be condemned. They had rats and horrible situations, and then they were stuck on the line for the debt. But then when the bank would foreclose, there was no loss for them because they were insured against it. And then they’d resell it again. Sure. What would stand in the way of this predatory inclusion as we pursue a right to a home and what would prevent gentrification with your concept here?

Winfield (00:41:08):

Well, I think that there are always several sides. There really three principle sides to the housing crisis. One is the fact that people don’t have sufficient income to either stay in their houses or to be able to either rent or buy decent housing. Secondly, they don’t have the healthcare they need to allow them to function and maintain a dwelling. And then thirdly, there’s not necessarily an adequate supply of decent housing.

Now the federal job guarantee can deal with two of these problems. That is a can provide people with a sufficient income, provided we have a sufficient supply, which a federal job guarantee can also put people to work, not only building houses in a way that in a way gives us an architecture of freedom, a democratic architecture that would involve a lot more walkable spaces, that foster community that do not segregate people by race or class or age, et cetera, but then also it will with Medicare for all, ensure that people have the healthcare, mental health care they need. So these are important keys to the puzzle, but I think we have to recognize, you know, there are 30 million dwellings in America that are substandard. These need to be immediately fixed up or replaced.

The federal job guarantee, you can put people to work doing this. We need to make the public investment in that. We need to also think of a sufficient supply of public housing. They would no longer warehouse the poor because we will no longer have poor people, if we have a federal job guarantee and proper replacement income and fair income and fair wages minimum, as well as employee empowerment. You know, we would have a completely different kind of population with completely different kinds of opportunities and the ability to maintain things.

And then public housing takes on a completely different character. In Sweden, for example, public housing is not something that warehouses the poor, involves people of all income levels and that’s how it should be. And I think we can completely transform our housing crisis and eliminate the vile shameful practice of allowing there to be homelessness. And today 30 million households have been unable to pay their rent or mortgages in this coming month, which means more than a hundred million people are facing homelessness. And we have to step up and do something ASAP.

Grumbine (00:43:26):

Let me ask you. Everywhere I go, and it’s been a while since I’ve been out and about, because I pretty much am tethered to the house right now, as most of us are. Sure. But everywhere I go, there are empty malls, malls all over the place. Strip malls, big malls, malls, malls, malls. Why have these not been turned into public housing? Why have they not been turned into places with solar panels on the roofs of them? Why have the parking lots not been transformed into energy centers where we can make those solar highways? Bottom line is why haven’t we done with what we have? Is there a capital investment there that is blocking a public investment? Or what is the gap there? That just makes no sense to me.

Winfield (00:44:14):

Yeah. I mean, I think the big gap is to not have a public commitment to fulfill the right to decent housing. And if you have that commitment, then you are going to give a decent dwelling to anyone who needs it. And you’re going to make the public investment to do that and put people to work. To provide by either converting empty places into livable dwellings, or build them anew.

And it’s a matter really of recognizing this as a right and rights are not negotiable. You fulfill them. And if someone has a right to public housing, you recognize it. Homelessness is a wrong, and FEMA should immediately be providing at the most temporary housing with broadband and a kitchen and utilities and so forth to anyone who is homeless. And that should be regarded as something that has to be done as part of a national emergency.

We had this national emergency before the pandemic where every night 550,000 people were trudging around with no place to stay and a million and a half people experiencing the trauma of homelessness. Well, now that has grown astronomically and that should be a wake up call. And of course, if you can’t put people in a decent dwelling, how can we shelter in place? How can we contain a pandemic? This is literally a matter, not just of human indignity, but of life and death.

Grumbine (00:45:35):

Yeah. This is a public safety concern. Isn’t it?

Winfield (00:45:37):

Exactly. Exactly.

Grumbine (00:45:40):

One thing you brought up, I want to state this. I have a friend that is a homeless activist in Indiana, who is finding not only are they closing down tent cities, but they’re not providing temporary shelter. And these people are literally COVID-19, they’re infected and they’re out in the streets with no one to take care of them, no shelter, no food, no nothing. And they’re left to forage and scavenge around under a pandemic empirically happening right now. That’s insane!

Winfield (00:46:12):

I mean, that’s why we, as a nation are the least prepared to contain the pandemic and our failure to do so reflects not only in a way, the incompetence and criminal negligence of our leadership, but also the fact that we have failed to implement these social rights. That was not the creation of Donald Trump. It was already at hand under his democratic predecessors and we are now reaping the disastrous consequences of that failure.

Grumbine (00:46:41):

I was in a debate earlier with a very good friend and it really got down to brass tacks and it was pretty painful because this is someone I care deeply about. And I think they care deeply for me as well. And it came down to I can’t support fascism and from the Patriot Act to any number of very tough on crime things. The democratic candidate has exhibited fascist qualities, as well as the maniac in power today. Which way do you turn?

I can’t vote for a fascist. And so that leaves me in a very difficult place, but I liken this to playing football. I’m not going to play offense if my quarterback is Ryan Leaf. I’m going to lean on my defense because I’ve got a world champion defense and they say defense wins championships. At sometimes it seems like the right move is to punt. It isn’t always to try and jump on offense when you don’t have the right quarterback or you’re missing your top receiver. I don’t quite understand what the play is here when you’ve got bad and bad. There doesn’t seem to be anyone with a light bulb of brains or whether it be just inspiration to serve the people. I just don’t get it. How do we end up here?

Winfield (00:47:54):

I mean, I really think what has contributed to the growth of fascism in the United States and in every other developed nation is really the failure to fulfill the right to work with a job guarantee. And you see this in all of the nations in for example, Northern Europe that have universal healthcare, that have very strong unionization, have much better social services, but they do not have a job guarantee.

And you have people who may indeed have very generous unemployment benefits, but that’s not the same as having a job. And they find themselves being threatened by waves of refugees, who they fear are going to take their jobs. They have seen a decline in industrial manufacturing and they’re fearful for their jobs because there is not guaranteed employment. And so even in these nations, which have implemented, you might say a significant amount of social democracy, there is a significant part of the working class that is looking to authoritarian solutions and villainizing immigrants and refugees.

And I think for that reason, we need to take away Trump’s playbook of bringing jobs back to America, his promise of jobs by having a job guarantee. Tariffs, as we all know, will necessarily do one thing. They will increase the prices of imports, but they’re not going to lead manufacturers to invest in new production facilities if they’re wondering whether they’re really going to have a market let alone, whether they’re going to do so with any degree of significant employment. Absolutely. I think we have something else that we have to attend to.

Grumbine (00:49:29):

I agree wholeheartedly. And that brings me to the next point in your book here, which is fulfilling the right to an education. And I want to state for the record, I’ve spoken with the chairman of the board of directors, Raul Carrillo, of the Modern Money Network, and many others actually. And the one thing that jumped out, which I’m going to be honest, I didn’t know. And I felt kind of embarrassed that I didn’t know this, but I imagine I’m not alone in not knowing this.

There is no federal right to an education in this country. It was left as part of the state’s rights thing. This is a state issue. There is no federal right to an education. And so therefore states are sort of free to do what they want. And now the federal government has at times encumbered dollars as they’ve provided block grants or other things. And if you want this money, you’ve got to comply with XYZ. But the truth of the matter is, is that the states are under no obligation. So with that in mind, how would you guarantee a right to an education in a nation that still hasn’t settled 1865?

Winfield (00:50:35):

Yeah, well, not only the right to education is not in our constitution, but neither is the right to health care, the right to employment, the right to housing, or really the right to legal care in all cases, certainly in civil cases. So I think you have to recognize that we’re in a situation where there is this dilemma that really does require federal initiative.

And on the one hand, I think we need to have federal public funding of education because, you know, we all know that there are tremendous inequities in the amount of funding per student, between states and between localities within states. And much of that reflects the difference in property values and different communities. And the fact that state school funding depends in large part on real estate taxes, which are also completely unprogressive in the way they’re handled. They’re flat taxes.

So we need to overcome that with federal financing of public schools and indeed give more money to the students who are really struggling. And then when we’re talking about postsecondary education, we need to ensure that not only as Bernie would say, do we have free tuition at all public colleges, universities, and technical schools, but we have to give people a stipend to support them while they’re studying.

You know, they do this in Europe and you need it. You know, you can’t go to college if you have no means of paying your rent or buying food, et cetera. So that’s also part of the puzzle. We have to do that as well. And then we can begin to say that we have equal access to education. Otherwise we lack something that was regarded as crucial, interestingly enough, by the freed slaves at the end of the civil war, who demanded two things: one was 40 acres and a mule, but also free public education, which they of course had been deprived of.

Grumbine (00:52:19):

Both. Yeah. Let me jump to that for a second. It’s not in your book, but I don’t want to take a liberty here and ask. Reparations is something that, to the average person that is not modern monetary theory informed, it sounds kind of scary because it’s a lot of money and they have due a lot of money and they assume that that means they’re going to be taking from them. And so there’s a lot of resistance to making right, terrible wrongs.

I mean, 40 acres and a mule. If you do the math, I think Sandy Darity did the math and it is astronomical. And the amount of terrible peeling away of value from the labor of those afflicted individuals that were decimated by slavery within this nation. They have never, ever received anything but a kick in the teeth.

What is your stance on reparations and how do you see this playing into education? Because I’ve talked to a lot of people about the subject and none of them that I consider to be credible have ever said, it’s just a cash payment. In fact, Irami said he looks at reparations as earnest money on fixing a terrible wrong. In other words, there’s a lot more to do than just money. Money is just sort of putting cash down to say, yeah, we’re serious. What are your thoughts on reparations?

Winfield (00:53:36):

I mean, if you think about reparations as compensation, compensation for a wrong that a victim has suffered with the complicity of government, then we are talking about something that has equivalent value to that wrong. I think that’s different by the way, from the demand for 40 acres and a mule, which I think in the context of the South, where there was very little in the way of opportunities for free labor and also no commitment by government to have a job guarantee.

It was really a matter of fulfilling the right to livelihood, which is a separate issue from being compensated from past wrongs. And, you know, if you think about being compensated for past wrongs, you get something that in effect makes a sizable dent in a wealth gap, but it’s also something that comes to an end. Whereas when you enforce social rights, they never expire.

And for example, if you think about the income gap that is present between blacks and whites, it actually over the course of a working lifetime amounts to more than what the payment would be. If you were to calculate reparations based upon the value of 40 acres and a mule such as Darity does, you know, when it comes to maybe what I remember something, it could be seven or $800,000 for a family, but actually over the course of one’s working existence an African American will make seven to $800,000 less than a white, just as a woman will today make $418,000 less than a man over the course of the working career. Terrible.

So I think in a way the reparations would not suffice to eliminate either systemic racism or the gaps in wealth and income. And I think it also reflects really how it’s not wealth, but income, that is a key. And I think you see this in what I think is a mistaken path of those who, for example, want to say, we can achieve economic freedom and justice by having, for example, land reform, where everyone becomes a small little agricultural entrepreneur or micro-loans where everyone becomes a little entrepreneur or baby bonds where they’re equivalent, where everyone gets a certain stash when they become an adult.

You know, these sort of operate under this, I think illusory view that you can achieve economic independence as an entrepreneur. I think instead of guaranteed income, that is the real rock bottom of economic independence. And that is obviously something that amounts over the course of a lifetime to something of much greater significance than any particular stash one might be given.

You know, you think of what would happen if people had been given enough land and livestock to get by. Well today in America, 1.7% of breadwinners earn a living in agriculture. You know, the market is not going to let people remain solvent. We’re operating in small little entrepreneurs, agricultural farmers. It just doesn’t work that way. And there’s two sides to systemic racism. One is the gap in income and wealth that has resulted from official discrimination, legal discrimination of various sorts.

But then on the other hand, the other side of it is that those gaps are sustained and intensified by our allowing all the factors you need to exercise your autonomy as being things that require money, healthcare, access to education, housing, and so forth. All of these depend upon how much money you have. Well, when we fulfill the social rights agenda, we lift the boot of history off of everyone’s necks by ensuring that we all have access to healthcare, to education, to legal representation, to balancing work and family, to balancing the playing field between employer and employee and so forth independently of how much wealth we have. And that is something that transforms the situation in a permanent way.

Grumbine (00:57:45):

Yeah, that’s a huge deal. And you raised up a subject that was coming up here, which is the seventh chapter of your book. And I think clearly when you look at what is going on with the black lives matter protests, and you see what’s happening in this nation in general, we’ve had more and more opportunity to see the unequal treatment in the legal system and the ability to buy justice. Whereas most people don’t have access to representation, quality representation at that. You make that a key cog in your presentation here. And just to level set where we’re at in this, the last thing we’re going to do is we’re going to touch on fair funding of the social rights after this, but this legal right to representation is incredibly important. I want to hear your takeaway.

Winfield (00:58:33):

Yeah. I mean our whole legal system operates as a big toll booth that basically is preying on the poor and intensifying social disadvantage and with it both racial agenda disadvantage. And it does so with such things, obvious things, as cash bail, which is pretrial punishment for the poor, all the various fees that have proliferated, plea bargaining, which is the highway to mass incarceration.

But what also underlies all of these is that despite the bill of rights, which accords us our right to representation in criminal cases, we don’t have it for civil cases, which are no less important. And it’s enforced in criminal cases in a way that is fundamentally unequal because when you have to rely on court appointed lawyers or legal aid lawyers or pro bono, you’re dealing with much less legal resources than those who have money to hire their dream team.

You know, on average client of a legal aid lawyer sees them for one hour often, right before they go to court. They don’t have any resources for witnesses or do investigations. I mean, you have to have expert witnesses and the like.

So a way of winning this is different in a sense, apply the strategy of Medicare for all to legal care. We have a legal care for all system where we have a government funded legal insurance program where it fully covers the expenses of any personal criminal or civil legal representation. You go to any lawyer you want. You get your dream team and we can negotiate the fees on a national level to keep them affordable.

In this way, we all are going to have the ability to stand up for our rights in the workplace against sexual harassment, I think is key for the me too movement, against racial discrimination, against employment problems, problems with landlords, et cetera. One of the causes of homelessness is that most people, 85% who are in civil cases happen in representation. And you’re much more likely to be evicted in those cases than if you have a lawyer, so this is a key to really making us equal before the law. And unfortunately I haven’t heard of a single candidate other than myself offering the idea of legal care for all. But I think it’s a no brainer.

Grumbine (01:00:49):

It is absolutely. And it’s incredibly powerful. I’ve heard about it in philosophical circles and activist circles, but I have not heard someone actually take this as part of a platform. So this is in my opinion, very powerful. The last piece, and this is largely what our show typically discusses is basically funding the social rights movement funding, this whole concept. And as fellow MMTers, this is an area where we get a chance to really change the world.

I got to give a small anecdote here. Stephanie Kelton was recently on just yesterday, as a matter of fact, with Mark Blyth. And I had Mark Blyth on this show previously. He was an MMT skeptic. He was sympathetic. He was on the runway with us, but he was skeptic. Stephanie Kelton convinced him and flipped him and everything went great. So this is a good news story. So, so what are your thoughts on funding that.

Winfield (01:01:50):

I mean, first of all, when we are in a global depression, this is absolutely the worst time to follow any path of austerity or to follow the advice of these deficit hawks. You know when Lincoln had to save the union, when FDR had to let’s say, save democracy against fascism, they spent the money, they had the federal government fund what was necessary and they did not fall into hyperinflation. They were able to navigate a way out of that.

And we are in that situation as well, in a sense we’re in a better position than any other nation, to be able to make the public investments we need and not really worry about hyperinflation because we make investments that are productive, that ensure that ultimately people will get back to work, that there will be things to buy goods and services to buy that our money will be in a sense, something that actually operates. We can navigate this crisis.

Of course, we can also borrow money more easily than any other nation given how many other nations already hold vast amounts of our federal bonds and need to maintain the value of the dollar. But I think it’s good to tax. I think it’s good to tax those who have in a sense, this obscenely huge slice of our national wealth and income.

And I’m talking about the 1% in top 10%, the top 10% have more than close to 80% of our national wealth, which is the greatest amount of national wealth in human history. And the top 1% is almost doubled. Those are the bottom 90%. I think we should make the public investments, which we can do right now with the click of a button by the federal reserve into the accounts of the treasury.

But I think we should also move wealth that’s in the hands of the most privilege where it’s sitting in a manner that is largely unused and mobilize it to make the public investments we need. And I think we can have a very simple tax system. We don’t need any deductions and basically we can end all federal taxation of the bottom 90% and put the entire burden involving a highly graduated income and wealth tax on the top 10% in particularly the top 1% and everything can be easily funded with political support.

Grumbine (01:04:10):

Sure. And that’s the key is this all comes down the votes, right? But one question that I have for you, and this is a slight departure though, I’m seeing a convergence within the MMT community around this issue, and I’d love to hear your take on it. This is a hot take. Obviously we haven’t prepped for this, but the question is the George’s view of a land value tax. It definitely works to move money, to take unproductive rent seeking out of the equation and to penalize that kind of rent seeking behavior. And it moves things around. It kind of serves as that local mechanism to bring about equality. I’m just curious, what is your take on a land value tax?

Winfield (01:04:51):

I don’t think we need to focus on any particular kind of commodity as that which has to be taxed. I think rather we should focus on wealth and income in general. And I think also we don’t really need to focus on ceilings on either wealth or income. It’s more a matter of just ensuring that we make the public investments we need, and we have those who can most easily afford it and have so much wealth. They can’t be using it in a productive manner and then affect transfer that capital into economic engagements that really serve the public good and really serve economic growth in general. So I don’t think we need to focus on any particular kind of matter.

Grumbine (01:05:35):

I appreciate your take on that. Let me ask you. We’re through the book and obviously this pandemic, we’re going to our second wave here. It looks like a potential second shutdown. So it looks like the conditions that we’ve been living under, including those for your race are not going to get better anytime soon. In fact, we risk another shutdown. How do we reach it? How do we find your stuff within this pandemic? What are the things you working on and how might people find you?

Winfield (01:06:04):

Okay. I mean the first place to look as my campaign website, which is Winfield for senate.com all spelled out, W I N F I E L D for senate.com. I also have a new podcast called America Unchained, which we’ll be recording later today, it’s eighth episode. And I suggest people listen to it. I’m trying to discuss the issues at length seriously. And then of course, to look at the book Democracy Unchained, not to be confused with another title, which is called Democracy Unchained with another subtitle, which is a collection of essays,

Grumbine (01:06:41):

How to Rebuild Government for the People

Winfield (01:06:43):

Yeah, mine is a single author book. The subtitle is How We Should Fulfill Our Social Rights and Save Self-Government. And it’s available in a pretty inexpensive paperback, a pretty moderately priced hard back and in a very, very cheap Kindle edition. And you know, it’s topical, but it’s also meant to be a book for the ages. Cause I’m really trying to think about these rights in general. And I think the issue is that will apply not just in this election cycle, but forever.

Grumbine (01:07:12):

I agree with that. And I’ll tell you this podcast that we just did, we just walked through chapter by chapter of that book with a little editorial in there as well. And so I really appreciate you taking the time with us, Richard. This is the stuff that I think everyone needs to hear. And I look forward to hearing back from you in the future. Good luck in your campaign. And hopefully we’ll talk soon.

Winfield (01:07:36):

Yeah. Thank you. And I look forward to that opportunity because it’s hard to find opportunities that intelligent conversation at length about these issues. So thanks. Thanks for giving us that chance.

Grumbine (01:07:48):

You better believe it, man. I get it. All right. Well, look with that in mind. I want to thank everybody for tuning in. This is Steve Grumbine with Macro N Cheese and my guest Richard Winfield. We look forward to talking to you in the future. Have a great day. We’re out. [inaudible].

Ending (01:08:08):

Macro N Cheese is produced by Andy Kennedy, descriptive writing by Virginia Cotts and promotional artwork by Mindy Donham. Macro N Cheese is publicly funded by our Real Progressive Patreon account. If you would like to donate to Macro N Cheese, please visit patreon.com/realprogressives. [music]

Richard’s book: Democracy Unchained: How We Should Fulfill Our Social Rights and Save Self-Government

Richard’s website: WinfieldforSenate.com

Follow our guest(s) on Twitter: