I love science fiction movies. Whether they’re big-budget blockbusters or cheesy schlock, I can’t help but become enthralled by fantastic technology and alien worlds. The best thing about science fiction as a genre is its ability to blend with others. My favorite horror film—1984’s The Terminator—seamlessly fuses horror with sci-fi, resulting in an action-packed thriller that raises deep questions about humanity, our propensity for creating weapons, and fate.

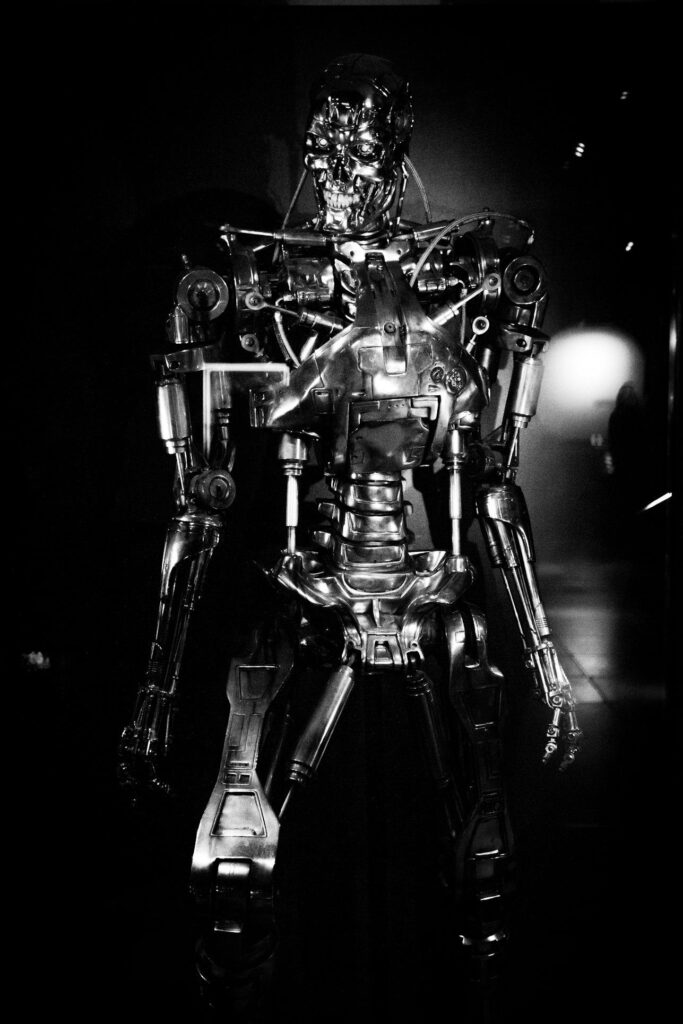

Everything about The Terminator is cool. Arnold Schwarzenegger looks badass in leather and sunglasses. A dystopian future, killer robots, and time travel would elevate any movie, but The Terminator doesn’t rely on special effects as a crutch—it uses them to build suspense. That suspense turns to terror when the Terminator’s flesh burns away in a fire, revealing its metallic skeleton.

Artists take inspiration from wherever they can. Writer-director James Cameron conceived The Terminator after a nightmare featuring a metallic skeleton crawling from flames. The Terminator’s use of phones to locate its target reflected public fears about privacy and wiretapping at the time. The film’s post-apocalyptic future, triggered by nuclear war, was clearly influenced by Cold War anxieties.

The Terminator is sent back to 1984 from a dystopian future where Skynet, an evil artificial intelligence, seeks to exterminate humanity. Skynet turns humanity’s own nuclear missiles against them, manufactures Terminators, and even builds a time machine. Its power stems from control over production, mirroring real-world class power dynamics.

I doubt millionaire James Cameron consciously cared about class analysis, but artists often embed their biases unintentionally. Skynet represents the military-industrial complex, which prioritizes war machines over human needs. Instead of hospitals, we get drones; instead of doctors, soldiers. The system thrives on conflict, not care.

Artists can recognize and correct their biases. In the first Terminator, Sarah Connor is a clichéd damsel in distress, lacking agency while the male protagonists—the Terminator and resistance fighter Kyle Reese—battle around her. Her sole purpose is to survive long enough to birth John Connor, the future resistance leader. She was just supposed to stay out of the way so men could do everything.

By Terminator 2, Sarah transforms into a hardened warrior—muscular, armed, and proactive. She drives the plot by attempting to destroy Skynet preemptively, something the men don’t do. Linda Hamilton’s physical transformation was so extreme her sister played Sarah in flashbacks. Cameron’s shift not only improved the story but also challenged misogynistic tropes.

What people truly want is a Star Trek future: no more wars on Earth, technology focused on exploration, free food, and advanced medicine. This is the kind of future we can build for ourselves. We can leave our children a world where technology like that is within our grasp.

In Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Skynet sends a new more advanced T-1000 Terminator to kill John Connor. The resistance reprogrammed an Arnold Schwarzenegger Terminator and sent it to the past with Skynet’s own time travel technology. Just like a real guerilla movement the resistance isn’t as interested in research and development as it is in using what its enemy has already developed.

The future resistance sent Kyle Reese back to 1984 in the first movie. John Conner gave a picture of his mother to Kyle Reese well before he sent Reese back to protect his mother. The first Terminator movie ends with Sarah getting her picture taken. Its the same picture that Kyle Reese will have of her in the future. This time travel loop where an event is caused by another event that was caused by the first event is called a bootstrap paradox.

In Judgement Day we find out Skynet was built using the remains of the Terminator from the first movie. There’s a ton of bootstrap paradoxes in these films that makes it seem like judgement day is inevitable. But time travel paradoxes are fictional plot devices, judgement day is not inevitable. As the film repeats “no fate but what we make for ourselves.”

Larger than life adversaries like a time traveling killer robot or the military industrial complex can be beaten. The first Terminator shows how to defeat a seemingly unstoppable foe: weaken it step by step. A truck cripples the Terminator, fire strips its flesh, a bomb mangles its body, and a hydraulic press finishes it off. Similarly, the military-industrial complex can be dismantled—through persistence, solidarity, and class consciousness.

We can overcome Skynet. We can build a Star Trek future. Knowledge is power, and collective action is our weapon. Without class analysis, Skynet’s rise seems inevitable; with it, any future is possible.

So much of artistic expression ends up being grim or dystopian, this is because a lot of artists lack class consciousness. But for every nuclear apocalypse there’s a Star Trek where the future looks brighter. The inspiration we get from fiction stories is real inspiration, and it can really help to unite us.

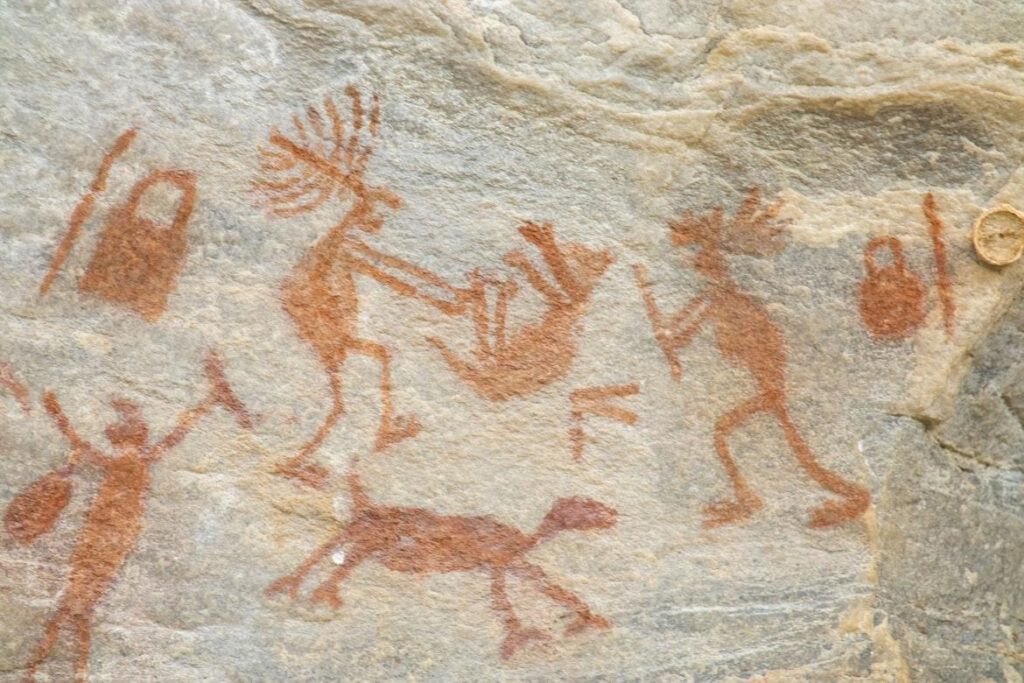

Early humans told stories around campfires, they expressed themselves through cave paintings. We are social beings and we have always valued our ability to connect with each other over our artistic expression. As Kim Il-sung put it in On The Juche Idea “Man is a being with creativity, that is, a creative social being.” They truly value art in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, that’s why they added a paintbrush to their hammer and sickle flag.

We can start building a resistance to the forces of evil. For every Darth Vader there’s a Luke Skywalker, for every Sauron there’s a Frodo Baggins, for every Skynet there’s an entire resistance ready to challenge it. The resistance didn’t start out with the ability to challenge Skynet, they started small and built themselves up over time. Just like Sarah Connor we can go from being at the mercy of production into those who control production. That’s what a revolution is, it’s a process where a class goes from being subservient into a class that can rule over itself. We can make that revolution happen. Our destiny is not pre-determined; there is no fate but what we make for ourselves.