This is part of a series, following on from the last installment that asked “Do We Need Taxes?”.

Originally posted on May 15, 2014 at the New Economic Perspectives blog.

Previously we have argued that “taxes drive money” in the sense that imposition of a tax that is payable in the national government’s own currency will create demand for that currency. Sovereign government does not really need revenue in its own currency in order to spend.

This sounds shocking because we are so accustomed to thinking that “taxes pay for government spending”. This is true for local governments, provinces, and states that do not issue the currency. It is also not too far from the truth for nations that adopt a foreign currency or peg their own to gold or foreign currencies. When a nation pegs, it really does need the gold or foreign currency to which it promises to convert its currency on demand. Taxing removes its currency from circulation making it harder for anyone to present it for redemption in gold or foreign currency. Hence, a prudent practice would be to constrain spending to tax revenue.

But in the case of a government that issues its own sovereign currency without a promise to convert at a fixed value to gold or foreign currency (that is, the government “floats” its currency), we need to think about the role of taxes in an entirely different way. Taxes are not needed to “pay for” government spending. Further, the logic is reversed: government must spend (or lend) the currency into the economy before taxpayers can pay taxes in the form of the currency. Spend first, tax later is the logical sequence.

Some who hear this for the first time jump to the question: “Well, why not just eliminate taxes altogether?” There are several reasons. First—as we said last time–it is the tax that “drives” the currency. If we eliminated the tax, people probably would not immediately abandon use of the currency, but the main driver for its use would be gone.

Further, the second reason to have taxes is to reduce aggregate demand. If we look at the United States today, the federal government spending is somewhat over 20% of GDP, while tax revenue is somewhat less—say 17%. The net injection coming from the federal government is thus about 3% of GDP. If we eliminated taxes (and held all else constant) the net injection might rise toward 20% of GDP. That is a huge increase of aggregate demand, and could cause inflation.

Ideally, it is best if tax revenue moves countercyclically—increasing in expansion and falling in recession. That helps to make the government’s net contribution to the economy countercyclical, which helps to stabilize aggregate demand.

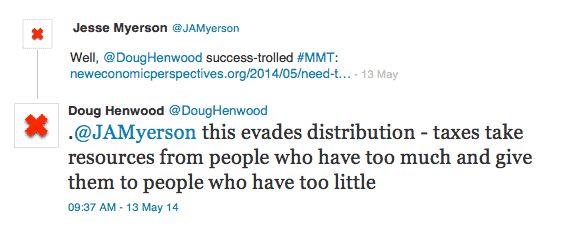

So, we covered those points last time, in part due to a silly twit by Doug Henwood, who likened this to “astrology”. Not one to be bothered with embarrassment he responded to the last blog with this exchange:

Well, no. Taxes on the rich might take “resources” from people who have too much—if he means that their demand deposit account is debited. But taxation does not “give them (the resources) to people who have too little”. Rather government spending directed to those who “have too little” is what gives the poor access to resources (they can use their demand deposit credits to buy food, clothing, shelter, and so on).

These are functionally two entirely separate activities. Government can spend to help the poor without taxing the rich or anyone else. And anyone who can understand balance sheets knows that there is no longer any balance sheet operation in which government “spends” its tax revenues.

Henwood seems to imagine that the rich roll their wheelbarrows full of coins up to the Treasury Department’s steps, where armored trucks load the cash up and take it out to make payments to the poor.

Doesn’t work that way. Tax payments debit the accounts of taxpayers. If you’ve ever gone to a ballgame you know that when the scorekeeper awards a run to Boston, he does not take it away from New York. Rather, he keystrokes runs to Boston. If after review of the video, the umpire has made an error, he “debits the account” of Boston. Where does the run taken away go?

That’s a question for the physicist, not the economist. Where do the taxes payments go? Nowhere—a bank account is debited. I think it has something to do with electrical charges changing from negative to positive, although some commentators told me it is all photons now. All I know is that taxes do not and cannot “pay for” spending.

All of this was recognized by Beardsley Ruml, a New Dealer who chaired the Federal Reserve Bank in the 1940s; he was also the “father” of income tax withholding and wrote two important papers on the role of taxes (“Taxes for Revenue are Obsolete” in 1946, and “Tax Policies for Prosperity” in 1964). Let’s first examine his cogent argument that sovereign government does not need taxes for revenue, and turn to his views on the role of taxes.

In his 1964 article, he emphasizes that “We must recognize that the objective of national fiscal policy is above all to maintain a sound currency and efficient financial institutions; but consistent with the basic purpose, fiscal policy should and can contribute a great deal toward obtaining a high level of productive employment and prosperity.” (1964 pp. 266-67) This view is similar to that propounded in by MMT.

He goes on to say that the US government gained the ability to pursue these goals after WWII due to two developments. The first was the creation of “a modern central bank” and the second was the sovereign issue of a currency that “is not convertible into gold or into some other commodity.” With those two conditions, “[i]t follows that our federal government has final freedom from the money market in meeting its financial requirements….National states no longer need taxes to get the wherewithal to meet their expenses.” (ibid pp. 267-8)

Why, then, does the national government need taxes? He counts four reasons:

(1) as an instrument of fiscal policy to help stabilize the purchasing power of the dollar; (2) to express public policy in the distribution of wealth and of income as in the case of the progressive income and estate taxes; (3) to express public policy in subsidizing or in penalizing various industries and economic groups; and (4) to isolate and assess directly the costs of certain national benefits, such as highways and social security. (ibid p. 268)

The first of these is related to the inflation issue we discussed above. The second purpose is to use taxes to change the distribution of income and wealth. For example, a progressive tax system would reduce income and wealth at the top, while imposing minimal taxes on the poor.

The third purpose is to discourage bad behavior: pollution of air and water, use of tobacco and alcohol, or to make imports more expensive through tariffs (essentially a tax to raise import costs and thereby encourage purchase of domestic output). These are often called “sin” taxes—whose purpose is to raise the cost of the “sins” of smoking, gambling, purchasing luxury goods, and so on.

The fourth is to allocate the costs of specific public programs to the beneficiaries. For example, it is common to tax gasoline so that those who use the nation’s highways will pay for their use (tolls on throughways are another way to do this).

Note that while many would see these taxes as a means to “pay for” government spending, Ruml vehemently denies that view in the title to his other piece, “Taxes for Revenue are Obsolete”. Government does not need the gasoline tax to “pay for” highways. That tax is designed to make those who will use highways think twice about their support for building them. Government does not need the revenue from a cigarette tax, but rather wants to raise the cost to those who will commit the “sin” of smoking.

Many would say that it is only fair that those who smoke will “pay for” the costs their smoking imposes on society (in terms of hospitalizations for lung cancer, for example). From Ruml’s perspective this is not far from the truth—the hope is that the high cost of tobacco will convince more people never to smoke, which thereby reduces the cost to society.

However, the point is not the revenue to be generated—government can always “find the money” to pay for hospital construction. Rather, it is to reduce the “waste” of real resources that must be devoted to caring for those who smoke. The ideal cigarette tax would be one that eliminated smoking—not one that maximized revenue to government. He said “The public purpose which is served [by the tax] should never be obscured in a tax program under the mask of raising revenue.” (1964 p. 268)

We can then use this notion of the public purpose to evaluate which taxes make sense. I won’t go through that today, but let me say that Ruml used the corporate income tax as an example of a particularly bad tax. He’s right. My professor Hyman Minsky always argued for abolishing that tax—and I wouldn’t be surprised if he got the idea from Ruml.

Of course, which tax do “liberals” love? Corporate income tax. They all want to increase it to “pay for” all the goodies they want to shower on the poor. In other words, they compound their confusion—not only do they insist on being wrong about the purpose of taxes, but they also embrace one of the worst ones! Maybe a good topic for another blog?

Ruml concluded both of his articles by arguing that once we understand what taxes are for, then we can go about ensuring that the overall tax revenue is at the right level. “Briefly the idea behind our tax policy should be this: that our taxes should be high enough to protect the stability of our currency, and no higher…. Now it follows from this principle that our tax rates can and should be lowered to the point where the federal budget will be balanced at what we would consider a satisfactory level of high employment.” (1964 p. 269)

This principle is also one adopted in MMT, but with one caveat. Ruml was addressing the situation in which the external sector balance could be ignored (which was not unreasonable in the early postwar period). In today’s world, in which some countries have very high current account surpluses and others have high current account deficits, the principle must be modified.

We would restate it as follows: tax rates should be set so that the government’s budgetary outcome (whether in deficit, balanced, or in surplus) is consistent with full employment. A country like the US (with a current account deficit at full employment) will probably have a budget deficit at full employment (equal to the sum of the current account deficit and the domestic private sector surplus). A country like Japan (with a currrent account surplus at full employment) will have a relatively smaller budget deficit at full employment (equal to the domestic private sector surplus less the current account surplus).

I’ll continue this thread.

39 RESPONSES TO “WHAT ARE TAXES FOR? THE MMT APPROACH”

- Charles Layne | May 15, 2014 at 7:16 pm |Quote:”Further, the second reason to have taxes is to reduce aggregate demand. If we look at the United States today, the federal government spending is somewhat over 20% of GDP, while tax revenue is somewhat less—say 17%. The net injection coming from the federal government is thus about 3% of GDP…”Isn’t that other 3% taken from the economy via sales of treasury notes, making government fiscal actions totally neutral , adding zero dollars to the economy?

- lrwray | May 16, 2014 at 5:47 am |charles: No. You are assuming that savers increase their saving BECAUSE govt sells bonds. In other words, if govt had not sold the bonds (ie left HPM in the economy) they WOULD NOT have saved. I find that highly implausible. This is a portfolio decision (stocks) not a saving decision (flows). Yes, on the margin there could be somebody who will save ONLY if there are treasuries to buy–but even that requires that NO ONE holding existing treasuries would give them up; otherwise it is still just a portfolio adjustment. And, anyway, the causation largely goes the other way: govt deficits result because someone wants to save.

- Robert Kelly | May 16, 2014 at 6:46 am |The sale of Treasury notes is for interest rate management. A 3% deficit creates an excess of reserves in the system, which drives the interest rate down. The Fed uses the interest rate as one of it’s tools to manage inflation. If it wants to target an interest rate above what it pays on idle reserves- .25-.50%-, it has to offer bonds at a rate reflecting that target.

Treasury notes do not take dollars out of the economy. The are like a savings account. Owners of those excess reserves can choose to let dollars sit idle, or buy a risk free, interest bearing bond. They could also spend them or invest them on something else. Banks, Pension funds and other institutional investors gladly buy up all the risk free, interest bearing Treasury securities that are offered. (And use them as collateral to borrow against in order to buy other financial instruments of higher risk.)

So the net injection of 3% never leaves the dollar denominated economy. Treasury notes are very liquid and can be redeemed or sold at anytime. This injection is all part of our “national debt”. It is dollars spent by our government that now is part of the savings of the non-government sector.

If everyone decided to cash in all of their Treasury notes at once and start to spend them, inflation would ensue. Then the government would have to increase taxes or offer a higher interest rate to get dollars out of the spending cycle. Taxes would erase/destroy the dollars and the higher interest rate bonds would provide incentive to put the dollars back into savings and out of circulation.

- Charles Layne | May 16, 2014 at 10:50 am |Thanks. I had to read it twice. 🙂 But it still seems to me that the sale of a Treasury takes dollars out of the economy for a period of time but I understand it is probably not circulating dollars but dollars that were static before the sale.

- Sean | May 16, 2014 at 11:58 am |Then the government would have to increase taxes or offer a higher interest rate to get dollars out of the spending cycle.As I understand it, interest rates are a much trickier issue than that, because they also represent income to savers. That is, offering a higher interest rate seems like it would be a stopgap measure with little long-term viability: even if those savers continually roll over their bonds (i.e., keep on saving because of the higher rates), eventually they’re gonna wanna spend it. And when they do, they may have accumulated quite the stash of savings.Or to look at this from a flows perspective, a higher interest rate will tend to increase the public deficit, which will increase the non-public (private plus external) surplus. Hence if the problem is too many privately-held financial assets, a higher interest rate may be harmful, or at best, not very helpful.

- Charles Layne | May 16, 2014 at 10:50 am |Thanks. I had to read it twice. 🙂 But it still seems to me that the sale of a Treasury takes dollars out of the economy for a period of time but I understand it is probably not circulating dollars but dollars that were static before the sale.

- MRW | May 16, 2014 at 2:30 pm |@Charles LayneIsn’t that other 3% taken from the economy via sales of treasury notes, making government fiscal actions totally neutral , adding zero dollars to the economy?Frank N Newman’s 87-page book (published April 2013) does a great job explaining how treasury bills/notes/bonds work, and what they are used for. It’s called Freedom From National Debt.

- Charles Layne | May 16, 2014 at 8:51 pm |Thanks. I saw that on Amazon. I’ll read it

- Charles Layne | May 16, 2014 at 8:51 pm |Thanks. I saw that on Amazon. I’ll read it

- lrwray | May 16, 2014 at 5:47 am |charles: No. You are assuming that savers increase their saving BECAUSE govt sells bonds. In other words, if govt had not sold the bonds (ie left HPM in the economy) they WOULD NOT have saved. I find that highly implausible. This is a portfolio decision (stocks) not a saving decision (flows). Yes, on the margin there could be somebody who will save ONLY if there are treasuries to buy–but even that requires that NO ONE holding existing treasuries would give them up; otherwise it is still just a portfolio adjustment. And, anyway, the causation largely goes the other way: govt deficits result because someone wants to save.

- GrkStav | May 15, 2014 at 10:17 pm |Thank you! While you do mention it clearly at the top, it’s probably useful to keep differentiating between taxes (and fees, etc) imposed by municipal, state and local, and ‘pegged-fixed-convertible-currency-using’ governments and our Federal or other sovereign, freely floating non-convertible currency issuers. This becomes particularly relevant when the discussion turns to ‘use taxes’ and ‘sin taxes’ many of which are imposed by city and state governments and are actually used to ‘fund’ those governments’ expenditures, either as ‘dedicated’ funds or as part of their General Fund.It is a bit sad to have to think of it this way, but we all have to think of how any particular sentence or two of our writing in such settings may be quoted in social media to present a false impression.

- John Hobgood | May 15, 2014 at 10:36 pm |Puts the function of currency in the proper perspective and is very understandable. Looking forward to the next installment.

- John Hobgood | May 15, 2014 at 10:44 pm |Charles –Those dollars that were seeking Treasury notes were not banging on the shopkeeper’s door in the first place.

- JP | May 15, 2014 at 10:59 pm |Charles, treasury notes drain reserves. They don’t drain aggregate spending. Banks are the biggest buyers of t-notes.

- Charles Layne | May 16, 2014 at 10:29 am |JP and Steve:Thanks, I understand but please explain why we have the “bean counter rule” that govt spending minus taxes must equal notes bought/sold by the Treasury? What is the functional need of the process?

- MRW | May 16, 2014 at 6:37 pm |@CharlesBasically, the government, the US Treasury, spends first to provision itself on whatever Congress has authorized. This adds new money issued by the Treasury into the economy. THEN, the US Treasury issues treasury securities in the same amount to be sold at auction to the American public, and the foreign sector, which brings the money supply back to balance.The Central Bank cannot buy those securities by law (it can only buy them on the open market, by law). It does not control their issue, it does not have those dollars to “loan” to the government, and it does not create dollars to loan to the government.Here is Frank N. Newman, former Deputy Treasurer of the US Treasury explaining it:When the Treasury distributes funds, the nation’s deposits are initially increased. Where can the bank money go? Let’s look at an example, excluding the portion covered by taxes. Typically, before the Treasury issues $20 billion of securities, the government has distributed $20 billion to the public from its account at the Fed: redeeming maturing Treasuries, paying companies that provide goods and services for the government, for payments to individuals, etc. Many investors simply “roll over” their Treasury securities, replacing maturing ones with newly issued ones, and taking just the interest. For example, perhaps $10 billion of the $20 billion issue might be in that category. The Treasury pays out the other $10 billion to the private sector. At that point, a set of participants in the U.S. financial system will have the extra $10 billion in their bank accounts and will look to place those funds.The money supply has been increased by $10 billion, and the new dollars move around within the overall US financial system. All the Treasuries previously available are already owned by investors, and prior auctions had demand that exceeded the amount offered.[paragraph break inserted for reading ease]

As the new Treasuries are auctioned, the demand is filled by exactly the $10 billion offered, and the money supply returns to its prior level. In the whole of the U.S. financial system, the only place to put the money is into the new Treasuries that are being auctioned— or otherwise just leave the funds in banks. If some investors choose to buy other financial assets with those new funds, such as corporate bonds or stocks, then someone else— the sellers of those assets— will end up with the bank deposits, and will be looking for a place to invest them. There are no other USD financial assets to invest in that are not already owned by someone. And the dollars cannot go to another country [MRW: again, this is by law]; an individual investor can choose to invest some dollars in assets in another country, but then the foreigners who sold those assets would just own the same dollars in U.S. banks. The aggregate of all investors have, in the end, two choices: leaving the extra $ 10 billion of cash in bank deposits, which earn very little, if any, interest, and are not guaranteed by the government beyond $250,000; or exchanging some of their bank money for the new Treasuries, which pay interest and have the “full faith and credit” of the United States.Newman, Frank N. (2013-04-22). Freedom from National Debt (Kindle Locations 255-271). Two Harbors Press. Kindle Edition.More: Frank Newman wrote this on Page 18 of his Freedom from National Debt.In the process of Treasury issuance and redemption, the money involved changes hands but cannot leave the U.S. financial system. There is a huge, deep market for Treasuries, with an average of over $500 billion per day traded. Typically when the Treasury issues securities, it has already distributed funds to the bank accounts of investors redeeming securities and to recipients of government payments, from the Treasury account at the Fed. Treasury has been generally keeping about $100 billion, sometimes up to $300 billion, on deposit at the Fed— that is in addition to the hundreds of billions of other assets, including gold and silver, held by the Treasury. Sometimes the Treasury issues securities temporarily in advance of disbursement, mostly as part of planning for seasonal variations. Generally, the Treasury uses bank money newly received from tax collection and Treasury issuance to replenish its deposit accounts at the Fed.Our Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, does not loan to the government.

- Charles Layne | May 17, 2014 at 8:59 am |Thanks for the tip re Newman’s book. I read almost half of it last night before succumbing to sleep. I was somewhat surprised because he says, unequivocally, the same thing I have said here. The Federal Govt, as currently operating, cannot change the quantity of money in the economy. That power is vested exclusively in commercial banks and to a small degree, to the Fed. The only thing Federal spending can do is what John Hobgood implies in his remark; Federal spending can move money around in the economy from static locations to more active uses but the quantity remains the same. So John Kenneth Galbraith was very correct when he stated in his book on “M0ney…” that “banks cause inflation” and the flip side has to be true as well, banks cause deflation too. So Alt’s diagram of the Federal govt spigot pouring money into the economy should be replaced, to reflect reality, with a whisk, stirring up the money. And his money introduction spigot into the economy should come from commercial banks to be consistent with reality. Then he needs to show the capability of banks to remove money from the economy, perhaps as a sump pump, because that too is as powerful as the tax drain, perhaps more powerful because it is more stealthy. That said, I return to an earlier remark that I made, the interaction of commercial banks with the economy seems to be ignored here in the annals of MMT when it should be a key area when considering the money supply in the economy.

- Gus | May 17, 2014 at 4:33 pm |MRW or anyone else: Can you explain this part of the Newman quote?” The aggregate of all investors have, in the end, two choices: leaving the extra $ 10 billion of cash in bank deposits, which earn very little, if any, interest, and are not guaranteed by the government beyond $250,000; or exchanging some of their bank money for the new Treasuries, which pay interest and have the “full faith and credit” of the United States.”It seemed like all this time he was referring to the central bank reserves, where they can’t escape from on aggregate. But the $250,000 remark now sounds like it’s referring to FDIC insurance which I thought would only apply to commercial banks. Wouldn’t the fed be considered to be inherently backed up by the full faith & credit of the US, and in no way open to a bank run or failure? Or was he really talking about commercial bank deposit money, which can’t escape the system and are used to buy treasuries at auctions?

- steve@ssgreenberg.name | May 17, 2014 at 9:08 pm |Gus,>not guaranteed by the government beyond $250,000

Refers to commercial bank deposits.The Fed is backed up by its ability to create money at will.Treasuries are backed up by the full faith and credit of the government.Commercial bank reserves are on reserve at the Fed. If they want more interest, Commercial Banks buy treasuries with their reserves at the Fed.Actually the treasury does not issue new money, the Fed does that. For reasons that make little sense anymore (if they ever did), it is complicated how Treasuries end up with money from the Fed. The complicated transactions don’t modify the impact very much. (At least that is how I remember it from readings on this web site.)

- Charles Layne | May 18, 2014 at 1:26 pm |Originally, when the Fed was instituted, the Treasury printed a uniform series of bills or notes that were used by all banks to signify how much gold was owed to the bearer of the bill. The bills were not money; they were just a paper note. That changed in 1933 when FDR did away with gold “backing” for those notes. But that phrase, “removed the backing”, is deceptive because what he really did was convert those bills into money, fiat money. The conversion was then completed by Nixon when he removed the backing for international exchanges, backing out of the Breton Woods agreement, thereby giving us an international fiat currency. The problem then became that the US Treasury was put in the position of creating legal money and giving it to banks. And now all the bank supporters try to construct stories to justify this process that essentially started because of the scarcity of gold.

- steve@ssgreenberg.name | May 18, 2014 at 2:09 pm |Charles,You said “this process that essentially started because of the scarcity of gold.”That may have been in the minds of the people who made these changes. However, MMT is saying that backing money by gold is an unnecessary idea, and is actual very harmful to the development of a growing economy with rapidly improving technology and living standards.Perhaps Roosevelt and Nixon were forced by circumstances to stumble on the correct policy. Now its time to fully recognize how things have changed and act like we have a fiat currency, because a fiat currency is exactly what we have. It does harm to pretend that we have some other kind of currency when we don’t have that other kind of currency.

- steve@ssgreenberg.name | May 18, 2014 at 2:09 pm |Charles,You said “this process that essentially started because of the scarcity of gold.”That may have been in the minds of the people who made these changes. However, MMT is saying that backing money by gold is an unnecessary idea, and is actual very harmful to the development of a growing economy with rapidly improving technology and living standards.Perhaps Roosevelt and Nixon were forced by circumstances to stumble on the correct policy. Now its time to fully recognize how things have changed and act like we have a fiat currency, because a fiat currency is exactly what we have. It does harm to pretend that we have some other kind of currency when we don’t have that other kind of currency.

- Charles Layne | May 18, 2014 at 1:26 pm |Originally, when the Fed was instituted, the Treasury printed a uniform series of bills or notes that were used by all banks to signify how much gold was owed to the bearer of the bill. The bills were not money; they were just a paper note. That changed in 1933 when FDR did away with gold “backing” for those notes. But that phrase, “removed the backing”, is deceptive because what he really did was convert those bills into money, fiat money. The conversion was then completed by Nixon when he removed the backing for international exchanges, backing out of the Breton Woods agreement, thereby giving us an international fiat currency. The problem then became that the US Treasury was put in the position of creating legal money and giving it to banks. And now all the bank supporters try to construct stories to justify this process that essentially started because of the scarcity of gold.

- steve@ssgreenberg.name | May 17, 2014 at 9:08 pm |Gus,>not guaranteed by the government beyond $250,000

- Charles Layne | May 17, 2014 at 8:59 am |Thanks for the tip re Newman’s book. I read almost half of it last night before succumbing to sleep. I was somewhat surprised because he says, unequivocally, the same thing I have said here. The Federal Govt, as currently operating, cannot change the quantity of money in the economy. That power is vested exclusively in commercial banks and to a small degree, to the Fed. The only thing Federal spending can do is what John Hobgood implies in his remark; Federal spending can move money around in the economy from static locations to more active uses but the quantity remains the same. So John Kenneth Galbraith was very correct when he stated in his book on “M0ney…” that “banks cause inflation” and the flip side has to be true as well, banks cause deflation too. So Alt’s diagram of the Federal govt spigot pouring money into the economy should be replaced, to reflect reality, with a whisk, stirring up the money. And his money introduction spigot into the economy should come from commercial banks to be consistent with reality. Then he needs to show the capability of banks to remove money from the economy, perhaps as a sump pump, because that too is as powerful as the tax drain, perhaps more powerful because it is more stealthy. That said, I return to an earlier remark that I made, the interaction of commercial banks with the economy seems to be ignored here in the annals of MMT when it should be a key area when considering the money supply in the economy.

- MRW | May 16, 2014 at 6:37 pm |@CharlesBasically, the government, the US Treasury, spends first to provision itself on whatever Congress has authorized. This adds new money issued by the Treasury into the economy. THEN, the US Treasury issues treasury securities in the same amount to be sold at auction to the American public, and the foreign sector, which brings the money supply back to balance.The Central Bank cannot buy those securities by law (it can only buy them on the open market, by law). It does not control their issue, it does not have those dollars to “loan” to the government, and it does not create dollars to loan to the government.Here is Frank N. Newman, former Deputy Treasurer of the US Treasury explaining it:When the Treasury distributes funds, the nation’s deposits are initially increased. Where can the bank money go? Let’s look at an example, excluding the portion covered by taxes. Typically, before the Treasury issues $20 billion of securities, the government has distributed $20 billion to the public from its account at the Fed: redeeming maturing Treasuries, paying companies that provide goods and services for the government, for payments to individuals, etc. Many investors simply “roll over” their Treasury securities, replacing maturing ones with newly issued ones, and taking just the interest. For example, perhaps $10 billion of the $20 billion issue might be in that category. The Treasury pays out the other $10 billion to the private sector. At that point, a set of participants in the U.S. financial system will have the extra $10 billion in their bank accounts and will look to place those funds.The money supply has been increased by $10 billion, and the new dollars move around within the overall US financial system. All the Treasuries previously available are already owned by investors, and prior auctions had demand that exceeded the amount offered.[paragraph break inserted for reading ease]

- Charles Layne | May 16, 2014 at 10:29 am |JP and Steve:Thanks, I understand but please explain why we have the “bean counter rule” that govt spending minus taxes must equal notes bought/sold by the Treasury? What is the functional need of the process?

- Larry Kazdan | May 16, 2014 at 1:54 am |“Of course, which tax do “liberals” love? Corporate income tax. They all want to increase it to “pay for” all the goodies they want to shower on the poor. In other words, they compound their confusion—not only do they insist on being wrong about the purpose of taxes, but they also embrace one of the worst ones! Maybe a good topic for another blog?”Yes, hope you will publish this clarifying blog. Since consumers/workers are indebted whereas corporations are sitting on piles of cash, it is not clear to me why all taxes should fall on the former and none on the latter.

- MRW | May 16, 2014 at 2:35 pm |(1) They fall on the latter when it’s the state or province doing the taxing because state and local govts need revenue. (2) Corporations get their customers to pay their taxes via prices.

- MRW | May 16, 2014 at 2:35 pm |(1) They fall on the latter when it’s the state or province doing the taxing because state and local govts need revenue. (2) Corporations get their customers to pay their taxes via prices.

- SteveD | May 16, 2014 at 2:41 am |@ Charles Layne:

Deficit spending always results in the creation of a net financial asset. Unlike private loan issuance, which incorporates both a private sector liability and asset, government deficit spending results in no corresponding private sector liability and ONLY a private sector asset (The government bond). - Andy | May 16, 2014 at 3:09 am |Professor Wray.

It seems to me that it may be feasible and for additional currencies at the local level (US: State UK: County) to be introduced by the local authorities. After all they collect local taxes, fines, business and household rates etc and also purchase local goods and services along with Labor. With the cooperation of the local community do you think this might be a way of stimulating the economy from the bottom up ? - Tyler | May 16, 2014 at 7:29 am |I tweeted to Henwood last night that it is an indisputable fact that the US government does not spend revenue. He didn’t reply, which I think is a good sign.

- Dan Sullivan | May 16, 2014 at 10:41 am |Before money, each citizen (or tribe member) was expected to personally contribute to the good of the community in some way, by grading roads, serving in the militia, feeding those who graded roads and served, and so on.Issuing money by hiring people to do those things simply gives them credit for having done them. Those who accept the money have indirectly aided the process. That is, those who feed or clothe the road graders are now paid from what the road graders had been paid. Then those who build shelters for these farmers and tailors are supporting the road grading even less directly. The real contribution of wealth and service comes when one accepts the money, not when one renders it back to government.Randall Wray is absolutely right that issue precedes collection, not only because one cannot collect what has not been issued, but because the money is itself a certificate of contribution to the community, and the purchasing power of money originates with that certification.This begs the question of what contributions banks have made that they can issue credits that are given the same standing as money.

- Charles Layne | May 16, 2014 at 8:45 pm |Amen, Dan, to the remark re contributions by banks. I see all too little in the MMT studies regarding the interaction of banks with the economy.

- Dan Sullivan | May 17, 2014 at 8:39 am |Mosler has been relatively silent on this, but his devotees are hostile to the idea that the creation of money by banks is a usurpation of the principle of money as a credit for government service already rendered. They become almost hysterical and say that taking away the money issuing privilege “would end banking as we know it,” without acknowledging that banking as we know it had been destructive long before deregulation.

- Charles Layne | May 17, 2014 at 3:41 pm |Dan, all I can say is “Amen” again. Ending “banking as we know it” is a very noble goal. I hope to post more on the subject in the near future.

- Charles Layne | May 17, 2014 at 3:41 pm |Dan, all I can say is “Amen” again. Ending “banking as we know it” is a very noble goal. I hope to post more on the subject in the near future.

- Dan Sullivan | May 17, 2014 at 8:39 am |Mosler has been relatively silent on this, but his devotees are hostile to the idea that the creation of money by banks is a usurpation of the principle of money as a credit for government service already rendered. They become almost hysterical and say that taking away the money issuing privilege “would end banking as we know it,” without acknowledging that banking as we know it had been destructive long before deregulation.

- Andy | May 18, 2014 at 1:46 pm |“This begs the question of what contributions banks have made that they can issue credits that are given the same standing as money.”Facilitating investment ?

- Charles Layne | May 16, 2014 at 8:45 pm |Amen, Dan, to the remark re contributions by banks. I see all too little in the MMT studies regarding the interaction of banks with the economy.

- entreposto | May 16, 2014 at 10:44 am |I’d second the request for more discussion on eliminating the corporate tax. The old “double taxation” argument was NEVER satisfying and always sounds like an aggravating whine of greedy self-interest.

- vladimir gagic | May 16, 2014 at 10:58 am |The way I understand MMT is that it’s similar to an electrical circuit: taxes are the ground, Treasury the generator, and money is current. Without a ground, electricity wouldn’t flow, and without taxes, money wouldn’t do anything.

- Guglielmo Tell | May 16, 2014 at 11:07 am |A would-be modern Marxist approach: an economy that functions with total honesty doesn’t need taxes.

- MRW | May 16, 2014 at 2:08 pm |Dr. Wray, you around? I have a small quibble.And anyone who can understand balance sheets knows that there is no longer any balance sheet operation in which government “spends” its tax revenues.What do you mean by no longer any balance sheet? What are you referring to? — Thx

- Sam McCallister | May 16, 2014 at 2:40 pm |Beardsley Rum and his number (3): “to express public policy in subsidizing or in penalizing various industries and economic groups” An excellent, morally upstanding view of why corporations should be taxed rather than paying no taxes at all. Conservatives have always claimed the moral high ground, so this should appeal to them. Agreed, taxation has nothing to do with “paying for” Government spending. It has long been a right wing argument, or a deceitful appeal to so-called morality, or what they will insist is morally upstanding – that has been entrenched policy. In other words, Government can help the poor but they have refused to do so. Similarly, taxation or penalization seems appropriate for corporations whose very operations depend on a continual subsidy from the Federal Government. We don’t bother to question what “work” many of these corporations are actually doing, we just assume jet fighters, or justice system databases are “work”. (Can the author name some corporations that don’t depend on explicit subsidies from various levels of Government, aside from enjoy limited taxation?) Taking this further, we can convincingly call for a sin tax on investors? Wealth, which brings access, and information, enjoys a tremendous advantage over a consumer who, for example, is being set up to fail in a major consumer purchase, especially if this purchase is an essential human need that has been inflated beyond affordability.

Yet, even with millions of examples of that in our country, we refuse to see a problem with investing.

Also, Corporations weren’t orgininally intended to get people rich and pad shareholders coffers, they were purposed to benefit society as a whole. If investors successfully destroy entire neighborhoods, ship off entire industries to locations that favor slave labor, blame imaginary welfare recipients for decades (whose so-called largress should be even more trivial now that we understand a sovereign Government), then suddenly wave a magic wand to state the obvious about how poor people could have been helped all along through a so-called new understanding of money – doesn’t restore credibility to the same relatively brutal arguments about so-called growth and production, conditions that are no longer be possible or sustainable. Taxation, then, as it was originally intended, is for the benefit of the nations citizens. - Gus | May 16, 2014 at 7:08 pm |“We would restate it as follows: tax rates should be set so that the government’s budgetary outcome (whether in deficit, balanced, or in surplus) is consistent with full employment. A country like the US (with a current account deficit at full employment) will probably have a budget deficit at full employment (equal to the sum of the current account deficit and the domestic private sector surplus).”What was meant by the second sentence here? Isn’t that just a sectoral balance identity? I thought you’ve shown that the government deficit determines the private surplus, not the other way around, given a relatively static current account deficit. So couldn’t you (unsustainably) have full employment with a budget surplus and large private deficit (late 90’s)? It seems like you could even force full employment with a job guarantee and still have your choice of tax rates to run a balanced government budget or surplus, though maybe that falls apart somehow.I understand what point you were making (distinguishing between countries’ target deficit size based on trade balances), but it seems like you left out the part about making a policy choice about the target private sector flow. For instance a country could possibly target no flow for the private sector, by way of government deficit aimed at exactly the trade deficit. I’ve only heard Warren Mosler dismiss this by saying “we want private sector surplus because the private sector wants to save, and we’ve built in incentives for the private sector to save”.

- Pingback: Randy Wray: What are Taxes For? The MMT Approach | naked capitalism

- Steven Greenberg | May 17, 2014 at 8:36 am |MRW,You originally quoted “there is no longer any balance sheet operation”. Operation is a very important word in this phrase. Wray did not say “there is no longer any balance sheet”When a bank lends money, there is also the operation of putting a debit on the balance sheet of the borrower. When the government creates money, there is no corresponding balance sheet operation of creating a debit somewhere.

- Geoff Coventry | May 17, 2014 at 3:03 pm |Randy,

Have you posted elsewhere on ideal tax structures? I’d like to read more about the pros & cons of taxes on different sectors/activities.

Thx! - steve@ssgreenberg.name | May 17, 2014 at 9:14 pm |Somewhere around the Nixon administration, the Federal Government started giving huge block grants to the states. I don’t know the current state of these block grants, whether they still exist at all, or if they do, how they have changed in size.Conceptually, I suppose, the Federal Government could give large enough block grants to the States and localities so that they wouldn’t have to charge taxes either to fund their operations. I wonder what MMT experts would say about that possibility.Of course such huge block grants are fraught with political and practical problems, but perhaps those could be worked out.

- Vernon Huffman | May 17, 2014 at 11:36 pm |It seems to me that if government hopes to stabilize the dollar, they should end the practice of Fractional Reserve Lending. As long as banks can create money as debt, we’ll all be working to pay off interest. The current distribution of wealth is all upward.