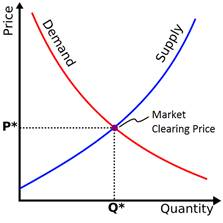

Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics, published in 1890, stands as a seminal work that has profoundly shaped the trajectory of what has become to be defined as “basic economics”. It solidified the mainstream concepts of supply and demand, offering a subjective, yet tractable model for explaining how prices and quantities are determined. This model, which posits that market equilibrium is achieved through the interplay of consumer utility and producer costs, became the cornerstone of mainstream (neoclassical) economics.

Its pervasive influence, however, is problematic, as its simplistic epistemology and ontology leads to flawed conclusions regarding the intricacies of the real world. Marshall’s framework, while elegant in its simplicity, commits a fallacy of misplaced concreteness. The model, presented as a universal truth, constitutes psychological reductionism, reducing complex human motivations and social structures to a narrow set of pseudo-mathematical calculations. The idealistic ceteris paribus assumption isolates variables in a manner that (purposefully) negates the real world.

The Demand Curve

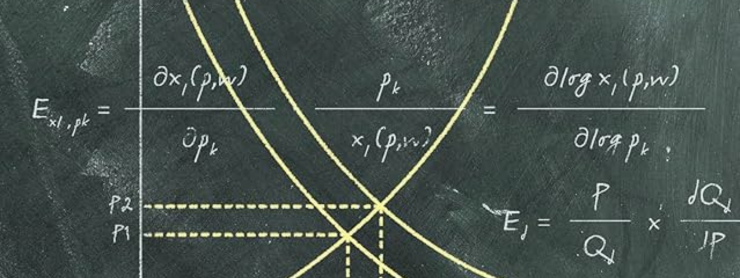

The Marshallian demand curve is derived from utilitarian theory, which posits the pursuit of consumer happiness through commodity consumption within a binding budget constraint. It illustrates the quantity of a good a consumer will demand at various price levels, assuming all other factors (income, prices of other goods, preferences) remain constant. While appealingly demonstrating a straightforward inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded, its analytical use is hampered by its inherent conflation of two distinct effects of a price change, that is, the substitution effect and the income effect.

When the price of a good changes, consumers are theorized to respond in two primary ways. The substitution effectcaptures the consumer’s tendency to shift consumption away from the now relatively more expensive goods towards relatively cheaper alternatives, while maintaining the same level of satisfaction. This effect highlights the responsiveness of consumer choices to changes in relative prices. The income effect arises because a change in price alters the consumer’s real income or purchasing power. If the price of a good falls, the consumer’s real income effectively increases, allowing them to purchase more of all goods. Conversely, a price increase reduces real income, potentially leading to a decrease in consumption.

The problem, hence, lies in the inability to disentangle these two effects. It presents a combined effect of price changes on quantity demanded, yet without effectively comprehending the contribution of each individual effect. This conflation renders the Marshallian demand curve less precise for a comprehensive understanding of the actual behavioral responses to price changes. It cannot precisely indicate how much of a change in quantity demanded is attributable solely to a change in relative prices versus a change in purchasing power. This lack of precision complicates accurate consumer welfare measurement.

For instance, an increase in the price of a good could lead to an increase in the quantity demanded. This paradox occurs primarily for low-income households. When the price of a staple good, like bread or rice, rises, consumers, facing severe budget constraints, may find themselves unable to afford more expensive substitutes (such as meat or vegetables). Consequently, they are compelled to purchase more of the now relatively more expensive staples to meet their basic needs. There is also a scenario when demand increases with price due to the perceived symbolic representation of a commodity, that is, the invocation of a particular social status that manifests itself via luxury appeal. The complexities of consumer behavior reflect particularities that the assumed demand curve cannot adequately disentangle. What exactly then is an effective definition of rationality?

Moreover, the acute vulnerability of the Marshallian demand curve lies in its struggle to unequivocally establish and theoretically justify a downward slope. While the bedrock assumption is an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded, the Marshallian framework, in its aggregative form, finds it remarkably difficult to provide a robust and unimpeachable underpinning for this seemingly universal phenomenon. This conceptual ambiguity is not merely a theoretical nuance; it carries significant implications for the model’s practical use. The inability to definitively confirm a downward slope within its own constructs severely curtails the model’s predictive power of consumer choice. If the direction of the relationship between price and quantity cannot be established, forecasts based on the model regarding consumer responses to price changes are therefore unreliable.

The Supply Curve

At the heart of the Marshallian supply curve is the idea that while we examine the relationship between price and quantity for one good, all other factors remain constant. This simplification proves increasingly problematic as we consider significant shifts in production volumes. The “all else being equal” condition unravels. An increase in the production of one commodity can ripple through the entire economic system. If this increased production demands a greater quantity of a specific raw material, the fundamental dynamics of that material’s market—its price and availability—will be concretely altered. This change, in turn, directly affects the production costs of other industries that also rely on the same raw material. Such interdependencies highlight a generality, that is, supply is not merely a collection of atomistic production silos. Instead, it is a complex web of shared resources, elaborate supply chains, and the pervasive influence of technological spillovers, all dictated by the level of effective demand.

Firms are not price-takers. The notion of perfectly competitive markets where individual firms have no influence over prices is an idealized social construction. Industries, particularly those dominated by a few large players, exhibit characteristics of oligopoly and monopoly. Firms are capable of influencing prices through their production decisions, pricing strategies, and organizational maneuvers. This deviation from the price-taking assumption is crucial because it implies that the supply curve as understood as upward sloping does not accurately represent the firm’s output.

Collusion and coercion reign supreme. Collusion, whether explicit or tacit, allows firms to collectively restrict output and manipulate prices, effectively creating an artificial scarcity that drives up prices beyond what would prevail in a truly competitive market. Coercion can manifest in various forms, from predatory pricing designed to drive out competitors to the exploitation of market dominance to impose unfavorable terms on suppliers, workers, or consumers. These practices disrupt the vogue perception of the relationship between cost and supply. Significant economies of scale result in decreasing production costs, which contradicts the assumption of naturally diminishing returns. The existence of market power challenges the universal applicability of the upward-sloping supply curve.

The Takeway

The assertion that prices are solely determined by the interplay of supply and demand, often referred to as “market forces,” is ad hoc. There is a problem of circularity: if consumer and producer behavior is contingent upon price fluctuations, and price fluctuations are, in turn, dependent on producer and consumer behavior, how does the model effectively capture a market-clearing price? Consumer choices extend far beyond simple utility maximization based on price and income. It is essential to assess broader sociological factors such as prevailing cultural paradigms, social class divisions, deeply ingrained ethical considerations, and even fleeting fashionable trends, all of which profoundly dictate how much consumers are willing to pay for goods and services. Similarly, producer decisions regarding pricing and output are not solely driven by an idealized competitive cost structure; producer behavior is influenced by standardized techniques of production, sophisticated marketing strategies, and ingrained organizational behavior that are heavily shaped by prevailing industry norms.

The profound significance of power dynamics is an undeniable truth, particularly when observing the behavior of monopolies and oligopolies. These concentrated market structures wield immense influence, leveraging their dominant positions to dictate terms and extract disproportionate benefits. By controlling a substantial share of a particular market, these entities establish prices that far exceed production costs. This extraction of wealth is not a benign process; it is a direct consequence of the exploitation inherent in their dominant market positions.

One prominent example is the imposition of unfavorable contract terms on suppliers. Faced with a limited number of buyers for their goods or services, suppliers often have little recourse but to accept terms that significantly erode their profit margins, limit their ability to innovate, or even threaten their very existence. This imbalance of power can stifle competition further down the supply chain, as smaller suppliers struggle to compete against those with more favorable terms from dominant buyers.

By virtue of monopsony, which is emblematic of market dominance, firms suppress wages. With fewer employers vying for labor extraction, workers have less bargaining power and fewer alternative employment options, which leads to stagnant wages, reduced benefits, and a decline in overall living standards. Moreover, beyond direct wage suppression, firms unilaterally dictate working conditions, limit opportunities for upward labor mobility, and impede labor unions as an effective countervailing force for social justice.

The fixation on supply and demand curves as the primary, if not sole, determinant of allocation engenders profound misunderstandings. It simplifies the tapestry of human needs and aspirations into a narrow calculus of consumer satisfaction. It mystifies production, which is a collaborative endeavor shaped by institutional arrangements. By disregarding relational aspects, the ideology of “basic economics” is limited in scope, which makes it exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to genuinely address persistent patterns of socioeconomic inequity, endemic to an economy whose modus operandi rests on accumulation of wealth at one pole and misery on the other. It constitutes a sanitized depiction of reality.