Originally published December 18, 2011 on the New Economic Perspectives blog.

In the Primer we discussed the general case of government spending, taxing, and bond sales. To briefly summarize, we saw that when a government spends, there is a simultaneous credit to someone’s bank deposit and to the bank’s reserve deposit at the central bank; taxes are simply the reverse of that operation: a debit to a bank account and to bank reserves. Bond sales are accomplished by debiting a bank’s reserves. For the purposes of the simplest explication, it is convenient to consolidate the treasury and central bank accounts into a “government account”.

To be sure, the real world is more complicated: there is a central bank and a treasury, and there are specific operational procedures adopted. In addition there are constraints imposed on those operations. Two common and important constraints are a) the treasury keeps a deposit account at the central bank, and must draw upon that in order to spend, and b) the central bank is prohibited from buying bonds directly from the treasury and from lending to the treasury (which would directly increase the treasury’s deposit at the central bank). The US is an example of a country that has both of these constraints. In this blog we will go through the complex operating procedures used by the Fed and US Treasury. Scott Fullwiler is perhaps the most knowledgeable economist on these matters, and this discussion draws very heavily on his paper. Readers who want even more detail should go to his paper, which uses a stock-flow consistent approach to explicitly show results.

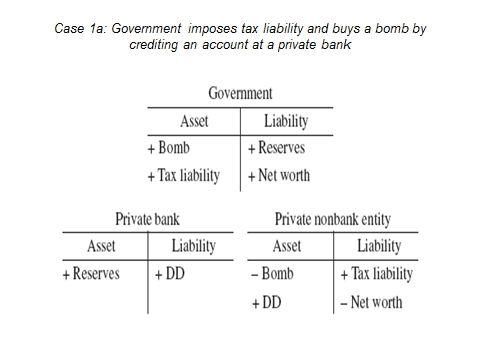

First, however, let us do the simple case, beginning with a consolidated government (central bank plus treasury) and look at the consequences of its spending. Then we will look at the real world example of the US today. Readers have asked for some balance sheet examples, so I am using some simple T-accounts here. It might take some readers a bit of patience to work through this if they have not seen T-accounts before. (Note: these are partial balance sheets—I am only entering the minimum number of entries to show what is going on.)Let us assume government buys a bomb and imposes a tax liability. This is shown as Case 1a:

The government gets the bomb, the private seller gets a demand deposit. Note that the tax liability reduces the seller’s net worth and increases the government’s (after all, that is the purpose of taxes—to move resources to the government). The private bank gets a reserve deposit at the government.

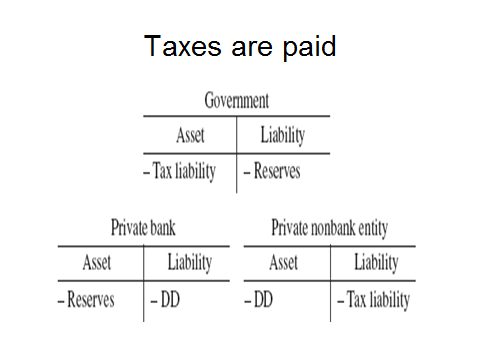

Now the tax is paid by debiting the taxpayer’s deposit and the bank’s reserves:

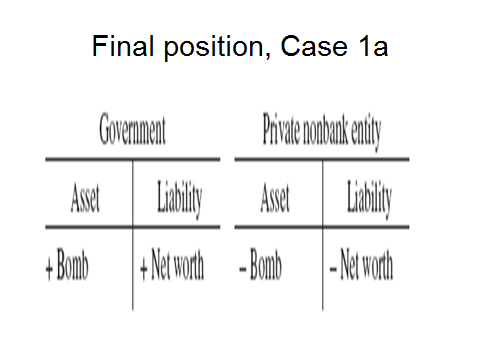

And so the final position is:

The implication of “balanced budget” spending and taxing by the government is to move the bomb to the government sector—reducing the private sector’s net worth. Government uses the monetary system to accomplish the “public purpose”: to get resources such as bombs.

Now let us see what happens when government deficit spends.

(Don’t get confused—we are not arguing that taxes are not needed; remember “taxes drive money” so there is a tax system in place but government decidesthat this week it will buy a bomb without imposing an additional tax).

Here, the bomb is moved to the government, but the deficit spending allows net financial assets to be created in the private sector (the seller has a demand deposit equal to the government’s financial liability—reserves). However, the bank is holding more reserves than desired.

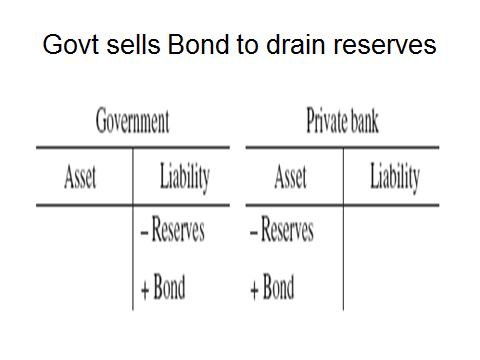

It would like to earn more interest, so government responds by selling a bond (remember: bonds are sold as part of monetary policy, to allow the government to hit its overnight interest rate target):

And the end result is:

The net financial asset remains, but in the form of a treasury rather than reserves. Compared with Case 1a, the private sector is much happier! It’s total wealth is not changed, but the wealth was converted from a real asset (bomb) to a financial asset (claim on government).

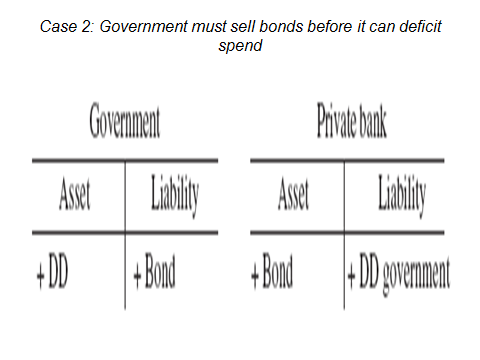

Ah, but that was too easy. Government decides to tie its hands behind its back by requiring it sell the bond before it deficit spends.

Here’s the first balance sheet, with the bank buying the bond and crediting the government’s deposit account:

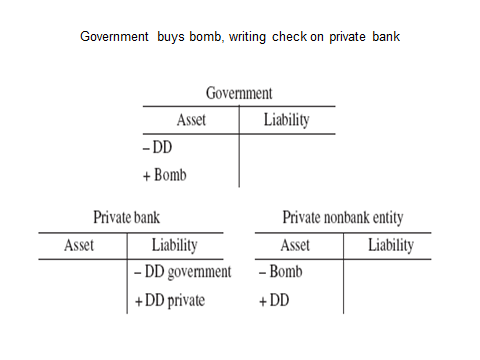

Now government writes a check on its deposit account, to buy the bomb:

The bank debits the government’s deposit and credits the seller’s. The final position is as follows:

Note it is exactly the same as case 1b: selling the bond before deficit spending has no impact on the result, so long as the private bank is able to buy the bond and the government can write a check on its deposit account.

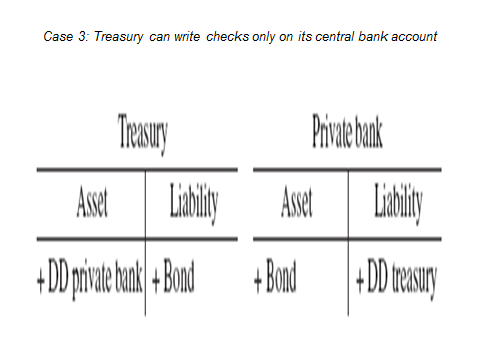

That, too, is too simple. Let’s tie the government’s shoes together: it can only write checks on its account at the central bank. So in the first step it sells a bond to get a deposit at a private bank.

Next it will move the deposit to the central bank, so that it can write a check.

We have assumed the bank had no extra reserves to be debited when the Treasury moved its deposit, hence, the central bank had to lend reserves to the private bank (temporarily, as we will see). Now the treasury has its deposit at the central bank, on which it can write a check to buy the bomb.

When the treasury spends, the private bank receives a credit of reserves, allowing it to retire its short term borrowing from the central bank (looking to the private bank’s balance sheet, we could show a credit of reserves to its asset side, and then that is debited simultaneously with its borrowed reserves; I left out the intermediate step to keep the balance sheet simpler). The private bank credits the bomb seller’s account. The final position is as follows:

What do you know, it is exactly the same as Case 2 and Case 1b! Even if the government ties its hands behind its back and its shoes together, it makes no difference.

OK, admittedly these are still overly simple thought experiments. Let’s see how it is really done in the US—where the Treasury really does hold accounts in both private banks and the Fed, but can write checks only on its account at the Fed. Further, the Fed is prohibited from buying Treasuries directly from the Treasury (and is not supposed to allow overdrafts on the Treasury’s account). The deposits in private banks come (mostly) from tax receipts, but Treasury cannot write checks on those deposits.

So the Treasury needs to move those deposits from private banks and/or sell bonds to obtain deposits when tax receipts are too low. So let us go through the actual steps taken. Warning: it gets wonky.

*The following discussion is adapted from Treasury Debt Operations—An Analysis Integrating Social Fabric Matrix and Social Accounting Matrix Methodologies, by ScottT. Fullwiler, September 2010 (edited April 2011), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1874795

The Federal Reserve Act now specifies that the Fed can only purchase Treasury debt in “the open market,” though this has not always been the case. This necessitates that the Treasury have a positive balance in its account at the Fed (which, as set inthe Federal Reserve Act, is the fiscal agent for the Treasury and holds the Treasury’s balances as a liability on its balance sheet). Therefore, prior to spending, the Treasury must replenish its own account at the Fed either via balances collected from tax (and other) revenues or debt issuance to “the open market”. Given that the Treasury’s deposit account is a liability for the Fed, flows to/from this account affect the quantity of reserve balances.

For example, Treasury spending will increase bank reserve balances while tax receipts will lower reserve balances. Normally, increases or decreases to banking system reserves impact overnight interest rates. Consequently, the Treasury’s debt operations are inseparable from the Fed’s monetary policy operations related to setting and maintaining its target rate. Flows to/from the Treasury’s account must be offset by other changes to the Fed’s balance sheet if they are not consistent with the quantity of reserve balances required for the Fed to achieve its target rate on a given day. As such, the Treasury uses transfers to and from thousands of private bank deposit (both demand and time) accounts—usually called tax and loan accounts—for this purpose. Prior to fall 2008, the Treasury would attempt to maintain its end-of-day account balance at the Fed at $5 around billion on most days, achieving this through “calls” from tax and loan accounts to its account at the Fed (if the latter’s balance were below $5 billion) or “adds” to the tax and loan accounts from the account at the Fed (if the latter were above $5 billion). (The global financial crisis and the Fed’s response, especially “quantitative easing” has led to some rather abnormal situations that we will mostly ignore here.)

In other words, timeliness in the Treasury’s debt operations requires consistency with both the Treasury’s management of its own spending/revenue time sequences and the time sequences related to the Fed’s management of its interest rate target. As such, under normal, “pre-global financial crisis” conditions for the Fed’s operations in which its target rate was set above the rate paid on banks’ reserve balances (which had been set at zero prior to October 2008, but is now set above zero as the Fed pays interest on reserves), there were six financial transactions required for the Treasury to engage in deficit spending. Since it is clear that current conditions for the Fed’s operations (in which the target rate is set equal to the remuneration rate) are intended to be temporary and at some point there is presumably a desire (by Fed policy makers) to return to the more “normal” “pre-crisis” conditions, these six transactions are the base case analyzed here (though the “post-crisis” operating procedures do not significantly impact conclusions reached). The six transactions for Treasury debt operations for the purpose of deficit spending in the base case conditions are the following:

- The Fed undertakes repurchase agreement operations with primary dealers (in which the Fed purchases Treasury securities from primary dealers with a promise to buy them back on a specific date) to ensure sufficient reserve balances are circulating for settlement of the Treasury’s auction (which will debit reserve balances in bank accounts as the Treasury’s account is credited) while also achieving the Fed’s target rate. It is well-known that settlement of Treasury auctions are “high payment flow days” that necessitate a larger quantity of reserve balances circulating than other days, and the Fed accommodates the demand.

- The Treasury’s auction settles as Treasury securities are exchanged for reserve balances, so bank reserve accounts are debited to credit the Treasury’s account, and dealer accounts at banks are debited.

- The Treasury adds balances credited to its account from the auction settlement to tax and loan accounts. This credits the reserve accounts of the banks holding the credited tax and loan accounts.

- (Transactions D and E are interchangeable; that is, in practice, transaction E might occur before transaction D.) The Fed’s repurchase agreement is reversed, as the second leg of the repurchase agreement occurs in which a primary dealer purchases Treasury securities back from the Fed. Transactions in A above are reversed.

- Prior to spending, the Treasury calls in balances from its tax and loan accounts at banks. This reverses the transactions in C.

- The Treasury deficit spends by debiting its account at the Fed, resulting in a credit to bank reserve accounts at the Fed and the bank accounts of spending recipients.

Again, it is important to recall that all of the transactions listed above settle via Fedwire (T2). Also, the analysis is much the same in the case of a deficit created by a tax cut instead of an increase in spending. That is, with a tax cut the Treasury’s spending is greater than revenues just as it is with pro-active deficit spending.

Note, also that the end result is exactly as stated above using the example of a consolidated government (treasury and central bank): government deficit spending leads to a credit to someone’s bank account and a credit of reserves to a bank which are then exchanged for a treasury to extinguish the excess reserves. However, with the procedures actually adopted, the transactions are more complex and the sequencing is different. But the final balance sheet position is the same: the government has the bomb, and the private sector has a treasury.