Originally published January 29, 2012 on the New Economic Perspectives blog.

In the previous weeks, we examined the functional finance approach of Abba Lerner. It is clear that Lerner was analysing the case of a country with a sovereign currency (or what many call “fiat” currency). Only the sovereign government can choose to spend more whenever unemployment exists; and only the sovereign government can increase bank reserves and lower (short term) interest rates to the target level. It is important to note that Lerner was writing as the Bretton Woods system was being created—a system of fixed exchange rates based on the dollar. Thus it would appear that he meant for his functional finance approach to apply to the case of a sovereign currency regardless of exchange rate regime chosen.

Still it must be remembered that all countries in Lerner’s time adopted strict capital controls. In terms of the “trilemma” they had a fixed exchange rate and domestic policy independence, but did not allow free capital flows. We have seen that domestic policy space is greatest in the case of a floating currency, but that adopting capital controls in combination with a managed or fixed exchange rate can still preserve substantial domestic policy space. That is probably what Lerner had in mind. Most countries with fixed exchange rates and free capital mobility would not be able to pursue Lerner’s two principles of functional finance because their foreign currency reserves would be threatened (only a handful of nations have amassed so many reserves that their position is unassailable). Managed or fixed exchange rates, with some degree of constraint on capital flows, can provide the required domestic policy space to pursue a full employment goal.

We conclude: the two principles of functional finance apply most directly to a sovereign nation operating with a floating currency. If the currency is pegged, then the policy space is more constrained and the nation might have to adopt capital controls to protect its international reserves in order to maintain confidence in its peg.

The US Twin Deficits Debate

Deficit hawks in the US frequently raise three objections to persistent national government budget deficits:

a) they pose a solvency risk that could force to government default on its debt;

b) they pose an inflation, or even a hyperinflation, risk; and

c) they impose a burden on our grandkids, who will have to pay interest in perpetuity to the Chinese who are accumulating US Treasuries as well as power over the fate of the Dollar.

This often leads to the claim that the US Dollar is in danger of losing its status as international reserve currency.

We have seen that national budget deficits and debts do not matter so far as national solvency goes. The sovereign issuer of the currency cannot be forced into an involuntary default. We also have dealt with possible inflation effects of deficit spending (more on that later). To summarize that argument as briefly as possible, additional deficit spending beyond the point of full employment will almost certainly be inflationary, and inflation barriers can be reached even before full employment. However, the risk of hyperinflation for a sovereign country like the US is low.

Later we will address the connection among budget deficits, trade deficits and foreign accumulation of treasuries, the interest burden supposedly imposed on our grandkids, and the possibility that foreign holders might decide to abandon the Dollar.

Let us set out the framework thoroughly examined in previous blogs. At the aggregate level, the government’s deficit equals the nongovernment sector’s surplus. We can break the nongovernment sector into a domestic component and a foreign component. As the US macrosectoral balance identity shows, the government sector deficit equals the sum of the domestic private sector surplus plus the current account deficit (which is the foreign sector’s surplus). We will put to the side discussion about the behaviors that got the US to the current reality—which is a large federal budget deficit that is equal to a (large) private sector surplus (spending less than income) plus a rather large current account deficit (mostly resulting from a US trade balance in which imports exceed exports).

There is a positive relation between budget deficits and the current account deficit that goes behind the identity. All else equal, a government budget deficit raises aggregate demand so that US imports exceed US exports (American consumers are able to buy more imports because the US fiscal stance generates household income used to buy foreign output that exceeds foreign purchases of US output.) There are other possible avenues that can generate a relation between a government deficit and a current account deficit (some point to effects on interest rates and exchange rates), but they are at best of secondary importance if not wrong.

To sum up: a US government deficit can prop up demand for output, some of which is produced outside the US—so that US imports rise more than exports, especially when a budget deficit stimulates the American economy to grow faster than the economies of our trading partners.

When foreign nations run trade surpluses (and the US runs a trade deficit), they are able to accumulate Dollar denominated assets. A foreign firm that receives Dollars usually exchanges them for domestic currency at its central bank. For this reason, a large proportion of the Dollar claims on the US end up at foreign central banks. Since international payments are made through banks, rather than by actually delivering US federal reserve paper notes, the Dollars accumulated in foreign central banks are in the form of reserves held at the Fed—nothing but electronic entries on the Fed’s balance sheet. These reserves held by foreigners (mostly, central banks) do not earn interest.

Since the central banks would prefer to earn interest, they convert them to US Treasuries—which are really just another electronic entry on the Fed’s balance sheet, albeit one that periodically gets credited with interest. This conversion from reserves to Treasuries is akin to shifting funds from your checking account to a certificate of deposit (CD) at your bank, with the interest paid through a simple keystroke that increases the size of your deposit. Likewise, Treasuries are CDs that get credited interest through Fed keystrokes.

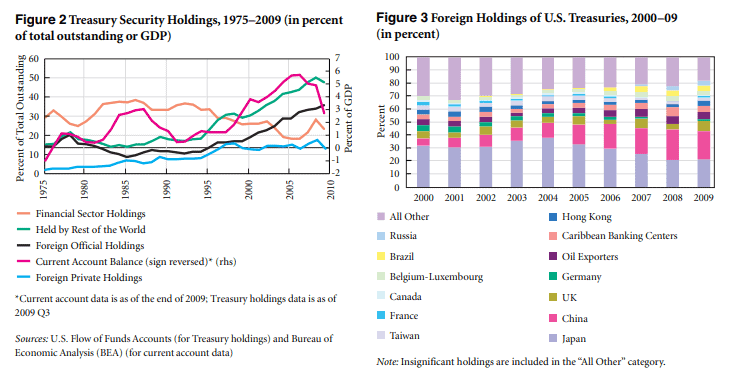

In sum, a US current account deficit will be reflected in foreign accumulation of US Treasuries, held mostly by foreign central banks. You can see the evidence here, in Figures 2 and 3:

SHOULD STOP WORRYING ABOUT U.S.

GOVERNMENT DEFICITS

Yeva Nersisyan and L. Randall Wray

While this is usually presented as foreign “lending” to “finance” the US budget deficit, one could just as well see the US current account deficit as the source of foreign current account surpluses that can be accumulated as treasuries. In a sense, it is the proclivity of the US to simultaneously run trade and government budget deficits that provides the wherewithal to “finance” foreign accumulation of US Treasuries. Obviously there must be a willingness on all sides for this to occur—we could say that it takes (at least) two to tango—and most public discussion ignores the fact that the Chinese desire to run a trade surplus with the US is linked to its desire to accumulate Dollar assets. At the same time, the US budget deficit helps to generate domestic income that allows our private sector to consume—some of which fuels imports, providing the income foreigners use to accumulate Dollar saving, even as it generates Treasuries accumulated by foreigners.

In other words, the decisions cannot be independent. It makes no sense to talk of Chinese “lending” to the US without also taking account of Chinese desires to net export. Indeed all of the following are linked (possibly in complex ways): the willingness of Chinese to produce for export, the willingness of China to accumulate US Dollar-denominated assets, the shortfall of Chinese domestic demand that allows China to run a trade surplus, the willingness of Americans to buy foreign products, the (relatively) high level of US aggregate demand that results in a trade deficit, and the factors that result in a US government budget deficit. And of course it is even more complicated than this because we must bring in other nations as well as global demand taken as a whole.

While it is often claimed that the Chinese might suddenly decide they do not want US treasuries any longer, at least one but more likely many of these other relationships would also need to change. For example it is feared that China might decide it would rather accumulate Euros. However, there is no equivalent to the US Treasury in Euroland. China could accumulate the Euro-denominated debt of individual governments—say, Greece!—but these have different risk ratings and the sheer volume issued by any individual nation is likely too small to satisfy China’s desire to accumulate foreign currency reserves.

Further, Euroland taken as a whole (and this is especially true of its strongest member, Germany) attempts to constrain domestic demand to avoid trade deficits—meaning it is hard for the rest of the world to accumulate Euro claims because Euroland does not generally run trade deficits. If the US is a primary market for China’s excess output but Euro assets are preferred over Dollar assets, then exchange rate adjustment between the (relatively plentiful) Dollar and (relatively scarce) Euro could destroy China’s market for its exports.

This should not be interpreted as an argument that the current situation will go on forever, although it could persist much longer than most commentators presume. But changes are complex and there are strong incentives against the sort of simple, abrupt, and dramatic shifts often posited as likely scenarios. The complexity as well as the linkages among balance sheets ensure that transitions will be moderate and slow—there will be no sudden dumping of US Treasuries—that would destroy the value of the financial wealth held by the Chinese, as well as the export market they currently rely upon.

Before concluding, let us do a thought experiment to drive home a key point. The greatest fear that many have over foreign ownership of US Treasuries is the burden on America’s grandkids—who, it is believed, will have to pay interest to foreigners. Unlike domestically-held Treasuries, this is said to be a transfer from some American taxpayer to a foreign bondholder (when bonds are held by Americans, the transfer is from an American taxpayer to an American bondholder, believed to be less problematic). So, it is argued, government debt really does burden future generations because a portion is held by foreigners. Now, in reality, interest is paid by keystrokes—but our grandkids might decide to raise taxes on themselves to match interest paid to Chinese bondholders and thereby impose the burden feared by deficit hawks. So let us continue with our hypothetical case.

What if the US managed to eliminate its trade deficit so that it ran a perpetually balanced current account? In that case, the US budget deficit would exactly equal the US private sector surplus. Since foreigners would not be accumulating Dollars in their trade with the US, they could not accumulate US Treasuries (yes, they could trade foreign currencies for the Dollar but this would cause the Dollar to appreciate in a manner that would make balanced trade difficult to maintain). In that case, no matter how large the budget deficit, the US would not “need” to “borrow” from the Chinese to finance it.

This makes it clear that foreign “finance” of our budget deficit is contingent on our current account balance—foreigners need to export to us so that they can “lend” to our government. And if our current account is in balance then no matter how big our government budget deficit, we will not “need” foreign savings to“finance” it—because our domestic private sector surplus will be exactly equal to our government deficit. Indeed, one could quite reasonably say that it is the budget deficit that “finances” domestic private sector saving.

Yet, the deficit hawks believe the federal budget deficit would be more “sustainable” if foreigners did not accumulate Treasuries that supposedly burden future generations of Americans. But how could the US eliminate the current account deficit that allows foreigners to accumulate Treasuries? The IMF-approved method of balancing trade is to impose austerity. If the US were to grow much slower than all our trading partners, US imports would fall and exports would rise. In fact, the “great recession” that began in the US in 2007 did reduce the trade deficit—although only moderately and probably temporarily. In order to eliminate the trade deficit and to ensure that the US runs balanced trade, it might need a much deeper, and permanent, recession. By reducing American living standards relative to those enjoyed by the rest of the world, the nation might be able to eliminate its current account deficit and thereby ensure that foreigners do not accumulate Treasuries said to burden future generations ofAmericans.

Now, can the deficit hawks please explain why Americans should desire permanently lower living standards on their promise that this will somehow reduce the burden on the nation’s grandkids? It seems rather obvious that grandkids would prefer a higher growth path both now and in the future, so that America can leave them with a stronger economy and higher living standards. If that means that thirty years from now the Fed will need to stroke a few keys to add interest to Chinese deposits, so be it. And if the Chinese some day decide to use dollars to buy imports, America’s grandkids will be better situated to produce the stuff the Chinese want to buy.

In conclusion, while there are links between the “twin deficits”, they are not the links usually imagined. US trade and budget deficits are linked, but they do not put the US in an unsustainable position vis a vis the Chinese. If the Chinese and other net exporters (such as Japan) decide they prefer fewer dollar assets, this will be linked to a desire to sell fewer products to America. This is a particularly likely scenario for the Chinese, who are rapidly developing their economy and creating a nation of consumers. But the transition will not be abrupt. The US current account deficit with China will shrink, just as its sales of US government bonds to Chinese (to offer an interest-paying substitute to reserves at the Fed) decline. This will not result in a crisis. The US government does not, indeed cannot, borrow Dollars from the Chinese to finance deficit spending. Rather, US current account deficits provide the Dollars used by the Chinese to buy the safest Dollar asset in the world—US Treasuries.

To be clear: the US Dollar probably will not remain the world’s reserve currency. From the US perspective, that might be a disappointment. In the long view of history, it is inconsequential. There is little doubt that China will become the world’s biggest economy. Its currency is a likely candidate for international currency reserve, but that is not a foregone conclusion—nor something to be feared.