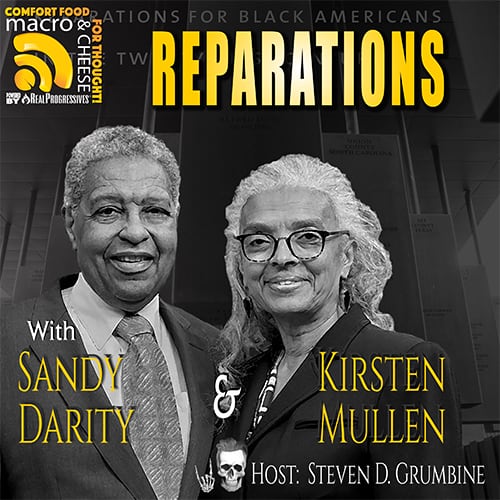

Episode 117 – Reparations with Sandy Darity and Kirsten Mullen

FOLLOW THE SHOW

156 years after being promised 40 acres and a mule, African Americans are no closer to closing the wealth gap. Kirsten Mullen and Sandy Darity join Steve to talk about their book, From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century.

This week, Kirsten Mullen and Sandy Darity join Steve to talk about their book From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century.

In recent years the debate on reparations has gained some momentum, though not for the first time, as Mullen and Darity point out. “40 acres and a mule” was among the first promises made (and broken) to black Americans since the end of the Civil War. While white families benefited from the homestead act and have continued to receive aid and preferential treatment at every level, assistance to African Americans has always been portrayed as undeserved government handouts. The abolition of slavery created new opportunities for exploitation. Our listeners are well aware that private companies utilize prison labor for pennies on the dollar.

Mullen and Darity provide examples of the racist discrimination and disenfranchisement that have poisoned the US since its founding. At every crossroad, every opportunity to do the right thing, this country has made the wrong choice, sometimes subtle, often brutal and vile.

In making the case for reparations, they focus on the staggering wealth gap. At the top of that chasm sits the wealth of corporations built on the backs of slave labor. Mullen:

You have Lehman Brothers, which began as a cotton brokerage in Alabama, for example. These were a family of brothers who initially were involved in retail trade, but they quickly realized that the real money was in buying and selling cotton. This leads to the cotton exchange in New York City. Tiffany, the iconic jeweler in New York City, was a slave owner. Most college and universities, the early ones, the elite ones, all of them benefited from donations of money from individuals who own and traded slaves or who donated land that they were able to acquire because of the slave trade.

While some reparations proposals are systemic and encompass a broader demographic, Mullen and Darity target African Americans whose ancestors were enslaved in this country. They have calculated a dollar amount to rectify the loss of intergenerational wealth that could have been created had the early promise been kept.

After you listen to this episode, we urge you to buy the book. From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century is the recipient of the inaugural 2021 Book Prize from the Association of African American Life and History and the 2020 Ragan Old North State Award for Non-fiction from the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association.

Kirsten Mullen is a folklorist and the founder of Artefactual, an arts-consulting practice, and Carolina Circuit Writers, a literary consortium that brings expressive writers of color to the Carolinas.

William A. (“Sandy”) Darity Jr. is the Samuel DuBois Cook Professor of Public Policy, African and African American Studies, and Economics and the director of the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University. Follow him on Twitter @SandyDarity

Macro N Cheese – Episode 117

Reparations with Sandy Darity and Kirsten Mullen

April 24, 2021

[00:00:01.610] – Kirsten Mullen [intro/music]

There had never been a sustained moment when white Americans were concerned about the fate of black people. You had some of the slave owners who had been concerned about the fate of the black people who they owned, but that did not necessarily extend to the fate of black people writ large.

[00:00:21.220] – Sandy Darity [intro/music]

In the southern states that formed the Confederacy, across all of them, 25 percent of all whites lived in families that owned at least one human being. And in states like Mississippi and South Carolina, the percentage ran as high as 55 and 57 percent. So there was an enormous degree of slaveholding that actually took place. It was quite commonplace.

[00:01:35.210] – Geoff Ginter [intro/music]

Now, let’s see if we can avoid the apocalypse altogether. Here’s another episode of Macro N Cheese with your host, Steve Grumbine.

[00:01:43.070] – Steve Grumbine

All right. And this is Steve with Macro N Cheese. We are going to go into reparations today, folks. I think this is a subject that whose time has come but whose time is definitely here and now. We have seen the effects of racism in society today. But this is not a current thing. This has been here since the dawning of this nation, since it’s been colonized.

And I was able to have Sandy Darity, who is a friend of the show and a friend of mine, come on a few years back. And we talked about breaking the chains, the reparations story back then. This is before this book was written. And so I asked him if I could bring him on. And he said, “Sure. But, you know, I have a coauthor too, A. Kirsten Mullen, and why don’t you bring us both on?” Absolutely.

Let’s bring them both on. So let me introduce them. Kirsten Mullen is a folklorist and the founder of Artefactual, an arts consulting practice, and Carolina Circuit Writers, a literary consortium that brings expressive writers of color to the Carolinas. We also have William Sandy Darity Jr., who is the Samuel Dubois Cooke, professor of Public Policy, African and African-American Studies and Economics, and the director of the Samuel Dubois Cooke Center on Social Equity at Duke University.

And they are the coauthors of the book we’ll be discussing today, From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century, a University of North Carolina press that was put out in 2020. And without further ado, let me welcome our guests, Sandy, Kirsten. Welcome.

[00:03:18.260] – Kirsten Mullen

Thanks for having us on.

[00:03:19.190] – Sandy Darity

Thanks for having us join you.

[00:03:20.540] – Grumbine

Absolutely. Let’s just get this out of the way. I think that folks when they hear about reparations, it causes a lot of people to have a lot of different feelings. And whether it be white people, black people, people that are older, that maybe have a different view of the world, and people that are younger. Just real quickly, before we dive in, give us a little bit of a history of what brought you to write this book and how people might perceive it.

[00:03:46.710] – Mullen

And we very much wanted to have From Here to Equality do several things. One, to talk about our shared history, both to shine a light on aspects of our history that are less known, less well known. There’s so much that we have in the atmosphere, like 40 acres and a mule.

But we don’t talk at all about the Homestead Act, 160-acre land grants that white Americans received from the federal government. We wanted to talk about misperceptions about the racial wealth gap and what is the racial gap? How large is it? How did it begin? How was it sustained? And we also wanted to provide a roadmap basically to reparations.

The heart of what we’re trying to do is look at the different paths that the US government could have taken at every stage from, as you mentioned, the founding of the republic as a slave nation, as a choice, that we made an unfortunate choice but to bring that up to the present, looking at various moments in our shared history when we could have taken a different path, one that would have led to a country where black Americans since US slavery were embraced as full citizens and also enjoy all of the rights of citizenship, which is absolutely not the case today.

[00:05:10.520] – Grumbine

No, indeed, it’s not. You start the book off standing at the crossroads, and I think this is a really important section. Break down what the crossroads are because I think that folks don’t realize how many times we’ve been at these crossroads actually over the course of history. You lay it out very clearly later on in the book, how many different times we have been at the crossroads and chosen the wrong path.

[00:05:36.200] – Darity

The original crossroad is at the formation of the Republic as Kirsten mentioned. A second major crossroad is with the end of the civil war and the opportunity to actually provide the formerly enslaved with the types of resources that would have enabled them to participate fully in American society. Kirsten mentioned 40 acres and a mule.

That was a promise that was made to the formerly enslaved. It was a promise that was not kept. And simultaneously, one and a half million white American families were allotted 160 acres of land in the Western territory. So as the nation completed its colonial settler project and those 160-acre land plots were the foundation for wealth that fell in the hands of upwards of at least 25 million living North Americans.

So that’s the foundation for the gulf in wealth between blacks and whites. But it’s associated with a fork in the road where the wrong path was taken. And then subsequent to the end of the civil war, there also was an opportunity to have full political participation on the part of blacks in the United States. That was a choice that was not made.

Instead, the black community in the United States was confronted with nearly a century of legal segregation and also a wave of white mob terrorist acts that resulted in the destruction of a number of black communities. I think there were upwards of a hundred of these terrorist attacks that took place between the end of the civil war and the beginning of the 1940s. And then, in addition, in the aftermath of World War II, there was an opportunity to universalize access to the GI Bill on behalf of both black and white returning veterans.

But the legislation was discriminatorily applied, in that it only benefited a significant number of white GIs at the expense of black GIs. And then we come to the civil rights years, or the civil rights legislation years in the 1960s where there was an opportunity to correct the entire wave of historical wrongs, but that didn’t occur either. And that’s particularly the case because there was a failure to address the huge economic disparities that existed in the United States between black and white.

[00:08:11.030] – Grumbine

It’s unfathomable to me that as a white man, looking back at history with a fearless and thorough approach to things, I’m ashamed because I see the amount of whitewashed death and punitive, cruel behavior and you really lay out the cruelty of the time. And I think the understanding of the perils at each step, they move the goalposts, they change the framing.

It’s still the same thing, though, out of slavery, into reconstruction, and back into state slavery of sorts without any protection and the government playing a huge role in the diminishing of life for black Americans. And the historical approach that you lay out, each one of the instances, they could have done this, but they chose that. And it was repeated throughout history. And then it got to the point where they weren’t even hiding it anymore. They weren’t even pretending anymore.

It was written into law, the outright hatred for black Americans. And I am flabbergasted that this has not been addressed before now, at least in a meaningful way by our government, that we have not taken direct action and fix this incredibly awful wrong. I guess we go right into the idea of the political history of the black reparations movement. This has been going on for a very long time and it’s been tried in various ways throughout history. Tell me about the political movement behind the reparations push.

[00:09:49.970] – Mullen

So are you thinking about the historic movement or the current movement?

[00:09:53.270] – Grumbine

I would say the historic movement to start. We can get to the current movement after we’ve built the case that this is a long time coming.

[00:10:02.180] – Mullen

Well, we say, as some others do, that slaves themselves were the first abolitionists . . .

[00:10:08.150] – Darity

And the first racists.

[00:10:08.750] – Mullen

And the first racists. From the time that these Africans had been captured and kidnaped and forced into labor on the continent, they were trying both to obtain their freedom and if not to be compensated for their labors and to have slavery rendered illegal. So that’s the beginning. And it’s not something that is really taught in schools. We actually have a counter-story – there were so few slave insurrections, so few incidences of resistance on the part of the enslaved.

But when you actually look at the history, you discover that there were hundreds of insurrections. There was simply a very concerted effort to suppress information in the press. Certainly slave owners were writing to each other and communicating about what they were seeing on their plantations and in their towns, but they were complicit in keeping that information out of the public eye as much as they possibly could.

One of the earliest known reparationists is Callie House, and this is a woman who had been enslaved and born into slavery who decided that she would work to petition the federal government to give pensions to the former slaves. So she was also interested in making sure that the federal government was paying pensions to blacks who had served in the Union army but also to compensate the enslaved for their many years of uncompensated labor.

She was not successful ultimately. And in fact, the federal government brought charges against her, mail fraud, saying anyone who would attract members and she was very successful. Her organization at one point had over 300,000 dues-paying members, which is quite incredible in the late 1800s. Where the federal government was saying anyone who would suggest that the federal government would pay reparations to the former slave, that was a fraudulent act.

But this is an impossible thing. And this is something for which she should be held accountable in jail. And she was. She did serve time. But we go straight line from her to the followers of Marcus Garvey. And Garvey was somewhat different in that he was an advocate of blacks going back to the continent, which is interesting because a lot of the black people who were in fact followers of Garvey had never been to the continent.

They had been born here. But that was part of his program. But he also thought the federal government should make land available to black Americans. Garvey met a similar end that Callie House did. He, too, was brought down by mail fraud charges by the federal government. Then we go from Garvey to Queen Mother Audley Moore, who took this a bit further. Queen Mother Audley Moore was much more effective in her petitions to groups like the UN focusing on reparations.

And she was probably the person who is most responsible for the various points that we think of as critical for reparations program today. She was the bridge in part to people like James Forman, who drafted the Black Manifesto in the 1960s, and he was petitioning religious communities of faith to make cash reparations not to black individuals, but supporting black media, supporting a historically black college, supporting black think tanks.

I believe the dollar amount that he had requested was $500 million dollars. He actually received a percentage of that. But this was another important moment when the reparations movement was being taken to another level. Then we have people like Spike Lee naming his film company 40 Acres and a Mule, which got a lot of people thinking, oh, this is interesting, why would he choose that title?

And that led a lot of people to do some homework. And then around 1989, we had John Conyers, Democrat from Michigan, introducing HR 40, which is legislation to create a study commission for reparations, looking at America’s involvement with slavery and trying to determine what kind of reparations the federal government should pay.

I should say, too, that earlier still David Horowitz, public intellectual, placed ads in elite college newspapers across the country in opposition to reparations. And in a lot of ways, that effort introduced the whole idea of reparations to a new generation of black Americans who were angry with him. And he was saying that reparations are a bad thing. That slavery was a good thing for black people. It humanizes them. But I used to wonder if he was really an advocate in disguise because his efforts in 2001 really got a lot of people focused on this question who had not given much thought previously.

So I think, it raised, his negative advertisement was galvanizing. Absolutely. Then we had Ta-Nehisi Coates article in The Atlantic and was it 2014 the front page, cover story, which again, that’s almost a generation after Horowitz. So you have yet another generation becoming familiar with this term. But in 2019, January, you had the most recent presidential election campaign, Marianne Williamson, one of the first politicians to deign to even utter the R-word.

[00:15:54.950] – Grumbine

Right.

[00:15:55.700] – Mullen

And I think because of her bravery that we could talk a lot about the inadequacies of the funding that she thought would be necessary to dedicate for reparations. But because she was willing to bring it up, you had Julian Castro and Tom Steyer, who were obligated to also talk about their own plans or their own desires with some kind of wealth redistribution program.

I think then-presidential candidate Joe Biden allowed that he might consider reparations for black Americans if they were also tied to reparations for Native Americans, which we have to wonder, is that the election? Does that mean he’s actually serious about both? Serious about neither? Time will tell.

But, yes, there’s been a steady focus on why the US government has refused to own its own complicity in these policies that have been detrimental to the wealth accumulation of black Americans. And we’re hoping that this is a moment where more not just extensive conversation, but more commitment to an actual reparations plan, reparations program will be put in place.

[00:17:12.800] – Grumbine

I find this to be very interesting because I spoke with a gentleman named Glenn Ford and he talked about what he called the misleadership class of black Americans. And there are many people out there that know how important reparations are, and yet they end up caving and folding into basically gatekeepers that are not committed to bringing these things to the forefront. They serve as almost a brake pedal on seeing reparations come to be.

I just find it fascinating that we’ve got so many people from so many angles that should be fighting for this that aren’t indeed fighting. Let’s go back to the book. One of the things that I thought was fascinating was the way you laid out the myth of racial equality. And I started thinking about the single-room schoolhouses and I was going through the fact that we don’t have a right to an education in this country. And some of the things they did with, OK, you’ve got to integrate schools. Fine, we’ll close the damn schools down.

[00:18:08.990] – Darity

Well, you also have to keep in mind that in communities like Farmville, Virginia, where they shut the schools down rather than desegregate, they also ensured that there was a voucher program that permitted white students to continue to go to school at private academies, while no comparable set of resources were provided to the black students. And so it was clearly a white strategy to provide white students with an ongoing opportunity to acquire years of schooling while black students were to be denied that.

[00:18:43.190] – Grumbine

You bring up wedge issue. And I think that’s a great opening for this. In reading Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow, going back to Bacon’s Rebellion and how all it takes is a couple crumbs and maybe one extra benefit, and the poor whites would separate from uniting with the blacks.

[00:19:00.560] – Darity

Well, if you go back to the colonial period, it’s more than crumbs.

[00:19:03.740] – Mullen

I was going to say, it’s not crumbs at all – an opportunity to leap into the middle class.

[00:19:09.350] – Darity

Opportunity to get land, which throughout the early years of the republic into the second half of the 19th century, it really is land that is the fundamental source of wealth for many, many Americans. It’s only in the 20th century where we get a shift towards a focus on homeownership. But prior to that, it’s land.

And in the colonial period, those whites who completed their period of indenture successfully and there was a high rate of mortality among the indentures, but if you completed your term of indenture, you were given a substantial amount of land under the head right scheme. And in many instances, those individuals became slaveholders themselves.

[00:19:52.760] – Grumbine

It’s amazing to me that this stuff happened, but yet it’s right there for you to see. I guess the next racial myth equality is 40 acres and a mule. They weren’t willing to do that. But then considering voting, the South decided we need to have these folks count towards our congressional seats. They’ve used blacks for their own purposes, and it’s never in the betterment of these individuals. It’s always just using them up. And I just cringed as I kept hearing people say, well, we elected Obama. So there is no such thing as racism. We’re all equal now. Right? We had a black president, but you go back through history. If you’re born on third base, don’t act like you hit a triple.

[00:20:37.880] – Darity

Some people are born at home plate.

[00:20:39.470] – Mullen

Exactly.

[00:20:41.840] – Grumbine

Don’t get me wrong. Some of these things you know intuitively that happened. But just the idea of acting like they got to maintain the separation. We definitely need to provide school, but we need to give a little bit more to the whites to make sure we maintain the exact same positional hierarchy that they don’t ever end up equal. That literally was what was said. Am I wrong?

[00:21:06.140] – Darity

Yeah, that’s right. That was what Andrew Johnson said. President Andrew Johnson, he’s quite blatant about that. Yeah.

[00:21:11.690] – Mullen

I have a question that maybe you can help resolve for us.

[00:21:14.540] – Grumbine

Sure.

[00:21:15.170] – Mullen

We’re curious to know why these 45 million white individuals whose families are currently reaping the benefits of the Homestead Act and we’re talking about government policy that was issued in 1862 and was in place about 60 years. Why more white people don’t talk about that in their families.

I mean, I would think that this would be those crozy stories shared around the yuletide log. You know, or the stories of great grandmother and grandfather on a wagon trail stopping at a fort for so many days. And reprovisioning and the sights that they saw. The native people who assisted them along the way [crosstalk 00:22:00]

[00:22:01.070] – Darity

Or they have to be protected by the Union military.

[00:22:07.160] – Grumbine

In the book, you actually answer this question. So I’m going to be a spoiler. The textbooks, the education of the South whitewashed history, every opportunity to make blacks look bad and whites look good was codified into the schooling.

[00:22:22.270] – Mullen

Well, Steve, why would that story, though? The Homestead Acts didn’t have anything to do with black people. Well, really

[00:22:28.090] – Darity

Well, they did.

[00:22:28.090] – Mullen

The way they were administered had nothing to do with black people. So I’m asking, why do you think white people don’t talk about that piece of their history?

[00:22:37.360] – Grumbine

I think honestly because that’s a handout. This is the very thing that they complain about. And I think honestly, that they don’t want to be seen in their own perverse way as moochers. That’s the best I can come up with. Either that or it’s just not taught properly.

[00:22:51.850] – Darity

Well, and I think the other thing is, the way in which it’s been portrayed in the movies, in particular, is kind of this heroic trek into the West in wagons.

[00:23:01.750] – Grumbine

Rugged individualism

[00:23:03.400] – Mullen

Don’t you think that would be a story that they would lionize?

[00:23:06.220] – Darity

Well, indeed, you would think so. But I think people don’t really want to talk, as Steve is suggesting. They want to talk about the fact that the land was essentially a gift or a handout. They prefer the story to be one of well, we went out and we put a grubstake on this plot of land, and that’s how it became ours, not that it was something that the federal government actually gave them.

[00:23:30.550] – Grumbine

It was confiscated from indigenous people and then handed over to another welfare state. Right?

[00:23:36.590] – Darity

Right.

[00:23:37.090] – Grumbine

The white welfare state. Since you threw that question at me, let me bring it back. There was an awful lot of wrangling during this period of understanding the balance between the races and the radical Republicans were fighting for not only emancipation but for the rights of man to be seen as universal. I guess my question to you is, given that there were some white people out there that were seeing this, at least at some level, more clearly than others, I am curious how they got shut down in this process?

It seems to me like there is an intentional diminishing of the radical Republicans in our history lessons. I think the first time I ever really got that full picture was watching the movie Lincoln. Why do you suppose that is so whitewashed out of history and completely overlooked in my opinion?

[00:24:35.860] – Mullen

You know, it’s interesting. I remember learning about the Morrill Act and also learning about 40 acres and a mule. But no one really put those two things side by side in my history classes, either in high school or in college. I think I would have paid a lot more attention if that had been the case if I had known that black people basically did not benefit from the Homestead Act and that they also didn’t get the 40-acre land grant.

But I think there were a lot of things going on at the time. You had these terrorist attacks that were rampant. Initially, Ulysses Grant was in support of the radical Republicans and their allies, and he was sending the federal troops to protect them all across the south. But I think several things began to happen, but taxes certainly didn’t diminish, and Thaddeus Stevens dies.

And he was in a lot of ways the heart of the radical Republicans. And then we have a financial crisis that occurs. So white attention is diverted away from these attacks and they’re thinking about their own pocketbooks. Plus there has never been a sustained moment when white Americans were concerned about the fate of black people.

You had some of the slave owners who had been concerned about the fate of the black people who they owned, but that did not necessarily extend to the fate of black people writ large. So this was a very different kind of exercise, a very different kind of position. One of the startling things for me was we need to understand all of the different shades of an abolitionist.

You know, on the one hand, we might be thinking these were the guys in the white hats who believe that slavery should be outlawed, but also believe that blacks should be at least black men should be given the franchise, that they should be allowed to own property, serve on juries and such that they should be formally educated at the expense of the state. Well, that was not at all the case for many abolitionists.

Quite a few of them were very happy to have black people no longer being slaves, but they really weren’t at all interested in having them become literate. Many of them wanted to jettison black people to the continent and not have them be in the United States at all. The assumption seemed to be since they were no longer of value as human chattel, then we would just rather they disappear altogether. So that was a big part of it. We didn’t have this monolith of sentiment among even the white so-called liberals at the time.

[00:27:16.690] – Darity

The first abolitionists were the enslaved, that’s a counter to the image that most people have of thinking about abolitionists as largely white people. And as Kirsten just pointed out, among those whites who were abolitionists, there was a wide variety of attitudes toward the Negro, if you will, and not all of those attitudes were salutary.

[00:27:41.200] – Grumbine

You did something in the book that I think is masterful. You would refer to them as the kidnapped human beings, the human trafficked human beings. You use terminology that specifically got away from placing these people as slaves. They were not slaves. They were human beings that had been stolen and brought to a foreign land.

They thought of them as property. And you go into tremendous detail. But when I was reading what you had written, I kept going back to the very first chapter of C.L.R. James, The Black Jacobins, where he lays out in such graphic detail the kinds of abuse that the slaves in Haiti or Saint-Dominque at the time were put through.

[00:28:25.270] – Darity

Yes.

[00:28:25.580] – Grumbine

And just the idea of putting gunpowder in the rectum of slaves and blowing them up from the inside, burying them up to their head and slathering them with sugar so they would get devoured by flies, the things that were done were so horrific.

And then I read the stuff that happened in the United States and all this stuff is going on in parallel, the Louisiana Purchase and Haiti, all the different colonies in the West Indies. I don’t think people realize just how horrible this was. And when we talk about the myths of racial equality, they were able to kill blacks without any fear of reprisal.

[00:29:02.230] – Darity

Between 1865 and 1895 one of the last black representatives in Congress, Robert Smalls from South Carolina estimated that 53,000 black people were murdered by whites in these types of acts of terrorist violence.

[00:29:22.410] – Grumbine

It’s just unfathomable to me that people could not understand how unequal society was and has continued to be, and you detail it both through reconstruction, through the industrial revolution, through the war era, and up to present times. There has been improvements in some ways, but there has been so much more just shifting the goalpost in terms of the framing, the words we use. Can you explain to me who is the ones that benefited from slavery?

[00:29:54.940] – Mullen

I mean, certainly, it’s white people who reap the benefits. There are some reap more and some more directly than others. But absolutely, the people who themselves enslaved black people benefited directly from the profits of their labors, all kinds of financial concerns and corporations were built on the backs of enslaved labor.

You have Lehman Brothers, which began as a cotton brokerage in Alabama, for example. These were a family of brothers who initially were involved in retail trade, but they quickly realized that the real money was in buying and selling cotton. This leads to the cotton exchange in New York City. Tiffany, the iconic jeweler in New York City, was a slave owner. Most college and universities, the early ones, the elite ones, all of them benefited from donations of money from individuals who own and traded slaves or who donated land that they were able to acquire because of the slave trade.

Connecticut is a state that people don’t typically associate with slavery. But Connecticut became a tremendous location for textile mills. And these were mills for milling cotton, and it was slave-grown cotton that they were milling, but over a hundred textile mills all across Connecticut, that would not have been possible if not for forced slave labor. Slavery was a global economy.

You didn’t have to own a slave to benefit from it. Say your family made barrels or you made the mass of ships that were slave-carrying prisons or you were a metal worker that produced shackles or those hideous iron collars that had spikes, some of them 12 inches long to mark a recalcitrant enslaved person.

Or you were Brooks Brothers, the clothier that made suits and gorgeous gowns and dresses for the wealthy classes, but also tens of thousands of plantation clothing, of course, slave cloth. These are the people who clothed all of the hundreds of thousands of black enslaved people across the south at a profit. Newspapers, The Hartford Courant is one of the newspapers that has existed from the antebellum period, USA Today and Gannett has its history in the slave movement.

[00:32:30.520] – Darity

Advertising

[00:32:31.840] – Mullen

Advertising was absolutely tied to slavery. And not only did they advertise for runaways, rewards for runaways, but they also advertised jobs for ship’s captains and crews and people who provisioned ships. It was a huge enterprise and it made a middle class and upper-income life possible for many, many, many white people.

[00:32:54.790] – Darity

Like to mention that there’s a couple of books that people might be interested in reading that are connected to the observations that Kirsten just made. One is the best study of the relationship between America’s elite universities and the slave trade and slavery, which is Craig Steven Wilder’s book called Ebony and Ivy. And with respect to the global nature of the cotton sector, Sven Beckert’s excellent book, Empire of Cotton is relevant.

I’d like to add also that I think people neglect frequently the significance of non-plantation slavery, what we might refer to as domestic slavery, which essentially freed up the time for many, many households from having to take care of a host of domestic responsibilities. They could do other things and they could accumulate more wealth in doing those other things by exploiting unpaid black labor.

And I think that there was also a companion tendency to underestimate the magnitude of slave ownership in the United States. So frequently we hear from folks who are critical of our book that only one percent of white Americans owned enslaved people. That’s an absolute lie. It’s a fiction. The figure is closer to eight percent of all individuals and white families were in families that owned slaves.

And that figure is eight percent solely because at the point of the start of the civil war, the vast majority of states in the north did not maintain legal slavery. But in the southern states that formed the Confederacy, across all of them, at minimum, 25 percent of all whites lived in families that owned at least one human being. And in states like Mississippi and South Carolina, the percentage ran as high as 55 and 57 percent.

So there was an enormous degree of slaveholding that actually took place. It was quite commonplace. And in some of these families, it was one individual, but that one individual was exploited labor. And so the benefits that were extracted from the system of slavery were quite widespread. Even on the part of nonslaveholders, but especially on the part of those folks who were slave owners.

[00:35:37.070] – Mullen

When you look at states like Connecticut in the 18th century, slavery was still legal there. The majority of white corporations own at least one black life. It’s a piece of our not knowing our history.

[00:36:02.970] – Intermission

You are listening to Macro N Cheese, a podcast brought to you by Real Progressives, a nonprofit organization dedicated to teaching the masses about MMT or Modern Monetary Theory. Please help our efforts and become a monthly donor at PayPal or Patreon, like and follow our pages on Facebook and YouTube and follow us on Periscope, Twitter, and Instagram.

[00:36:52.030] – Grumbine

One of the things that I think is often brought up as a white person that has heard tropes within white society, I didn’t own slaves. Why in the world should I care about this? But I think as you laid out, that eight percent owned slaves, there are benefits that exceed just owning slaves and extracting their labor, not just the ones that own slaves but by all that are not understood by those people. They don’t realize how they benefited. Can you talk a little bit about the nonslave owners and the benefits they might have reaped from this?

[00:37:26.520] – Mullen

Certainly a lot of roads led to slavery, the whole process of policing black bodies was huge, whether one was hired directly as an overseer by a plantation owner or someone who was hired to patrol the roads. Lots and lots of people were engaged in this business of keeping an eye on black people, making sure that they were not congregating, possibly having conversations that might lead to some kind of insurrection and getting paid to do so.

We know, too, that after the institution of slavery was no longer legal, there were all kinds of systems put in place, systems that made it more likely that black men, especially during the harvesting times or when companies like lumber companies or coal companies or the railroad companies needed large number of laborers to do their work.

Local sheriffs, justice of the peace, could find all kinds of reasons to dragnet black men, particularly into their sphere, into jail they would go and every single person who touched them in this process extracted a fee. The person who reported a black person who appeared to be on the streets, not gainfully employed, the person who arrested them, the person who put that information in a formal log for the county, the person who put them in jail, the person who brought water, food, all of these people extracted a fee.

And whether you were guilty or not, you were required to pay this fee. And if you didn’t have the money, then you would go to jail. And what often happened is a company or individual would come and say, I understand Steve Grumbine is in jail and that he owes $6.40 to the county. I’ll pay his $6.40 and now he will work for me. But I get to decide how long he will work for me to work off that $6.40. He might work off that $6.40 for about six months.

[00:39:37.860] – Grumbine

Oh, my goodness!

[00:39:37.860] – Mullen

And you might end up doing that not in your home state, but in the state of Alabama, working for Bessemer Steel, for example. And if you survived it, then you had a chance to come back home. But many people didn’t survive those kinds of arrangements. Some of them at least during slavery, the person who claimed to own you had an interest in your well-being. But once you were caught up in this convict leasing system, there was no one who was making any kinds of pleas on your behalf.

[00:40:11.520] – Darity

One of the most horrific cases we report in the book is Sugarland, Texas, so sugar production that relied upon convict leasing.

[00:40:21.210] – Mullen

In that case, two partners who had been Confederate officers leased the entire prison population to work in their sugar cane fields.

[00:40:31.500] – Grumbine

Even though I’ve read this book five times, every time I hear about these things, I’m just so ashamed of this history that we have and that we haven’t rectified it. But we talked a little bit about Thaddeus Stevens and his push with the radical Republicans for both emancipation and freedom and equality. And I guess let’s jump to Reconstruction because you mentioned how when there was slavery, at least the slave owner had some vested interest in protecting his, quote, unquote, “human property.”

But once Reconstruction happened, you had a lot of bitterness. And with Lincoln’s death, Andrew Johnson, who was absolutely pro-slavery, eradicated the gains that were had during that time period and allowed for things to go into a more awful direction. Can you explain what happened during this reconstruction era?

[00:41:25.590] – Darity

Although the enslaved people were of value to the slaveholders for the purposes of maintaining control of the system, they frequently destroyed them physically or took their lives.

[00:41:40.890] – Grumbine

Yes.

[00:41:41.760] – Darity

So despite the fact that there was a financial benefit to keeping them going for the purposes of keeping the system going, they would in fact do horrific things to some of them.

[00:41:54.270] – Mullen

Made an example for the others.

[00:41:57.100] – Darity

But the reconstruction era was indeed one of these critical forks in the road, perhaps the most critical fork in the road where there was an opportunity that was really advanced by the radical Republicans in particular, to bring the formerly enslaved into full citizenship in the United States. And that did not occur.

And Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor after Lincoln was murdered, was instrumental in the process of ensuring that Reconstruction did not proceed in such a way that the formerly enslaved were brought into full citizenship. So he’s the person who reversed the beginnings of the allocation of land under the proposed 40 acres grants process.

He’s the person who ensured that the former Confederates came back into power in the states of the South, whereas the radical Republicans were attempting to engage in something that we call lustration, which is to exclude them as traitors from renewed participation in the electoral process in the states that had been in rebellion. And so the entire process of Reconstruction gets reversed and the beginnings of that reversal are strongly associated with the decisions that Andrew Johnson made.

[00:43:19.230] – Grumbine

I think it’s important to state here blacks served in the military. They thought that by fighting in the war that that would earn them their freedom. And this was one of those truths about the efforts that blacks made to try to earn their freedom and try to gain a safe place in society.

[00:43:39.120] – Mullen

Well, certainly manumission did come, but the safe place, no. There’s never been a safe place in society for black people in this country.

[00:43:47.010] – Grumbine

And it’s still that way to this day. George Floyd, rest in peace. There’s so many names that are just forgotten. There’s something you talked about that I think is worth discussing. The Seven Mystic Years from 1866 to 1873. Let’s talk about that for a few minutes.

[00:44:06.110] – Mullen

So this is the term that W.E.B DuBois gave to this period of Reconstruction, this seemingly magical, mystical moment when black and white men did co-govern, when there were legal prescriptions that provided the vote to black men, there were a list of demands that the states that had seceded from the Union were to meet in order to regain their good standing. Among those were guaranteeing the rights of black men to vote, allowing black people to be on juries. Creating public education basically.

This is something that had not been available even to white people in the South and then forging new constitutions that erased the black codes. These were those interlocking dozens and dozens of laws that constrained all of black life, black mobility, the kinds of work that black people could engage in, the conditions under which they could engage in a contract, could break a contract.

But for this seven-year period, you had a lot of evidence of the program working. But there were many people who were not pleased to see this. One of the other tenants was that the Confederates, who had not sworn allegiance to the US government, were not allowed to participate in the government across the south, and they were not happy about that.

And you began to see in places like Coushatta and Colfax, Louisiana and New Orleans, horrible terrorist massacres on these black elected officials and their white allies. The former confederates were not going down easy. They did not say we lost the war, we to have to take our lumps. Now it’s interesting that we talk in From Here to Equality about this moment when white southerners were prepared for the kinds of changes in the way business was conducted across the south.

They were looking forward to working through that so that they could emerge on the other side of it as citizens in good standing. And if that meant that they would have to co-govern with black people, that that meant that black people would be allowed to own property and to enter contracts with white people just as whites were they were prepared to do that. They waited and they waited and the moment never came.

And then you have Andrew Johnson reinstating these former seceded states long before they had made any of the changes that had been demanded. And the southern states said, “Wait a minute, you mean we’re not going to be punished for having lost the war? We’re not going to be disallowed to participate in elections? We’re going to be allowed to put our own candidate forward for elections?” They thought, “Well, yippee! Good for us.” One of them is quoted as saying, “This was more than we had dared hope for.”

[00:47:16.080] – Grumbine

If I’m not mistaken, the one thing Thaddeus Stevens was really up in arms about and Lincoln had made sure of was that the Confederates were not allowed to hold office.

[00:47:26.970] – Mullen

Right.

[00:47:28.080] – Grumbine

But that got washed away as well. So they allowed the very people.

[00:47:31.540] – Darity

Yes.

[00:47:31.980] – Mullen

Yes.

[00:47:33.120] – Darity

Yeah, absolutely.

[00:47:33.960] – Mullen

And some of them never, ever owned their part in the war, and they never pledged allegiance to the United States.

[00:47:41.070] – Darity

I want to add that Kirsten mentioned Coushatta, Louisiana and Colfax, Louisiana. Frequently people say that the horrendous massacre that took place in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898, that’s the only municipal coup d’etat in the history of the United States. That’s not true. In both Colfax and Coushatta you essentially had the overthrow of the elected officials.

What’s true in all three cases is the elected officials consisted of collaborative groups of blacks and whites under the rubric of the Republican Party or in some instances under the rubric of a Populist plus Republican Party. So all the municipal coup d’etats were designed to overthrow any significant influence of the black electorate. But it wasn’t just in Wilmington. It really starts in the immediate aftermath of the civil war.

[00:48:39.800] – Grumbine

Wow. Let’s talk about Jim Crow for a minute. It’s very important as it plays into demonstrating beyond slavery, the impacts that black Americans have suffered at the hands of this government and white people as a whole. Can you talk about the Jim Crow era and beyond?

[00:49:01.500] – Mullen

We gave the Jim Crow era its start somewhat earlier than many people do when you’re looking at these black codes that in some cases were even more severe than the codes were from the early, early days of the republic. This was really a determined effort to get as close to slavery as possible in a lot of these states.

There’s no public space where black people were free to be without the permission of some white person of power and what was different, I think Allan Tellis talks about this. How before you were subject to the whims of the person who claimed to own you, but in Jim Crow, even a white child could say something that could land you in jail.

[00:49:50.180] – Darity

Or get you lynched.

[00:49:51.810] – Mullen

Or get you lynched. So there were just so many dangers for black people and so few places of any kind of refuge. This is a point when black people who had been engaged as laborers on farms and plantations most likely ended up as sharecroppers. And they were forced to enter into year-long contracts. This is one of the interesting things about the Homestead Act.

Even if the federal government had been disposed to make the Homestead Act land grants available to black people because the Homestead Act actually started in 1862 while the Civil War was still underway. Most black people could not take advantage of it because they were tied up in these year-long contracts to most likely people who formerly had owned them.

And so they weren’t free to leave and take advantage of any opportunity that might happen. One of the things that we talk about in From Here to Equality is these different ways to measure the value of a black person’s life. So all through this period all across the country more interested in black people. There is a strike in Alabama where we learned that the per capita allocation for white children in a public school was $15.

It was 32 cents for black children. On the one hand, you want to say, “Well, why do they even bother to spend 32 cents on the black students?” But I suspect this was something that we learned about in a newspaper article in The Liberator. But my guess is that local whites would say, “Well, see? We gave you something. We didn’t just leave you in the cold.”

[00:51:31.490] – Grumbine

That is what I see happening even to this day. They always throw you just a couple of crumbs and that should sedate you. And I can only imagine dating back to this time where the power dynamics were so absolute. To me, it’s just unbelievable.

[00:51:47.030] – Mullen

Well, and we were so excited to learn more stories of these individuals in these rural communities who decided to stand up and to try to vote, to try to put forth black candidates. How amazing was that in that time? We look at cities like Oklee, Florida, whereas the election was approaching in 1920 and local whites began to drive through the black community at night, terrorizing folks and letting them know that they did not expect them to be voting.

But some of these black people went ahead and went to the polls and then the local whites burned their community to the ground. I can’t imagine what kind of courage it would take knowing that that had happened in Oklee for black people in other parts of Florida to exercise their franchise and yet they did with disastrous results, certainly in that period. I think Sandy mentioned just the incredible number of terrorist attacks that occurred during this long stretch of Jim Crow.

But the summer of 1919, you know, really more like 18 months, not just the summer, where at least 35 such attacks occurred: Elaine, Arkansas, Omaha, Nebraska, Chicago. They weren’t just confined to the south. White people across the country were determined not to coexist in public spaces with black folks. They didn’t want to share swimming pools. They didn’t want to share the ocean with black people in Chicago. [crosstalk 00:53:31] They absolutely. Yeah, right. Exactly. Thank you.

[00:53:35.360] – Grumbine

The whole separate but equal thing. Right?

[00:53:38.780] – Mullen

But they certainly didn’t want to share train cars or streetcars, or restaurants where it is often said often times the black communities that are well known to some of us, like Tulsa, Oklahoma, this is the Greenwood district where the black community lived, but they’re known to us because white people burned it to the ground. They were too prosperous to be allowed to continue.

[00:54:04.340] – Darity

If I could say, the racial wealth gap is the best economic indicator of the cumulative intergenerational effects of white supremacy in the United States. And that’s why we fixed that as the target that should be central to any reparations plan. And that’s an ambitious target, because if you were going to bring the black share of wealth, which is currently about two percent or less than two percent, the black share of the nation’s household wealth into consistency with the black share of the nation’s population and specifically black Americans who are descendants of persons enslaved in the United States, constitute about 12 percent of the nation’s population.

If you’re going to raise that black share of wealth from two percent to 12 percent, it would require an expenditure somewhere in the vicinity of 12 to 14 trillion dollars. And that’s something that should be a central objective of the reparations plan. And we also think that this is a reparative act that must be specific to black Americans who have ancestors who were enslaved in the United States because that’s the community whose ancestors were deprived of the promise of 40 acres upon emancipation.

And it is the community that has borne the brunt of a series of atrocities that are unique to the American experience, including the way in which slavery ended by a civil war in which the enslaved themselves contributed to the ending of slavery by their own participation in the Union army. The timing of when slavery ends in the 1860s and the very unique character of the types of atrocities that took place after slavery was over. Those are all very specific to the US experience. Therefore, it is black folks who are specific to the United States who have a claim for restitution from the United States government.

[00:56:13.000] – Grumbine

As a Modern Monetary Theory guy, the idea of reparations before I understood MMT, where will we come up with this money? I couldn’t imagine where all this money would come from. But now that I understand federal finance, there should be absolutely nothing other than bigotry that would prevent us from executing not only cash reparations but also a systematic changing the way things are done as well.

I believe you said that reparations are multi-part, and while there is certainly a sizable and very intentional need for a cash reparation, what else would come about with this reparations program that you are advancing?

[00:56:56.710] – Mullen

I want to say first, we wholeheartedly agree with you that certainly in the wake of the Cares Relief Act and the secondary funds that have gone out to the American public, that the US government absolutely has the capacity to fund a reparations program. It’s just the question of whether we have the will to do so. Whether your listeners will say, “Well, yes, we’ll agree with you and us,” and say, “We’re going to work hard.

We’re going to lobby and petition Congress for a full scale reparations program for black American descendants of US slavery. But I think we believe that direct payments should be to those eligible recipients. And we can talk about that a bit are key. But we know that because we’re talking about wealth building, there are a variety of ways that those payments could be made.

They could be in something a little less liquid, perhaps an endowment account, a trust account, maybe even stocks or bonds potentially. But a significant part of the bill needs to be allocations of direct payments to individuals who, as Sandy was saying, are direct descendants of individuals who were enslaved in the United States and who self-identify as black African American Negro and have done so for at least 12 years before the onset of any reparations program initiative.

But we think that if on average, black American households receive, what, $840,000, that would be a systemic change. They would have a greater capacity to engage in political life than they do currently. Not only would one have the opportunity to purchase a house in a higher identity neighborhood with better schools, but also have access to higher quality of medical care, to good legal counsel.

There are a host of things that wealth enables one to do. Wealth is a cushion against job loss. And job loss almost always means the loss of health insurance. So having wealth enables one to weather the storms more so than when one does not have wealth. We know that 25 percent of all white families have wealth of at least one million dollars and only four percent of black households.

So it would be a huge game-changer for black Americans of US slavery to have access to this kind of funding. Basically, 12 to 14 trillion dollars is what we estimate the lower end of the bill to be. And absolutely, we would anticipate that this would be a game-changer in terms of how black people are able to engage in social and political life in this country.

[00:59:49.510] – Darity

We like to say that reparations of this type would give black American descendants of US slavery the material conditions for full citizenship that has been so long denied.

[01:00:01.110] – Grumbine

I like the material conditions. That’s where I was about to go with this. I know that there are some criticisms of your plan. Why don’t you let us know some of those real quickly and then we can go ahead and debunk them and move on?

[01:00:17.220] – Mullen

Well, the first is what we just talked about. You know, where will the money come from? Many people think that it would require a tax or it would require that white people make payments from their own savings. Some will say, “Well, why should we have to pay? My family didn’t enslave anyone.” To which we would say, “Are you sure? Have you done that research? And are you aware of your family’s potential involvement in the slave trade?”

[01:00:42.060] – Darity

And we also like to ask, “Well, did your family benefit from the Homestead Act, or did your family benefit from the GI Bill?” Because all of these things were discriminatorily applied. So there is a sense in which you might have benefited from a government handout of some sort or what Ira Katznelson calls ‘affirmative action for white people.’ So that’s a set of questions that I think people should ask about their personal family history.

[01:01:09.100] – Grumbine

We’re often talking about class struggle and the working class. I’m just curious as to whether or not you feel that other things would pile into reparations or if you really are focused purely on the financial aspect of it.

[01:01:24.490] – Mullen

There are a host of things that need to happen and that would make all of our lives better. Those of us who are pushing for full citizenship for black Americans since US slavery. Malcolm X said if someone stabs me in the back and the knife goes in nine inches, if you pull the knife out three inches, that provides some relief, but I’ve still got six inches in my body.

If you pull it out three more inches, even greater relief, but I’m still suffering. And even with the knife is pulled out completely, the wound is still open and hasn’t healed. And we view these kinds of programs, whether they are racial equity programs that a city might initiate along the lines of what we’re seeing in Asheville, North Carolina, for example.

These are basically programs that these cities should have been engaged in all along. They are admitting that they systematically excluded black people from contracts, from amenities, from sitting on committees and commissions, all kinds of situations where these kinds of benefits were an opportunity. That’s a racial explanation. That’s like pulling the knife out about three inches.

Now, if you are going to create some kind of a housing voucher program like the one that Evanston, Illinois has created and unfortunately mislabeled as reparations, that’s a similar kind of effort to pull the knife out somewhat. If you’re talking about colleges and universities that are offering scholarships to black American descendants of US slavery, although usually what we’ve seen with these colleges and universities is a focus on their blacks. Their enslaved black people.

Let’s just take Georgetown, for example. Here is the Catholic diocese basically creating this model for all of its congregants saying that slavery is great. It’s perfectly fine for you to kidnap people and force them to labor against their will and without compensation. This was not something that affected only those 272 folks who were sold in 1838 to help relieve them from their debt.

This was something that Catholics and others, not just in Maryland but across the country, were watching. And it helped to cement this institution as something that was quote-unquote “good.” It is for the public good. So in our minds, all of these things fit into this notion of relieving the experience of the wound, but none of them, individually or even collectively will eliminate the racial wealth gap, which would be healing the wound.

[01:04:08.880] – Darity

Pulling the knife out would include strategies to eliminate anti-black police violence.

[01:04:15.060] – Mullen

Exactly.

[01:04:15.060] – Darity

But that’s not the same as compensating people for the extended damages that have been created by anti-black police violence. And we like to argue that if we start thinking about this array of damages in a systematic way, rather than just enumerating them one by one, this is captured well by the black-white wealth gap. And that’s why we say that has to be a central focus of this type of initiative that we’re calling reparations. So we have to pull the knife out and we have to heal the wounds.

[01:04:48.320] – Mullen

Exactly.

[01:04:48.870] – Darity

And healing the wound is reparations.

[01:04:50.910] – Mullen

I was going to say, another example with Evanston, Illinois, where they are targeting families that were discriminated against in the housing market by the city between 1919 and 1969. What they’re offering is $25,000 vouchers, basically, that can be used toward the down payment on a new house or for maintenance repairs on an existing home.

And our question, first of all, is how far that $25,000 as a down payment going to go when the average price of a house in Evanston is $423,000. But no one is making an attempt to talk about how much value, how much wealth those black families lost across that 50 year period because their homes were arbitrarily appraised at a lower value than those of their white neighbors next door in an adjacent neighborhood.

That’s not part of what’s being discussed. So these efforts are useful. Hopefully, they will produce goodwill in their communities, but they’re not going to eliminate the racial wealth gap. And that for us is an essential part of any true reparations program.

[01:06:00.690] – Grumbine

I would be remiss in not mentioning Sandy’s work on the federal job guarantee with Darrick Hamilton and others. I am a huge champion of the federal job guarantee. I think it’s a very vital stabilizing program that will help the entire nation. But I see this predominantly helping those who have been stuck in generational poverty and along with reparations. I would like to note as we close out, what are your thoughts on the combination of a federal job guarantee as putting the salve on the wound after you pull the knife out of the back?

[01:06:34.200] – Darity

Oh, I’m an enthusiast for the federal job guarantee, but I’m also a realist about its limitations. And I’ve actually heard Representative Ayanna Pressley on a number of occasions say that the federal job guarantee would close the racial wealth gap. Well, that’s absurd because the federal job guarantee is focused on people’s income via their earnings and income and wealth are not equivalent by any means.

There’s nothing about the federal job guarantee that would have any significant effect on an individual’s wealth holdings. There is a lot that’s important about a federal job guarantee in terms of providing people with protection from falling into poverty or being exposed to unemployment. But I think it’s a far cry to claim that it has any kind of significant consequences for the racial wealth gap.

And again, keeping in mind that it’s a 12 to 14 trillion dollar bill at minimum, I would insist that anybody who claims that they have a policy in mind that would close the racial wealth gap, that they demonstrate that it would generate that magnitude of change in the wealth holdings of black Americans.

[01:07:46.530] – Grumbine

That’s absolutely a slam dunk for me. Thank you both so much. Folks, if you get a chance, please pick up this book. It is absolutely must reading. If we could have kept on four or five hours, we still wouldn’t covered everything in this book. It’s just that thorough. Sandy, Kirsten, thank you guys so much for joining me today. Is there anything that you would like to leave with the listeners as we part here?

[01:08:10.290] – Mullen

We would like to urge your listeners to lobby and petition Congress for a national reparations plan for black American Descendants of US slavery. Our hometown city council in Durham, North Carolina did exactly this. They unanimously passed a resolution that advocates for reparations. They speak very directly to the importance of eliminating the racial wealth gap.

They also affirmed payments should be made directly to the eligible recipients. And they also point to some of the shortcomings of HR 40 as written, which we think is tremendous. I mean, this is an opportunity for individuals, but also formal and informal organizations to stand up and be heard. All of us have a voice and all of us have agency. And Congress is listening.

[01:08:59.940] – Grumbine

Fantastic. Well, thank you both very much. I appreciate it. I hope we can have you again to be guests soon.

[01:09:06.360] – Mullen

Thank you so much, Steve, for having us.

[01:09:08.650] – Grumbine

Got it.

[01:09:10.120] – Darity

You take good care.

[01:09:10.120] – Grumbine

All right, all right, folks, well, this is Steve Grumbine with Macro N Cheese. We’re out of here.

[01:09:20.650] – Ending credits

Macro N Cheese is produced by Andy Kennedy, descriptive writing by Virginia Cotts, and promotional artwork by Mindy Donham. Macro N Cheese is publicly funded by our Real Progressives Patreon account. If you would like to donate to Macro N Cheese, please visit Patreon.com/realprogressives.

Mentioned in the podcast

Bio of Kirsten Mullen

Remembering Callie House, an Early Reparations Advocate

My Reparations Bill – HR40 by Cong. John Conyers

Ten Reasons Why Reparations for Blacks is a Bad Idea for Blacks—and Racist Too by David Horowitz (2001)

United States required to account to Osage Headright Holders

Lehman Brothers – A Fall from Grace

Book Review: “Ebony and Ivy” – Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities by Craig Steven Wilder

‘Empire of Cotton,’ by Sven Beckert

The Propaganda of History by W. E. B. Du Bois

When Affirmative Action Was White – An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America by Ira Katznelson

Related Podcast Episodes

Related Articles