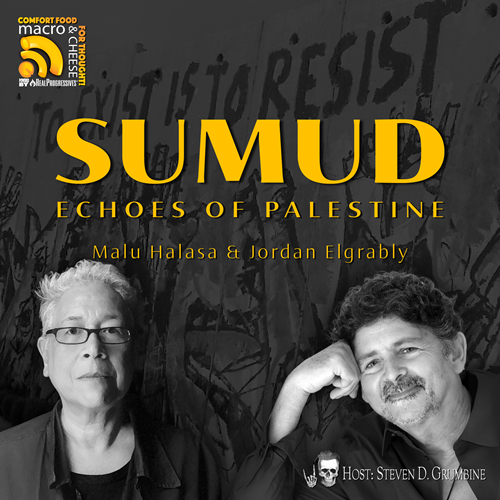

Episode 312 – Sumud: Echoes of Palestine with Malu Halasa & Jordan Elgrably

FOLLOW THE SHOW

Guests Malu Halasa and Jordan Elgrably, editors of “Sumud: A New Palestinian Reader,” talk about culture as a vital form of resistance.

“It’s a wound. Palestine is a wound that doesn’t go away because it’s ignored.”

Where there is oppression, there is resistance. Even when it seems invisible to outsiders, it can always be found in the art and culture of the oppressed.

Malu Halasa and Jordan Elgrably, of the Markaz Review, talk to Steve about Sumud: A New Palestinian Reader, an anthology of essays, poetry, fiction, memoirs, and art.

Sumud is translated to mean ‘steadfastness’ or ‘standing fast.’ Recounting the work of author and human rights lawyer Raja Sheheda, Malu adds:

“Sumud is practiced by every man, woman and child in Palestine, struggling on his or her own to learn to cope with and resist the pressures of living as a member of a conquered people. Sumud is watching your home turned into a prison … It is developing from an all-encompassing form of life into a form of resistance that unites the Palestinians living under Israeli occupation.”

Malu and Jordan highlight the ongoing violence and erasure faced by Palestinians, particularly in Gaza, where artistic expression becomes a vital form of resistance against dehumanization. The Israelis are intentional in their attempt to erase the art, culture, and memories of Palestine. Like the destruction of hospitals, schools, and arable land, it is intrinsic to the genocide.

The conversation also touches on the implications of US support for Israel. Gaza has become an international display of arms and weaponized AI, serving the military industrial complex and global perpetrators of the endless war.

Malu Halasa, Literary Editor at The Markaz Review, is a Jordanian Filipina American writer and editor. Her latest edited anthology is Woman Life Freedom: Voices and Art From the Women’s Protests in Iran (Saqi Books, 2023) has been shortlisted for the 2024 Bread & Roses Prize for Radical Publishing.. Previous co-edited anthologies include: Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline (Saqi Books, 2014) among others. She has written for The Guardian, Financial Times and Times Literary Supplement. Her debut novel, Mother of All Pigs (Unnamed Press, 2017), was described as: “a microcosmic portrait of … a patriarchal order in slow-motion decline” by the New York Times. Halasa has been writing about Palestine for the past thirty years.

Jordan Elgrably is a Franco-American and Moroccan writer and translator, whose stories and creative nonfiction have appeared in numerous anthologies and reviews, including Apulée, Salmagundi, and the Paris Review. Editor-in-chief and founder of The Markaz Review, he is the cofounder and former director of the Levantine Cultural Center/The Markaz in Los Angeles (2001–2020), and producer of the stand-up comedy show “The Sultans of Satire” (2005–2017) and hundreds of other public programs. Most recently he is the editor of Stories from the Center of the World: New Middle East Fiction (City Lights 2024). He is based in Montpellier, France and California.

Steve Grumbine

All right, folks, this is Steve with Macro N Cheese. Folks, I have covered Gaza in many different ways over the last year.

It has been probably the single most gut wrenching subject that our podcast has covered.

Our organization has given voice to many different people to try to bring about a full contextual understanding not only of the brutality that is going on in Gaza, but also the humanity and the survival instincts and the strength of the people and the willingness to fight and to survive. And today’s interview is going to be building on that, and I’m really excited. This is a little different.

The book that we’re going to be covering today is called Sumud: A New Palestinian Reader by Malu Halasa and Jordan Elgrably.

And one of the things that I am most keen about in this is just that we are looking at this from a poetic standpoint, from an art standpoint, from the voices of the oppressed, from those who are surviving in very grim times and that refused to be washed away, that refused to be erased.

And that erasure is, quite frankly, part of the Israeli IDF [Israeli Defense Force], hasbara, you name it, it’s part of their entire approach to dehumanizing and delegitimizing the people of Palestine. So without further ado, I’d like to bring on my guests Malu Halasa and, as I stated previously, Jordan Elgrably.

And let me just introduce you individually one person at a time.

Malu is a literary editor at the Markaz Review, is a Jordanian Filipina American writer and editor, and her latest edited anthology is Woman Life, Freedom Voices and Art from the Women’s Protests in Iran, Saki Books, 2023.

And the other writer is Jordan Elgrably, who is a Franco American and Moroccan writer and translator whose stories and creative nonfiction have appeared in numerous anthologies and reviews. With that, let’s go ahead and get started. So you both, thank you for joining me.

First of all, I really appreciate you taking the time.

Jordan Elgrably

Oh, it’s a pleasure.

Malu Halasa

Thanks for having us.

Steve Grumbine

Absolutely.

This book’s title, I’m not going to lie to you, I’ve never heard the word sumud and I didn’t know what a reader was originally, but offline you told me. I think our audience would love to hear it.

So your new book, Sumud: A Palestinian Reader, brings together essays, fiction, poetry and art, primarily by Palestinian writers. What does sumud mean and why’d you choose it?”

Malu Halasa

Well, sumud has been often translated as “steadfastness” or “standing fast.” But sumud has been an ethos that the Palestinians have really developed and lived over the years.

The Palestinian author and human rights lawyer Raja Sheheda has written from Ramallah that sumud is practiced by every man, woman and child in Palestine, struggling on his or her own to learn to cope with and resist the pressures of living as a member of a conquered people. Sumud is watching your home turned into a prison.

You choose to stay in that prison because it is your home and because you fear that if you leave, your jailer will not allow you to return. It is developing from an all encompassing form of life into a form of resistance that unites the Palestinians living under Israeli occupation.

Jordan Elgrably

I’ve been hearing the word sumud for such a long time. Palestinians have been living under military occupation. They’ve endured dispossession of their homes. What now

numerous human rights organizations, including B’Tsalem, which is an Israeli human rights organization, call Apartheid. And sumud just is how they refer to the fact that they never give up.

Steve Grumbine

Love it. I love it. And so obviously this is a reader. A reader basically is a collection of disparate writings, et cetera.

Can you elaborate more on that, Malu?

Malu Halasa

Well, it is a collection of disparate writings on a topic. And I like to think of a reader as, It’s almost like surround sound, is that you get an array of voices that really shows the complexity of an issue.

And so it’s not that you’re just seeing Palestinian culture or resistance through the prism of politics all the time, is that you’re actually getting individual voices kind of telling the reader what they’re about, what their great concerns are and their aspirations. So readers were quite popular. I think the word is coming back into vogue now.

Especially issues of the Middle East are so complex that you don’t just want one source, you want many.

Steve Grumbine

In what way are you guys connected to the struggle of Gaza? Obviously, we are all impacted by this in one way, shape or form. But you took the extra step of actually putting things together.

I mean, what was your impetus for this? What was your motivation?

Jordan Elgrably

Well, on my side, I’ve always felt like an honorary Palestinian because I agree with Nelson Mandela that until the Palestinians are free, none of us are. And so I look upon the Palestinians as a people that sort of willy nilly, they didn’t invite it, but they became colonized.

And Israel is really a settler-colonial project, although a lot of Jews would resent and disagree with that because of the historic connection that the ancient Hebrews have to that land.

But in the Markaz Review, where most of this material appeared, we’ve always been paying attention to the struggles of Palestinians, Lebanese, Syrians, the Arab uprising, which in Arabic we called Farah, but you called it the Arab Spring. And so the purpose of the Markaz Review is to give voice to the people from the region.

The Palestinians have always been resisting their military occupation. And Gaza is the first place where that happens because it’s actually been under siege for 17 years.

You know, they closed the borders, they closed access to international waters and so forth.

Malu Halasa

I think that my connection to Palestine is that, well, my father’s Jordanian, my mother’s Filipino, but the Jordanians are very close to the Palestinians. And we have relatives in the West Bank. A cousin of mine, through marriage, she hijacked a plane. She was part of the Sabena hijacking in 1970.

But on a very personal note, I can remember during the 1967 war, my father and uncles outside our house talking in the yard. They kept their voices very quiet because they were Arabs and it was at war.

And ’67 was a time when Israel’s success in the region gave them a real ascendancy in American politics. And so Palestine has always been at the heart of our family discussions. It’s a wound. Palestine is a wound that doesn’t go away because it’s ignored.

And the people live so terribly under occupation for so long. And there is a kind of world indifference towards that, that Arab families feel very upset about. And they think about it a lot and talk about it.

Jordan Elgrably

,And don’t forget that the Israeli propaganda, the Hasbara, has long said that there is no such thing as the Palestinian people. That was Golda Meir who said that years and years ago. That idea has been implanted in the American media.

It’s been repeated often enough that there are people who repeat that without really understanding what they’re saying.

Steve Grumbine

Yeah, Pavlovian, almost.

Malu Halasa

I think also Middle Eastern families in America, they don’t see themselves represented, whether they’re Palestinian, Jordanian, Syrian, they don’t see themselves represented in American culture. So they’re always seen as other or outside. And I think that Palestinians and Palestinian culture even more so.

Steve Grumbine

Clearly one of the, I believe, the primary angles of the IDF and Benjamin Netanyahu and the other right wing lunatics that have really just committed, let’s just call it what it is, a genocide.

I know part of what they want to do is literally erase the Palestinians from existence so that there’s not even a scrap of paper that says their names.

I mean, they targeted the hospitals, they targeted the records places so that people’s births are erased, people’s family line erased, records of everything about their existence has literally been erased and turned to rubble. And it feels like maybe what you guys did was give voice so that they’re not erased.

I mean, can you tell me a little bit about what that erasure looks like from the viewpoint of some of the writers that came through? I mean, what are we talking about here? Because from the outside looking in, obviously it’s horrible.

But what does that look like from the other direction, from the other dialectical perspective?

Jordan Elgrably

Let me jump in for a second, Steve. You know, this is not a new thing. It didn’t start with Gaza. Fifty years ago, the Israelis assassinated a writer named Ghassan Kanafani in Beirut.

Actually, it was in 1972. There may be more than 50 years, but in the 80s, they stole the Palestinian film archives.

And there are many, many examples of how they have tried to erase Palestinian culture. I mean, in 1948, when they flattened several hundred Palestinian towns and villages, they tried to erase that history. You know, they paved over it.

So Palestine is like a palimpsest. On the surface there’s one thing, and beneath it is all the history that’s being paved over.

But you know, in this latest iteration, there are many writers and journalists and poets who’ve been killed. And you’re right, they would like to erase those voices if they can.

Malu Halasa

And I think that’s why culture is so important to the Palestinian people. Literature, memoir, poetry, art is so important because in each cultural expression they are saying, we’re here.

One of the things that the book looks at is how art has been attacked really by the Israelis. You know, there are like four founders of the Palestinian modern art movement and they started in the 60s and 70s.

And at that time, the Palestinian flag, it was illegal to show the flag. It was illegal to show the colors of the flag. They didn’t have galleries, there were no art schools in the occupied territories.

So people were doing galleries and shows, exhibitions, in schools and in church halls and, you know, any sort of public buildings. And the Israelis, the IDF would come and they would arrest people if they were showing the flag.

So emblems of nationhood, emblems of Palestinian aspiration on very basic levels were taboo or censored.

And the one thing that the Israelis have been very good at and that Jordan writes about in his essay for Sumud is that the Israelis have always killed moderate voices of Palestinians, you know, Palestinian writers.

I mean, in Gaza, if you look at all the institutions, the universities and schools that have been destroyed, it shows that culture is dangerous to them and that anything that gives a platform for Palestinian voices or Palestinian aspiration or Palestinian culture is something that they are definitely against, that they don’t want. So it is a mighty erasure.

Steve Grumbine

It’s very challenging for me to understand the modus operandi.

I mean, I get a lot of the struggles in the Middle East, but I don’t, for the life of me cannot process why Israel would want to literally erase them. I mean, it’s not just a genocide, it’s literally their entire existence. Jordan, can you elaborate on that?

Jordan Elgrably

Well, I mean, in the case of Gaza, they didn’t allow any foreign press in, and the intention was to not let the news get out. But they’ve completely failed in that, obviously, because, you know, they couldn’t completely cut off the Internet or kill everybody.

All citizen journalists and the Al Jazeera reporters, they killed over 150 of them, of Palestinian reporters, and they killed poets and writers and, you know, intellectuals and professors and so forth. But really the attempt was to limit the world’s information flow. They’ve had a history of actually killing writers.

The essay that Malu referred to, that’s in Sumud that I did is called “They Kill Writers, Don’t They?” And I trace some of the history of other regimes that do that.

And then I go into detail about, you know, know, a number of the different writers that Israel has killed. And why do they do that? I think they feel a sense of impunity, that they can get away with it.

Don’t forget that in 2022, a Palestinian American, Al Jazeera reporter Shireen Abu Raha was killed in Jenin.

And it’s been proven by forensic architecture and other investigations, including the New York Times and the Washington Post, that, you know, the journalists were not near any Palestinian militants and that she was basically assassinated by an Israeli sniper. And the Department of Justice said they were going to investigate it.

The FBI, you know, made some noise, but they ended up saying, well, the Israelis are investigating this. And Israel ended up saying it was an accident and we don’t know who the shooter was.

But, you know, it’s clear that she was taken out because she was the most popular reporter from Al Jazeera on the occupied territories. And so no one has to answer for that murder. And recently there was a Turkish American activist who was killed in the West Bank just a few months ago.

No one’s going to answer for that either. So I think Israel, Israeli officials and the army feel that they can pretty much kill anyone and get away with it.

Steve Grumbine

It’s absolutely insane. I’m stricken by images of Sinwar throwing a stick at a drone going back a few months ago, and just the sheer, you know, fight to the end.

It seems like this was not somebody who was trying to erase Israel. This was somebody who was trying to defend Palestine, defend Gaza, to stand with the people.

I guess when you think about cultural resistance and you think about real resistance, that’s saying, you know, one man’s terrorist, another man’s freedom fighter. I don’t think we give people enough credit.

These people are fighting for their own existence, for their very survival, and yet somehow or another that framing of “they’re terrorists” continues to stick.

Can you help me understand that kind of mental warfare that they’re doing on the world, the propaganda of not giving these people combatants, you know, that they’re fighting for their own survival? Why do you suppose that is?

Malu Halasa

Because they’re being bombed all the time, wherever they turn. There’s no safe haven for them, you know. Why the Israelis are doing that? Only the Israelis know. And I myself am baffled by it, you know. Well, we know what the Israelis want. They want land. And that’s what they’ve been after for quite a while. And it shows with the bombing of the borders of Syria and leaving troops there.

There’s a very interesting map maker, Dr. Abu Sitta, whose maps show exactly how even with armistice lands, like for example, in the ’67 War, that the Israelis took more of Gaza and then they put the kibbutzim along that wall. So the people who were imprisoned in Gaza were actually looking over at the wall. That’s where their families were from.

And they are corralled there in what is an open air prison. And there’s so much space and land on the other side of the wall.

So I’m not really sure exactly why the Israelis are doing that or what they want, except on a very basic level, they want to control more of the land and they do want to depopulate it.

Steve Grumbine

My question regarding Sinwar was to bring about a form of resistance. But you all talk about the cultural resistance and why do you think that that is so reviled, if you will.

Why do you think the cultural resistance is seen as such a scary, frightening thing?

Malu Halasa

Jordan, what do you think?

Jordan Elgrably

Well, I mean, you can look at the history of dictators going back to Stalin. I mean, well before him, who believed that writers were dangerous.

Even the Turkish leader [Recep Tayyip] Erdogan has said as such, you know, writers are dangerous, words are dangerous, so they don’t mess around. I can read from that, if you like.

Steve Grumbine

Oh, absolutely.

Jordan Elgrably

Just a little bit of this essay, “They Kill Writers, Don’t They?”

So murder is the ultimate form of censorship.

Yet when a regime kills a writer, a poet, or a journalist, the writer’s words live on.

Spain’s dictator Francisco Franco, who ruled the country for four decades, pursued a brutal policy of repression against Spanish poets and writers, evidenced by the fascist murder of poet Federico Garcia Lorca.

Franco feared the threat that writers posed. Little known is the fact that he had been a journalist who wrote 91 articles under three pseudonyms for the right wing rag, Ariba.

In Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini and Mohammed Hatami and their regime’s supporters were responsible for a spate of murders from 1988 to 1998 that included dozens of writers, poets, translators and intellectuals. Under Stalin, many writers were imprisoned, sent to Siberian work camps, or driven to suicide.

In recounting Stalin’s story, the historian Simon Sebag Montefiore wrote, literature mattered greatly to Stalin. He may have demanded engineers of the human soul, but he was himself far from the oafish philistine which his manners would suggest.

He not only admired and appreciated great literature, he discerned the difference between hackery and genius, unquote. Nonetheless, one of the writers, Stalin silence was Isaac Babel, who had published stories critical of the Russian Army.

Babel was accused of, quote, being a member of a terrorist conspiracy and cut down by a firing squad. Before they took him out into the yard. He denied all the accusations against him, his last words being, quote, “I am asking for one thing only. Let me finish my work.” Unquote.

Decades later, after the fall of the Soviet Union, the archives at the KGB were open and Babel was exonerated. Today, Israel declares itself, quote, the only democracy in the Middle East and insists it follows international law.

Yet it offers no explanation or legal justification for having murdered more writers than any other country in the world.

Now I remember feeling shock and disbelief when I first learned that writers were were killed for their books and their ideas, for their poems and short stories. Were their words so dangerous as to merit their execution? Could writing really be a lethal profession.

And I’m going to stop there. But the essay goes on and it talks about a number of the different Arab and Muslim writers who’ve been killed by different regimes and so forth.

Steve Grumbine

It’s absolutely terrifying when you think about the writers being eliminated. This obviously goes to journalists, as you’ve already stated. What do you suppose is the US’s –

If you don’t know the answer to this, it’s fine, we can scratch this – but what do you suppose is the US’s modus operandi for supporting this? For literally carrying the lie? Is it AIPAC [American Israel Public Affairs Committee]?

Is it some sort of geopolitical angle? Is it, you know, the right wing Christian fundamentalists thinking that they’re saving Israel?

What do you think is the modus operandi of the US for supporting this?

Jordan Elgrably

Now, officially, the US supports human rights, international human rights, subscribes to the Geneva Conventions, officially. But the US has allowed Israel to pretty much run rampant and do almost everything that it wants.

For me, the key to understanding this goes back to June 1967, when Israel bombed a USS intelligence ship, the destroyer USS Liberty, and Lyndon Johnson shoved it under the rug. And it’s still something that most people are not aware of. And Israel got away with that.

And I feel like since they got away with killing over 30 American sailors and almost destroying, almost sinking the ship, and they did it for reasons that, you know, are too complicated to get into right now, but it was an act of war and it was fine. They got away with it. So, you know, they can kill journalists and get away with that. Why not?

Malu Halasa

Yeah, but I also think that – you’re right, it’s all the reasons that you stated, Steve – but also I think that what we’re missing and what we don’t know are the military ties between Israel and the United States.

And also remember, just as Syria was a way for Russia to sharpen its abilities at war, the Israelis are trying out a lot of new technology, AI [artificial intelligence] being one, to identify allegedly terrorists. And we know that AI hallucinates and makes a lot of mistakes, so it can easily mistake a world food aid worker as a terrorist.

So I think that there is a tie between the two militaries that’s not really being talked about. But because we had Jordan read from his essay about writers who have been killed or how writers are targeted by authoritarian regimes.

I think we should bring it back to Palestinian poetry because I think that there have always been great poets and that it’s not that they’re undergoing a renaissance, but that we’re finding more and more. We’re hearing their voices more. And I’d like to read a little bit from the introduction for Sumud, starting with Musab Abu Toha.

He is one of eight poets featured in our anthology. Poetry has always held a special place in Palestinian literature and the Arab psyche.

It has also been one of the best tools in the Palestinian arsenal to counter Israeli oppression. This was acknowledged by Israeli General Moshe Dayan, who once likened reading one of Fadwa Tuqan’s poems to facing 20 enemy commandos.

The anthology closes with Hala Alyan‘s poem Habibti Ghazal, which is part love swoon, part warning. Alyan is an award winning poet, author and clinical psychologist. The title of her 2024 opinion piece for the Guardian I Am not There, I Am Not Here.

A Palestinian American poet bearing witness to atrocity, references to Bach, a counterpoint, an elegy for the late Edward Said, written by great Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. In this article, Alyan explores an essential aspect of contemporary Palestinian life and she’ll bring us back to the idea of sumud.

“Sumud has become a multifaceted cultural concept among Palestinians,” she has written. To its usual meaning of steadfastness, she adds that the word in Arabic is “a derivative of arranging or saving up, even adorning. It implies composure braided with rootedness, a posture that might bend but will not break.”

And I think that that’s the power of Palestinian resistance and culture. It’s that no matter how difficult it gets, even with all of the modern technology, the best AI against them that people are moving from, you know, allegedly what should be a safe haven and they’re bombed to another place is that they’re still resilient, they’re still there.

Intermission

You are listening to Macro N Cheese, a podcast by Real Progressives. We are a 501c3 nonprofit organization. All donations are tax deductible.

Please consider becoming a monthly donor on Patreon, Substack or our website realprogressives.org. Now back to the podcast.

Steve Grumbine

I remember distinctly seeing the drones run by AI and they would make sounds to bring the kids out and then they kill them. And it’s like, am I really? Is this not a horror movie? Like literal horror movie? Not a war movie. A war movie. It’s like, oh, it’s gross, it hurts, it’s painful, blah blah blah. But it feels like war. This doesn’t feel like war. This feels like cold blooded murder of children.

Seeing the AI deployed like this and knowing that it’s hand in glove with the United States is deeply, deeply troubling.

Can you talk to me just a little bit about, you know, maybe some of the specific writings outside or including the poetry that maybe you found to be the most inspirational.

Malu Halasa

I found this short story inspirational, but also what I found… It’s called Application 39. It’s by Ahmed Massoud.

And people don’t associate humor, even black humor, with Palestine, but this is about a sort of like a hacker’s bid to get Gaza City to apply for the Olympics and win the bid for the Olympics.

But the story itself, it’s set in a dystopian future and there are drones that come down and look at these hackers and you know, they have to state who they are, but one of the hackers has a computer hidden and he’s able to disable the drone.

You know, recently I heard a story of an aid worker. A drone flew right – you know, an Israeli drone, IDF drone – flew right in front of him, asked him to identify himself, asked him to show what was in the, the trunk of the car, asked what various things were. And because he was able to answer in a way that, you know, satisfied the people who were controlling the drone, he was not killed on the spot.

So, you know, even in Palestinian science fiction, what their worst case scenario that they’re writing about, thinking about – the future – is happening right now.

Jordan Elgrably

Absolutely, yeah. You know, there’s another book that deals with this. It’s called Palestine Plus 100, meaning 100 years.

And there’s a lot of futuristic writing in that book. But I think the future is here right now. What’s happening in Gaza with all of these drones? And they’ve been there for years.

This goes back to 2008, 2009, and Gazans have become used to it. They’ve become much more deadly in the last two attacks in 2014 and now.

But can you imagine that the drones are not going to be coming to us in other countries? I think we’re just around the corner from that kind of control.

Steve Grumbine

Yeah. You know, I think to myself, and maybe this is slightly outside of topic, but I think it ties directly to it.

But I know as an American living in the continental US that even though my heart feels tremendous fear and both sorrow, there’s nothing that can compare to physically being there.

So in the us I think people are oftentimes, you know, walled off from the reality of even seeing the TikTok videos and seeing all the other writings and pleadings and so forth from that. It still is surreal. But to your point, Jordan, it’s happening now, it’s not happening in some far off future, it’s happening now.

And those technologies are being rolled out in various places throughout the US even right now.

I mean, you look at Cop City that is being developed in the South, you look at some of what’s going on, even, even in the wildfires in California right now, we see prisoners being put out to the front lines to put out these fires.

And once again, all these ideals that we have as quote, unquote, the theoretical American dream, which is largely an American nightmare for a great many people, it still pales in comparison to what is happening now. So I don’t think people realize that the moment is now. It’s not in 10 years, it’s not when it’s convenient. It’s happening right now.

And how might you present that to our listeners, you know, from your vantage point: the nowness of it all?

Jordan Elgrably

Well, we know that drones are being used by the US military in many countries, a lot of Muslim countries, they fly drones over and people are being killed. The collateral damage in Yemen and in Syria and Iraq and so forth. So our taxpayer dollars are paying for people who are being killed. We don’t even know their names.

Malu Halasa

You know, getting back to how we can think about the nowness of this violence, you know, the New York Times has been showing aerial views of parts of LA that have been destroyed by fire. And when I look at that, I also think of the views I’ve seen of Syria that were destroyed in the Russian bombing of for example, Halab, or Allepo

And that also makes me think of the images that I’ve seen of Gaza, of street views that have been completely bombed. And I think that the nowness of it… Okay, what’s happening in LA, of course is wildfires, and it’s nature, but it’s man made. It’s the result of what’s been going on with fossil fuels. It’s the heating up of our environment. What happened in Syria was happening in Gaza. It’s man made.

And I think that for me that’s the nowness of it is that these places, you know, especially for Americans, they thought that the west coast was secure, but it’s not anymore. And there are places in the world outside of America that haven’t been secure for a long time. I don’t know if that will make Americans think more.

I, I hope it will. But our world is becoming smaller now. We’re being connected by tragedy.

Jordan Elgrably

And something else that I want to remember also, is that, okay, when I say the word Hiroshima, listeners, in their mind, they go back to, oh, this is history, you know, World War II, 1945. But Israel has dropped so many bombs on Gaza that it’s the equivalent of five Hiroshimas.

Steve Grumbine

Wow.

Jordan Elgrably

Imagine that. And not only that, but the pollution. I mean, you know, Gaza was actually fairly fertile. And then there were farmers.

Well, I don’t know if anything is going to grow in Gaza for a generation. So, you know, they’ve committed genocide, but they’ve committed – what’s the word – ecocide.

They’ve also destroyed the universities, all of the universities. A lot of the schools are destroyed.

Malu Halasa

Scholasticide.

Jordan Elgrably

Scholasticide. So, I mean, there’s so many different ways that Gaza is being decimated. And I think that we’re going to see this happening in other places.

The fact that Israel’s been able to so far get away with all of this.

Again, they’re testing their technology on the Palestinians, but other countries are seeing what’s happening and they’re seeing what they are getting away with. And this means that the entire world is less and less safe.

Malu Halasa

And it also means that this technology will be sold to authoritarian regimes. Gaza is like a showcase for this stuff, you know.

Steve Grumbine

Wow.

Malu Halasa

And it’s not going to stay in Gaza. That’s the message, I think, that is missing from everything we’re hearing.

You know, the people on the left who really care, they have to understand that’s what’s going on.

Steve Grumbine

Yeah. You know, as a podcast, we mostly focus on macroeconomics, interestingly enough.

And one of the most horrible lies that’s ever been told is that it’s our tax dollars that are funding all these things.

This goes back to Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, when Thatcher famously said, there is no such thing as public money, there’s only taxpayer dollars. And ever since then, we have thought of ourselves as like a household budget piggy bank, when in reality, it’s much more nefarious than that.

Our government creates money every time it spends. It doesn’t wait on your tax dollar. Your tax dollars are shredded.

And so what ends up happening is they have an unlimited kitty to fund warfare around the world while simultaneously telling everyone, we can’t afford to take care of climate crisis, we can’t afford to give you Medicare for our healthcare, we can’t afford to get rid of student debt and make education a right, we can’t make housing a right. We’ve got more homeless people than you will ever know.

And the lie is so pernicious, and it’s said so frequently and we believe it so earnestly that they allow us to fight within ourselves for an austerity narrative. Yeah, based on something that is not real.

The coupon issuer being the federal government and its fiat currency spends this money into it, literally spends it into existence. So everything you see happening over there, every nickel that is given to Israel is given to them and they could give them even more.

You notice they don’t raise taxes to pay for all these billions are given to Ukraine or billions are given to Israel. They never raise taxes for it. Why not?

It’s because taxation stopped funding federal government many, many, many moons ago. I mean, 1946, I think the guy’s name was Beardsley Ruml and he said taxes for revenue are obsolete. He was a Fed chair at the time.

And we’ve known this for a long time.

But they obscure it because they want austerity for the people, while simultaneously that open air experiment in the open air prison of Gaza that they’re using as a showcase for the military industrial complex to sell its wares and to enable capital to run rampant around the world. I mean, the level of dystopia only goes deeper the further you get into understanding the role of the IMF [International Monetary Fund] oppressing the global south.

And Gaza is a large part of that. Talking to many good African economists and understanding the way that the US has a forked tongue talks both,

We don’t have money, where are we going to get money? It’s irresponsible.

We’ll check out a credit card for the People’s Republic of China, blah blah blah, like Obama said, while simultaneously, they never even flinched. They don’t even have to, oh my goodness, what bed are we going to dig under to find the money to give Israel? It’s never a problem.

It’s only a problem when it comes to something productive, something that would help, something that is for the people. Because as long as we are desperate, we won’t fight back. We can’t fight back.

We’re under a lie, a narrative that keeps us constantly striving, and lo and behold, now we’ve got a genocide in front of us. And you watch the kids, the children at the universities getting beaten down by police, et cetera.

So it’s meant to, I believe, make us feel completely feckless, completely incapable of change, completely incapable of taking on this Leviathan.

I think that’s what’s so fascinating about this reader that you guys have put out is that instead of inspiring doom’s feeling and complete impossibility of it all, I believe its target is to bring about the hope, this is a story of hope.

Malu Halasa

Yeah, it’s sumud. Because facing this onslaught, everything that you’ve described is just, I mean, what are we going to do?

And the only thing we can do is to hold fast and create art and help other people’s expression. Make platforms. And all of this really does remind me of something that we have in the introduction. I don’t know if you… would you mind if I read another short passage?

Steve Grumbine

I got a 15 page intro that I read earlier that was amazing. I would love for you to read from it. Yes, please.

Malu Halasa

Well, this was told to me by a Palestinian family, and when they told it to me, Jordan and I were writing the intro and I had to put this story in because I thought this encapsulates not just sumud, not just Palestinian resistance, but the human condition and the human spirit on many levels. Not just the people who are victims, but also the people who are oppressors. And I’ll read it now.

“During the war on Gaza, there have been scores of trophy videos posted on the Internet by Israeli soldiers in the Strip. One that appeared on TikTok shows a devastated home.

The Palestinian family who owned the property discovered it by chance, having been forced out of the same house months earlier, and sent the short, disturbing film to relatives and friends. In it, an IDF soldier films his unit.

Helmeted and armed combatants yell to each other as they make their way through the debris on the stairs and utterly trashed rooms. Sunlight streams in through the windows.

Every now and then, the soldier points the camera downward and a family memento, perhaps a framed picture, can be glimpsed among the smashed furniture and the detritus strewn across the floor. From the layout of the house and the curved metal banister on the stairwell, it was obviously once a gracious family home.

It’s unclear why the film was uploaded in the first place. By the time it arrived in one of our WhatsApp group chats, a comment in Hebrew had been posted on the video.

It read: ‘In the midst of battle, I see a mirror.’ These words seem less triumphant and more reflective. One could even suggest that the person who made the comment feels ashamed.

In this time of brutal, unassailable war, what is the power of culture? It not only reveals who we are to others, but in many ways demonstrates the essentialness of who we are to ourselves.

The elderly Palestinians who own this house, who brought up their many children and their grandchildren in it, they were also shown in the video. Afterwards, they said to themselves, we can fix this. We can do this. All the bombing and the deaths of family members had not broken them.

They still had the expectation of returning home. There can be no better embodiment of sumud.”

Steve Grumbine

Wow, that’s fantastic. One thing as we come toward the end of our conversation here. You know, obviously this has been in the news now since the October 7th [2023].

It’s been going on now for over a year. Obviously it’s got a much, much, much longer history and I appreciate you taking it back to the 40s as well. But it goes back even further.

I’m curious, in terms of right now, what do you think the world’s take on Gaza is? How do you think this plight of the Gazan people has played out for most of the world? For popular opinion, etc. What do you think has changed?

Do you think people are more aware? Do you think they’re more sympathetic? Do you think this has hurt Israel?

Jordan Elgrably

I think they are more aware. And I think that the, the movement has grown in strength. We’ve seen massive demonstrations over and over in capitals like London and New York.

And we’ve seen groups of progressive Jews occupy Grand Central Station, the Senate Capitol building. The French President Emmanuel Macron tried to ban pro Palestinian demonstrations. This completely backfired. And the Place de la Plubique in Paris was packed on multiple occasions. Oh, I think that this whole movement has gained a ton of momentum. It reminds me of the anti-apartheid movement of the 80s.

People don’t remember that it took about four years toward the end for the regime to finally collapse and give in to the sanctions that were happening. And so I think we’re at a point where for the next few years Israel is going to try and do everything it can to resist.

But there are lots of American universities, for example, who have now disinvested from Israel. We’re not hearing about it that much right now because there’s a lot of anti Palestinian speech in the government and media.

But students and progressive activist groups have made a difference in the US. So I think that’s probably a trend that we’re going to see continuing in other parts of the world.

Malu Halasa

Also, I want to tell you about a group called Airdrop [Airwars]

Airdrop [Airwars] is a group of activists who, using forensic techniques, looking at film footage that the IDF is quite proud of and posting on the Internet saying ‘this is a precision bombing in Gaza.’ What Airdrop does is that they take a 360 degree view of that bombing with witnesses on the ground who have been filming it, and they find out who was inside the building when that bomb went off. Is this really a precision drop?

And they’re able to verify in one of their investigations that it was a teacher inside the building and that it isn’t a precision drop. And what they’re doing is that they are collecting this evidence.

And I heard Emily Tripp, she’s one of the main people there, and she said that you have to remember that war crimes, it takes a long time to prosecute people with war crimes. But what Airdrop is doing is that they’re collecting and collating the evidence. And I think that what’s happened, it’s true.

I never thought in my lifetime I would see the sea change against Israel.

But what’s also happening is that you have groups like Airdrop, like Forensic Architecture, that are really gathering information, and this information will eventually be used in war crimes tribunals and trials.

So I think that that’s also something that’s important to understand what’s going on, that that’s one of the important things: that activists, people on the ground, are actually gathering information and taking steps themselves.

Steve Grumbine

Wow. First of all, I want to thank you for joining me today.

But before we close out, I’d like to give each one of you a chance to put an exclamation point on this. I’ll start with you, Jordan, and we’ll circle back to Malu for the final word. Give us your parting thoughts there.

What do you think is the most important thing that we did or didn’t capture in this call?

Jordan Elgrably

Well, I think we definitely should remember that this is a book largely by Palestinians, about Palestinian life, and that it’s very important for everyone who is interested in strengthening humanity, period, that we should support literature and art and we should support freedom of expression. And, you know, Sumud: A New Palestinian Reader, really is a celebration of the freedom of expression.

Expression, which is the fundamental human right that Markaz review supports. Great.

Steve Grumbine

And you, Malu?

Malu Halasa

Well, I think what’s important is that books, movies, music, all of this is a platform for individual voices, for individual voices to express who they are, but also to celebrate the human condition. And I think that Sumud does that. Because for so long, the Palestinians have been invisible and they’ve been erased, that to see their culture front and center is incredibly powerful. And I think that’s one thing that I wanted the book to do.

I wanted it to be a platform for these voices and for these ideas, because these ideas are not ideas for the Palestinians alone. These ideas are ideas for all of us.

Steve Grumbine

I love it. I love it. You guys were great. I really appreciate you all joining me today. I’m sure there’s much more that we could have gone into.

But, folks, I hope you’ll go ahead and get the book. Sumud: A New Palestinian Reader by Malu Halasa and Jordan Elgrably. Where can we find more of both of your work?

I know, obviously at the Markaz Review, but where else?

Malu Halasa

Oh, I’ve just written a story about Felice Rosser and Faith NYC and racism and misogyny and rock, for Index on Censorship.

Steve Grumbine

Oh, wow. Okay. And how about you, Jordan?

Jordan Elgrably

Well, I have a book that came out recently in which actually Malu and I both have short stories. It’s a collection of short stories from City Lights Publishers in San Francisco.

It’s called Stories From The Center of the World: New Middle East Fiction. And I think that’s pretty much available everywhere.

So if you like short fiction and you’re interested in Palestinian writers and other writers from that part of the world, it’s a pretty good book.

Malu Halasa

And also, everyone, join us at the Markaz Review. We just did a double issue on genre fiction. You know, horror, sci fi, romance, detective fiction.

It’s kind of amazing, the new writing that’s coming out of the Middle East. Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, North Africa.

There is a lot of very good writing that’s happening, and you’re not going to read these stories in the mainstream press, so come on out to the periphery.

Jordan Elgrably

Right.

And also, thanks for mentioning that if people go to themarkaz.org and click on events, you can see where we’re going to be on tour on the east coast presenting this book. We’ll be in D.C. New York, and Boston, Harvard, at the end of January and early in February.

Steve Grumbine

That’s fantastic.

Malu Halasa

And one last thing, we’re always looking for new and interesting writers.

Steve Grumbine

Ah, okay. Opportunity. There you go. All right. Well, folks, thank you very much for your time. Let me just say, my name’s Steve Grumbine.

I am the host of the podcast Macro N Cheese. And I’m also the founder of Real Progressives, which is the parent company of this podcast. We are a 501c3 nonprofit and we survive on your donations.

So please, if you consider the work we’re doing worth your time, please consider donating to us. You can either find us on Patreon at Real Progressives, or you can go onto our website, realprogressives.org and donate.

Or you can go to our Substack and become a donor as well. And with that, I’d like to thank both of my guests, Malu Halasa and Jordan Elgrably, one more time on behalf of Macro N Cheese myself, Steve Grumbine. We are out of here.

End Credits

Production, transcripts, graphics, sound engineering, extras, and show notes for Macro N Cheese are done by our volunteer team at Real Progressives, serving in solidarity with the working class since 2015.

To become a donor, please go to patreon.com/realprogressives, realprogressives.substack.com or realprogressives.org.

Extras links are added in the transcript.

Related Podcast Episodes

Related Articles

All Frogs Go To Heaven