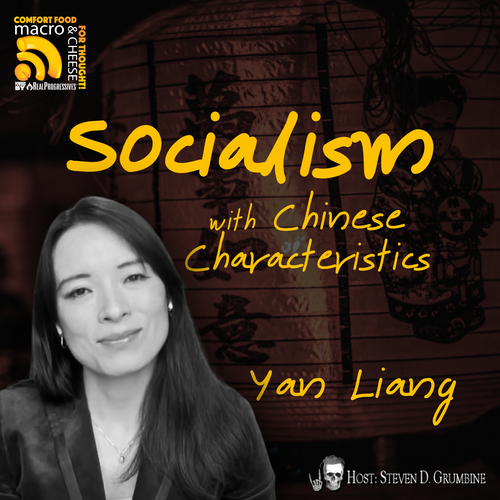

Episode 357 – Socialism with Chinese Characteristics with Yan Liang

FOLLOW THE SHOW

Yan Liang and Steve Grumbine apply the MMT lens to China’s economic strategy, capital controls, and global partnerships. This is crucial for anyone serious about anti-imperialism and monetary sovereignty.

In today’s world, anyone serious about anti-imperialism, global development, and monetary sovereignty needs to break through the well-funded US propaganda machine and develop a fact-based, nuanced understanding of China.

To this end, Steve asked Yan Liang to come back to the podcast to look at China through the MMT lens, analyzing its economic management, global role, and response to Western villainization. They discuss China’s development ethos and describe China as a state that actively uses its monetary and fiscal sovereignty to guide development towards internal goals (poverty alleviation, technological self-reliance, common prosperity) and external partnership (Win-win cooperation, Belt and Road Initiative).

Illustrating the difference between state steering and the so-called “free market,” the conversation goes into China’s mobilization of real resources through strategic state guidance, like Five-Year Plans and state-owned enterprises in key sectors.

Yan talks about the use of capital controls and a managed exchange rate. She details lessons from 2015 and the application of MMT principles to insulate domestic policy from volatile external forces.

Without romanticizing China, Yan also walks through its real challenges. But from an MMT-aware lens, these are seen as problems of policy design and resource use – issues a sovereign, planning-oriented state can address – rather than proof of an impending collapse.

Yan Liang is Peter C and Bonnie S Kremer Chair Professor of Economics at Willamette University. She is also a Research Associate at the Levy Economics Institute, a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the Global Development Policy Center (Boston University), and a Research Scholar of the Global Institute for Sustainable Prosperity.

Yan specializes in the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), the Political Economy of China, Economic Development, and International Economics. Yan’s current research focuses on China’s development finance and industrial transformation, and China’s role in the global financial architecture.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/yan-liang-1355b91a2/

@YanLian31677392 on X

Steve Grumbine:

Alright, folks, this is Steve with Macro N Cheese. And today’s guest is Yan Liang.

We have had her on quite a few times and she is one of my favorite MMT economists, but she’s also focused heavily on China, and because we’re watching China do amazing things-

Now, I’m not here to tell you China’s perfect, everything has got warts, everything’s got its own shortcomings, I don’t know what they all are, and I’m not here to proclaim them-

but what I am here to do is watch the absolute majesty of production that is going on in China, the real genuine progress that has been achieved for so many people in China.

Now, whether you want to complain and say, “Oh, Steve, that’s not real socialism,” or whatever, that “They’re really capitalist, Steve” and it’s like, well, somebody would come back and say “It’s socialism with Chinese characteristics,” is how they would claim it. And then the flip side is- as an MMT podcast, as an MMT organization- we also understand the way that currency works.

We understand the way that nations that create their own currency, or have their own currency, their own legal unit of account, that they do things in a way that seems mystifying to the average person. And we’ve tried to talk about this through the lens of BRICS, I think we’ve even talked a little bit about it through the lens of what we get wrong when we think of China.

We’ve had several folks come on to discuss this, from Carl Zha to my guy [Vincent] Huang, and we’ve had several other guests that have really, really brought out other aspects of it, but today I really want to focus on the convergence of MMT and socialism with Chinese characteristics. And that will be our discussion point today.

So without further ado, my guest Yan Liang is Peter C. And Bonnie S. Kremer, Chair professor of Economics at Willamette University.

She is also a research associate at Levy Economics Institute, a non-resident senior fellow at Global Development Policy Center, Boston University, and a research scholar for the Global Institute for Sustainable Prosperity where Fadhel Kaboub and Matt Forstater and others you know. Yan specializes in MMT, the political economy of China, economic development and international economics, which fits right into the conversation we have today. Yan, thank you once again. Thank you so much for joining me.

Yan Liang:

Yeah, thank you Steve for having me again. It’s always a pleasure to talk to you and your community.

Steve Grumbine:

I appreciate that so much. This is challenging, right?

I mean, a lot of people, they read the newspaper, they hear our politicians in the US, they heard Joe Biden, they’ve heard Donald Trump… all they do is demonize China, like somehow or another China is coming in and trying to hurt us, they’re our enemy and so forth.

And I didn’t buy it when Biden said it at the State of the Union, I didn’t buy it when Trump started ratcheting up the tariffs, and I still don’t buy it.

And I plan on never buying it until evidence creates some form of fact-based trail that leads me to that, but I don’t see any of those things.

In fact, my own very small, narrow window of view, of a month journey into China back in 2008, 2009, for myself, I got to see firsthand some of the things. And I got to go to Beijing University, I got to talk with various individuals, and different intermediaries and so forth, and I’ve been nothing but impressed. I know that there are problems, but I’m living in a country-

we’re living in a country, you’re living in a country-

that is full of just downright austerity and economic ignorance.

And quite frankly, I don’t think of it as ignorance, I think of it as a weapon, I think of the economic violence being wrought on the citizens of the United States, and really with our imperial strategy, ends up being violence against the rest of the world… to maintain markets, to maintain access to real resources, to open markets for the oligarchy, that Bernie Sanders is claiming to fight right now. All these things, you have to keep them, I think, together, I don’t think you can Balkanize them and cordon them off, and “we’re going to look at this little teeny thing here”, because they all connect. And China is being labeled as an imperialist nation, and I don’t see any of that. I don’t see any of that.

And if it is empire, it’s a very soft empire because it seems to want win-win solutions for people. Help me understand, if you will, kind of what China’s driving ethos is towards its economic development and its approach to international economics.

Yan Liang:

Right… So I think China, to many people, is some sort of a myth. And I think you’re right, I think the mainstream media really doesn’t help to provide the clarity and the facts to allow us to really understand China. Most of the time I think the Western narrative, it demonizes China for all kinds of reasons, out of ignorance, out of a specific political agenda and so on.

There are many people who have never set foot in China, and yet they seem to say, “China is this poor third world country and it’s repressing its people”, and there are a lot of these kind of spews on X.

But then there is also people who understand China’s rise, but they’re really worried about China as a threat, “China’s steals our lunch” and so on and so forth.

And so they demonize China because they want to shift expectations, making China “un-investable”, so it can, in some ways, dampen its economic growth… so I think, you have all these kinds of motivations.

But I think, for me, China is a reality, China is a 1.4 billion people country, and it’s striving to achieve sustainable development, and trying to lift its people out of poverty and provide a certain level of living standards for the people. It is, right now, the second largest economy in the world, and by some standards, it has been the largest economy for a while, if you use a PPP [purchasing power parity] measure, for instance, and it’s undeniably a manufacturing superpower. It is now also really quickly climbing up the value chain, becoming a technological leader. It is also one of the major drivers of the global renewable energy campaign, to achieve accelerated green transition.

But yes, China has very different political, economic, cultural value systems. And so I think with the difference, this is also one of the reasons why there are people who either romanticize China or demonize China.

But I think, as a scholar, and I think, as activists, we really need to understand China as what it is, learning from its strengths, and in a way, avoid some of the mistakes that it has made, in its own, sort of, development past.

And also I think it’s important to really engage with China. Like any other countries, China has its own interests, but China is also trying to gain, you use the word “soft empire,” or it wants to really get the recognition from the global community. And China is also increasingly trying to get into position where it doesn’t always just follow the rules that are being imposed on it, iIt wants to be part of the rule making.

So all of this just to show that China has its own interests, it has its own agenda.

So far, I think what China has done, not only helped to benefit its own people, lifting over 800 million people out of poverty-

I mean, that is really unprecedented accomplishment in human history, so I think we need to acknowledge all of this-

and also understand yet China wants to have a role to play in the global landscape, and so far, I think, again, through BRI [Belt and Road Initiative], through its partnership with other countries and platforms like BRICS, SEO, and with ASEAN countries, and so on and so forth, it seems to be benefiting, by and large, the global community.

And of course there are people who argue China can do more, or China can work on some specific areas, like for example, debt relief for many of the African countries, and again, China has been doing that.

So, I think we need to have a balanced and really fact-based understanding on China, and I think that is to our own benefit. If you really think China is going to collapse tomorrow, you’ll be wrong and surprised again and again when China fights back.

Steve Grumbine:

Yes.

Yan Liang:

When, for example, the United States thinks that they have all the cards, and China goes, “Well, I made those cards.” So I think this is really problematic when we try to downplay, China’s power and the value that China brings to the world economy.

And at the same time, again, I think we should also try to avoid the other extreme, which is to say that whatever China does is correct, and whatever China does, we need to support. I think there is still a lot of agency for the rest of the world.

And also I think for scholars within China to, in a way, sway China’s policy.

I believe China gets the right directions when it comes to sustainable development, common prosperity, and when it comes to the global economy, China’s strive for renewable energies, for technological breakthroughs, I think all of these are the right directions, but still I think we could hold China accountable, and we could see where China’s strengths and weaknesses are, so then we’ll be able to more productively and efficiently engage with China, knowing what China wants, and knowing what China’s trying to achieve, so then, I think, we would be able to engage with China better. So that’s why I think genuine understanding of China is very important.

And you ask some of the drivers, and again, I think China so far has been really trying to better manage its economy, socialist market economy, trying to bring moderately prosperity to its people.

This is their 2035 goal, to achieve the relatively middle high-income level for its citizens, and try to bring the per capita GDP double by 2030, from the 2020 level. And also trying to be more self-reliant on core technologies, and upgrade its traditional sectors, and so on and so forth.

So, a lot of these are internal development driven goals. And then externally, like I said, it wants to, in a way, partner with the Global South countries to develop these kinds of alternative development paths to be more sustainable, more inclusive, and also to really get some kind of say at the international negotiation table, when it comes to trade rules, investment technologies and so on. So I think that is what really drive China’s moves, when it comes to its policies, when it comes to its plannings, and also when it comes to its engagement with the rest of the world, be it with the United States, Europe or Global South countries.

Steve Grumbine:

You know, we see in the United States that there’s absolutely a weird kind of pushback against any kind of interference from government on capital controls, or people act like, “Well if we sell these bonds and stuff like that, then they’re just going to buy up the country”, failing to understand that the United States government could easily pass a law saying ‘no foreign entity can do xyz’, and voila, guess what?… They can’t do it anymore.

China does these things, it protects itself, it protects itself from billionaires, it protects itself from interests that don’t serve China’s interests… It puts China first. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Yan Liang:

Well yeah, I mean, honestly, the United States does have very heavy dose of state intervention, all these ideas about ‘free market’, I think it’s completely a myth. think from [James K] Galbraith, the sort of predator state, or Dean Baker had this nanny state, and I think for MMT, we also really understand the state holds a lot of power, it writes the rules for the market.

So I think for the United States, it’s not that there is no government interventions or management of the economy, but really it’s that they use the kinds of state tools to advance the interests of financial elites and to gain private profits.

It’s whole idea of the US is a socialist economy in the sense it only socializes the costs of doing businesses or making profits, and they privatize all the gains, the profits in that sense.

So I think, yes, the United States actually has all these rules to scrutinize foreign investments within the United States, so at the state level, there are many states that preclude China’s investments in any land ownership.

And we also see, starting early on from the Biden administration, you also see the US basically prohibits China’s investments in tech companies and so on, so forth. And also our investment, there’s also scrutinization where private equities, or some companies, are not allowed to invest in certain sectors in China.

So there are a lot of these rules. It’s not that the US is not doing it, it’s just that they’re doing it not for the interest for the great majority of the people.

They’re really trying to protect certain interests, they’re trying to really privatize the gains and trying to protect their businesses away from China’s competition, again, using all kinds of excuses. It could be ‘this is the CPC’s agenda, trying to take over the economy’ and so on and so forth. I can give you two specific examples, one is very recent, Trump’s administration banned Nvidia to export the H20 chips-

one of the relatively high end, not the highest end GPU chips-

the AI related chips, to China, and claiming this is for national security reasons.

But after certain negotiations from Jensen Huang, and after certain considerations, the Trump administration then decided, “Okay, yes, you can export to China these H20 chips, but you have to give me a 15% cut.” I’m not joking, this is what the US government, this is what Trump’s administration said, “Oh, you can’t sell because it’s national security… Oh, never mind, if you give me 15%, yes, go ahead and sell those H20 chips.”

[Payola, huh?]

Yes, you have to scratch your head, what is going on right now?

So this is one example that you can see the government does interfere, or does, in a way, intervene in the economy, but not for the purpose that you would like it to be.

And the other example is, again, with all these tariffs, back and forth-

and Trump has been doing this now in the most recent days, they started to exempt over 100 food products from tariffs-

Now again, when you think about this, this is quite interesting because the tariffs-

especially all these reciprocal tariffs that Trump imposed-

was largely based on the IEEPA, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, that says all these imports create some kind of national economic emergency, that allowed Trump to impose all these blanket tariffs on other countries. But then you also ask, well all of a sudden, now all these hundred tariffs are gone, so what happened to the national emergency now?

Are these still emergency or not?

So I think what it shows is that this whole idea of national security, or emergencies, that justifies government’s interventions-

and especially I’m talking about the executive branch, because none of these tariffs are approved or sanctioned by the Congress, is Trump is the presidency that impose all these tariffs, right, in the name of emergencies or national security threats.

But then you can see how he easily takes this on or off, right, based on again, various considerations. The most recent one I think, again, is this really outcry of affordability crises.

And don’t forget Trump used to call these the ‘Democratic con jobs’, he does not believe the so-called affordability crises, until, I think, really, the kinds of protests, the kind of outcry is getting so sweeping, that he cannot avoid and cannot hide it anymore. Then he said, “Well, this is Biden’s fault.”

And so he’s doing something which has basically exempted the tariffs that he himself imposed and said, “Now I’m working on it, I’m helping the economy, I am reducing crisis by 300%, 600% or 900%.”

So next time you go out to buy a drug or a medical prescription Steve, you’re supposed to get money back, because that’s how the math is going to work. So I think all of this just shows that the US does have an active government, it’s just not working in the interest of the general public.

Now, I know your question is really asking about China and I’m sorry for going on so much on the US.

Steve Grumbine:

No, it’s all related.

Yan Liang:

Right? Because if you just see the kinds of glaring contradiction and irony, in terms of, this idea that the US is a free market economy right now, China does not shy away from the so-called ‘central planning’, that the government does play a very heavy role in the economy… For example, the 15 five-year plans.

So as you know, China had this five-year plan since very, very much early-

like in the 1950s, right after the founding of the People’s Republic of China-

that the Chinese government has been doing this five-year plan, and that is also, I would say enveloped right within this much bigger, also long-term goal, Like by 2030, we need to achieve certain economic goals by 2050.

So they have these very long-term goals that they see themselves to sort of work towards, and then they break that down to five-year plans.

And then with every five-year plan they, again, issue, every year, they launch these kinds of policies at the National People’s Congress. So then have the annual planning, and then five-year planning and then the much longer-term planning.

So for the very high level, the government is providing guidance to the economy, in terms of the big directions. So the five-year plan, from the very beginning, it has a lot of production quotas, so it’s much more of a quantitative plan.

But then at the early 2000s-

especially since 2006-

they kind of switched from very stringent quantitative planning, to much more qualitative planning, so set the big direction for the economy.

And so the language actually changed in Chinese, from the so-called Wǔnián Jìhuà, so five-year plan, to really Wǔnián Guīhuà… So, one word difference, which means the five-year guidance.

So again, but it does provide this long term, big brush kind of plan for the economy.

So the most recent iteration is to emphasize, again, we wanted to upgrade the traditional sectors with these technologies, and we wanted to achieve more technological breakthroughs and self-reliance. We wanted to invest more in the people, to have the people-centered development, and also high-level opening, deepen reforms and opening.

So these are really the sort of the big picture of how the government wants the economy to go in that five-year period. So this is just one example of how the Chinese government steered the economy toward a certain direction, and then we can talk about some of the specific measures.

But yeah, I’ll pause here.

Steve Grumbine:

No, I just remember years and years ago that the big knock on China was that they were currency manipulators.

They had pegged their currency-

I think it was like 7 yuan to $1 or something like that, I think that was the peg, it was like nine or seven, I can’t remember which it was when I was over there, just remembering the exchange rate-

and there were all these complaints about, “They’re manipulating their currency!” and now I’m looking back on it, I’m like ‘what do they even mean by that?’ I think the point I’m making is that China has always protected itself, and I don’t mean like as in with weapons, and guns, and tanks, and planes, and big, huge aircraft carriers coming around Venezuela for no reason, I’m talking about like, they just build their policy space, and the actions they take appear to be protecting…

what are some of these protections that they’re doing, like internally, to prevent the kinds of things that are happening in the US, if you will?

I mean it seems like such a radically different mindset of prosperity for real, not necessarily investor grade prosperity, but more like just quality of life investments. Am I missing something there?

It feels radically different when we talk about Chinese protectionism, or Chinese nationalism, or what the value system is that drives what they’re doing-

Going back to the five-year, and the 15-year plans, and the kind of guidance and so forth-

It really does seem like at least the purpose is to make life better. But what are the barriers they’re putting in, to prevent bad actors from taking advantage, and to wrecking the sauce, if you will?

I mean, Elon Musk as an example, just secured a $1 trillion payout from Tesla, I guess it was. Just ridiculous, I mean, shameful… That’s not really happening in China, people start trying to milk the system.

I mean, I’m hearing that they really don’t deal with that very kindly.

Yan Liang:

Yeah, absolutely. I think that gets very good to the point about using some specific examples to see how the Chinese government plays a very important, and I would say beneficial, role in managing its economy. So I think your prompt, has two aspects… One is how China protects itself from external risks, and then internally also, how China- unlike in the US-

giving this $1 trillion package to CEO, and again, a board of trustees approved this package, but of course with certain conditions that I’m not sure Elon Musk is actually able to meet… well, we can talk about that later-

but sort of internally, how the Chinese government is in some ways using these capitalists or entrepreneurs, but really I think, in a way, both guide them and provide certain guardrails to allow them both to thrive, but also really serve the purposes of the party of the people.

We can start with the protecting itself against external, some of the risks, and I think this is very important because we do know the world that we live in, this is still a very much dollar hegemon kind of a monetary or financial architecture at the global level, and so I think the protection is inevitable.

So as you probably know that China had the exchange rate reform back in 1994, where it basically lifted the control on its so-called current account. So in other words, if you want currency conversion for trade purposes, then you are allowed to do that, so you’re allowed to have the assets for foreign currencies.

If you are paying your imports or when you receive your export revenues, you can convert your foreign exchanges into the Chinese yuan, that is very much, sort of, less regulated. But the capital account control, which is like you said, the capital flows, so when foreigners want to invest in China’s stocks and bonds and other financial instruments, they’re very much regulated. China encouraged foreign direct investment, but it puts heavy controls on portfolio investment.

And when it comes to exchange rates- So, China never shied away from saying that it has a managed exchange rate system, and again, it’s very important that China remains this kind of control on exchange rate and capitals.

They really learned a lesson from both, the Mexican- and other Latin Americans- debt crises in the mid-90s, and also 80s… They also learned a hard lesson, I think, from the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s.

They understand if you completely decontrol your capital count and completely remove the control on your exchange rates, you subject yourself to a lot of volatilities, of these international capital inflows and outflows, that could both revalue your currency in a short period of time, and hurt your exports.

But more importantly, it could cause devaluation of your currency in a short period of time, when you experience capital flight.

Intermission:

You are listening to Macro N Cheese, a podcast by Real Progressives. We are a 501c3 nonprofit organization. All donations are tax deductible. Please consider becoming a monthly donor on Patreon, Substack, or our website, realprogressives.org. Now back to the podcast.

Yan Liang:

And another lesson that China learned is, back in 2015, when they really tried to move fast on their exchange rate, sort of, reforms. In 2015 they basically tried to lower their currency fixing by about 15%, so in other words, they artificially devalued the currency by 15%. Well, guess what happened?- Again, this is, sort of, in the context where, like you said, many countries, or many government officials and advisors in the US, that accuse China of being a currency manipulator, keep its currency artificially undervalued… that was excused. Some say that the currency is undervalued by 40%.

And you hear very recently, one of the prominent economists in the center for [Council on] Foreign Relations, the CFR, also argued that Chinese currency should revaluate by 20% to be able to adjust to so-called global imbalances. Okay, so the long story short, China does lower its currency value by 15% just by declaration in 2015, but what happened is that there is a very, very large amount of capital outflow, whereas the currency seemed to be on a free fall that year. The stock market tumbled, there’s a large amount of carrying, again capital outflows, to the extent that the Chinese government, in December 2015, they have to shell out $100 billion worth of its foreign exchange reserves, to sell these reserves to the market, in order to stem the capital outflows and to really prevent the free fall of its currency value. And so for the whole year in 2015, I believe they had to sell around $500 billion of foreign exchange reserves to stabilize the currency value.

Now just think about this… China was able to do it because it had over $3 trillion worth of exchange reserves at that time, so China was able to defend its currency value.

Now think about if this happened to another country that did not have this much of foreign currency accumulation, you could easily see a free fall of the currency, a devaluation crisis, hyperinflation and collapse of its financial system, and so on and so forth.

So I think this just, again, taught China a lesson, that this whole idea of capital liberalization is really, I would say, a Western agenda, a Washington consensus kind of agenda, and it could bring tremendous risks, and uncertainty, and harm to its economy. So I think that’s why China keeps trying to manage its exchange rate.

Now, I will counter the kinds of arguments that China undervalues its currency by 20% or 40%, and so on and so forth. Again and again, what we saw, was when China lifted control on its currency, it’s not inevitable that the currency is going to appreciate, there’s a very large chance that the currency actually could devaluate… especially if you think about, like you said, the potential ‘bad actors’ that try to speculate on the Chinese currencies, and so on and so forth.

So I think a managed currency, a managed capital account, is in the interest of China, and I think it’s in the interest of many, many other countries as well.

And I think even in the United States, people like [Trump Council of Economic Advisors Chair] Steve Mirren were saying that we might want it to control the capital flows, because if there are too much capital inflows, this could appreciate the US Dollar, and that could undercut the US export competitiveness.

So I think, again, all of this is just to say that the government should play a role in managing some of these very important economic- I want to say these kinds of tools-in order to protect this economy, to stabilize its financial order, to prevent this external vulnerability. Now, internally, I also think the Chinese government is telling some of its tech entrepreneurs that “we would like for you to innovate, innovation is a good thing, and we encourage you to do this.”

China just passed the Private Enterprises Promotion Law, again, trying to protect the legitimate interests and rights of these private entrepreneurs, but at the same time, the Chinese leadership makes it very clear that, “your technological innovation should be aligned with the government’s strategic goals and interests, we don’t want you to do too much of crypto. In fact, China banned crypto in 2021

[smart]

And I think that is very important.

Yeah.

So use technologies and encourage private entrepreneurs, but again, make sure that your interests are aligned with the national developmental interests, not to speculate and not to exploit people. For example, the crackdown in 2020, the so-called, they call it ‘regulatory storm’, where the government basically cracked down on some of the fintech, like the end financials and some of the super apps, the platforms where they do rideshare, and ask them to protect more labor’s rights, and so on and so forth.

So this is an indication that, yes, entrepreneurs are encouraged to do innovations, but they need to make sure they contribute to the economy, rather than simply just for personal or financial gains.

Steve Grumbine:

Right on.

So Yan, when we’re moving through this, and folks are watching the news and they’re listening to their favorite podcast or their favorite mainstream television station, or they’re listening to their President of the United States… where would people want to look to really, really get informed information about China? Because what I’m seeing right now, it’s almost lockstep, there is no deviation in the narrative, it is an institutional arrangement, I believe it is part of what Gramsci would call cultural hegemony, where this is just sort of the common sense that they’re preaching, and it spreads like wildfire, absent of facts, absent of insights. Where would they want to go?… Where would be a good place for folks to learn more about China, with less of the propaganda? Obviously, we’re trying to do a good job here on this podcast, but on a larger level?

Yan Liang:

Yeah, I was just going to say, I think for the general public, the platforms that you run here and others, the more progressive thinkers, for example, that are trying to report. Some of these places are where you can find, I think, more genuine understanding of China’s economy and engage China in a much more balanced way. Other podcasts, Sinica for example, and Trivium Podcast. Some of these are, I think, in a way, much more balanced than places like Fox or other outlets. And for more, sort of, scholarly

kind of work, I think looking into China’s own scholarly work, I think that is the way I would go.

And I think more and more, the scholars in China, they don’t just publish in Chinese, and they actually also have a lot of English language kinds of publications, where people can learn about their work. So, I think the main point here is to get different takes… get different sources and perspectives.

If you get mostly from the mainstream, even places like NPR I think a lot of times they don’t seem to have much more in depth understanding these days. So I would say, yes, you would have to explore different places where you get your information.

But also I think looking into even Chinese’s own media sources or scholarly community kinds of products, so in a way, you can be more balanced.

There are people of course, that would say places like Global Times or the China Global TV Network [CGTN], they are the Chinese propaganda, but what I would say is, if you keep getting stuff from US mainstream media, then getting a little bit of the other extreme, wouldn’t be a bad thing, because then you really kind of see how these kind of different perspectives could intersect or interact, so you can get a little bit more, sort of, balanced view in that regard.

So I think, again, I’m not blaming people for not getting the right source of information because it is very difficult.

The US Congress has authorized, I believe it’s a $1.6 billion budget for anti-China propaganda, and so they literally giving out money to people to do videos or do podcasts.

I think at one point I read some stats about the giving money to people from Africa, for example, the bloggers or YouTubers, to produce one anti-China propaganda video for $7,000 or something like that. So, it is a big machine out there that’s try to spell all these anti-China narratives and propaganda.

So I think it’s difficult for the general public, that you’re not every day thinking about what is behind all these narratives, or what is behind all this rhetoric, and what is behind all this propaganda, to really get the right source of information. So it is a difficult undertaking, but I again, would encourage people to do that because again, day in and day out, when you get this wrong information about China, either you overplay China or you underplay, and either way it’s going to be harmful to your own good.

And I think, again, just looking at Trump’s tariffs and also export controls, the tech control, trying to, kind of dampen China’s technological innovations or China’s development, I think, again, they probably get a lot of misinformation from their own think tank, thinking that because the US has the largest consumer market, that they can play China. China does not have leverage, but I think they really underestimate China’s important role in the global supply chain, especially in terms of the rare earth controls.

And now, I think there’s also some realization that China is also holding a lot of critical ingredients to the pharmaceutical industry, I think in the US there are 700 critical medicines that have at least one key ingredient that they source 100% from China.

So that could have been another choke point in the US’s, sort of, vulnerability. And again, I don’t think the Biden administration, to now Trump administration, they don’t really understand completely China’s, sort of, leverage and China’s really pivotal role in the global supply chain, and so I think they really miscalculated. And again, one of the reasons is because of this, kind of, ignorance and hubris, to think that the US always has the upper hand, and even in the AI race, this idea that people seem to get surprised, and surprised again and again by China’s breakthroughs.

If you are a China watcher for the past decades, you shouldn’t be surprised at all, you really see that coming when China is putting up all these programs, and investing so heavily in the global supply chain, from the very upstream to the very downstream, and also beefing up its education, R and D and all these facilities, infrastructures… it shouldn’t be a surprise at all.

But I think the policymakers and their think tanks seem to keep getting surprised, because again, they don’t really understand China at a granule level, or at a big picture level.

That is very unfortunate and that could lead to miscalculations again and again, to the detriment of the US, but also I think it’s very disruptive to the global economy as well.

One last interesting thing that I wanted to mention is, you probably know this think tank called Rand Corporation [R *A *N *D*]-

it’s a very much Washington DC, sort of… It’s a high-level think tank, has the ears of many of the policymakers, especially in military and defense industries, and so on and so forth-

Very recently they published a report that was basically advocating for ‘three major reasons for peaceful coexistence with China’, but after the report was published, very quickly-

I think within weeks-

it was retracted.

And now if you go to the website, it says ‘this report is retracted for further considerations.’

So it just shows that when you put out a genuine understanding and somewhat different kinds of opinions or perspective, it was pretty much cramped down. And so we kind of see going back to the same kind of path, keep saying that, “China is weak, China’s collapsing”, or the other day was, “China is eating our lunch.” The pendulum swings back and forth, that really doesn’t help to craft, both genuine understanding, but also response to China.

Steve Grumbine:

I do have three more key questions to kind of guide us through the rest of this, and I’ll just jump on this. We’ve touched on pieces of this, but this is an MMT podcast… Yes, it is a class-based podcast as well.

We like to understand the implications of all these grand ideas on the working class, but in particular, through a geopolitical lens. Obviously, that includes the rest of the world, and we’ve talked a lot about empire in past, we’ve talked a little bit about China’s perspective, but I am curious, because putting this together with MMT as well, I think is really important for the work we’re doing here. I’m sure for people that listen to podcasts like this, they’re like, “Okay Steve, you got an MMT economist on, when are you going to talk about MMT?”

But to me- I want to just put this out there in a way and I’ll let you respond to it- The US uses its dollar sovereignty to project power globally, through military spending and sanctions.

China’s also expanding its global influence, through initiatives like the Belt and Road, which we’ve talked about on prior podcasts-

Folks, look in our backlog, we got lots of good stuff there-

but we can touch on a little bit here.

How does China’s different monetary framework-

and this is the key, I don’t know enough, I mean, I understand a fiat currency, but we talked a little bit about currency controls, and how they work with the exchange rate and so forth-

But how do they use their vast foreign exchange reserves, etc., to shape the type of international influence they have, compared to the US that uses things like the IMF [International Monetary Fund], World Bank, structural adjustments, privatization… just horrible, horrible approaches to everything. How does China do that?

Yan Liang:

Yeah, I think that’s a great question. And I think now that you mentioned monetary sovereignty, I think I should also go back to earlier,

that a lot of these- management of exchange rates, control capital flows- all these are really trying to preserve monetary sovereignty, to make sure that when you use active fiscal policy and monetary policy, you’re not going to be subject to the kinds of exchange rate volatility, and capital flight and so on and so forth, that could derail your monetary sovereignty, your fiscal and monetary policymaking autonomy.

Now, onto this idea that how China is using its monetary sovereignty to advance its own interests, both domestically and internationally. So, just to say that.. well, first of all, I think the Chinese policy-making circle, or if you look at their official policy, they do have these kinds of fiscal rules, they do say, “Well, we want the deficit to GDP ratio to be 3% or 4%”, 4% actually is 2025’s target.

So seemingly, they have these sort of targets, that they don’t want it to so-called ‘overspend’, or they want it to have the, kind of, fiscal discipline, but at the same time I think that the Chinese government is well aware of the power of these fiscal and financial resources.

So as you probably know, that in China, the state-owned enterprises or state-owned banks, they’re still really strategic industries. So the state-owned enterprises, they’re in places like utility, energy, telecom and financial sectors.

The reason that I wanted to mention this is that these state-owned enterprises and banks, they still control a very large amount of critical resources within the economy, and so they are able to use these resources to advance the national strategic economic goals.

And that is very important, because for MMT what is important is how much real resources you have, and how do you expand the resources boundary.

And so, I think what China has been doing, is they’re using these physical resources and financial resources, to be able to mobilize resources and expand resources domestically. So very briefly, for example, there’s been these findings that said that China’s industrial policy spending is close to 4% of the GDP.

Now, I don’t want to go into, sort of, whether or not that number is accurate or not-

what counts as industrial policy spending, what doesn’t-

But let’s just say that 4% is correct… But then so what?

I don’t think this is the way to say that China is misusing its spending, because we clearly see how China has become a manufacturing superpower, accounting for 30% of the global manufacturing capacity, and it is making so many breakthroughs in many of these technologies.

So, I think what this shows is it attests to the fact that the Chinese government understands the power of financial resources, and uses them in a way that would help China to industrialize, re-industrialize and improve its industrial structure.

Now externally, I think, is what you are sort of prompting in your question, I think what China has been doing in the past decades-

the BRI started in 2013, but China’s sort of going abroad started in the early 2000s-

So in the past 10+, 20 years, China has been really providing very important development finance, to the tune of $1.3 trillion to the rest of the world. So to this day, you can see a lot of these mega-infrastructure projects in, Africa, in Latin America, in Europe, in Southeast Asia, in Asia, in various places where I think China is really enabled many of these countries to build their own infrastructure, to build their industrial structure. I mean, when it comes to, for instance, renewable energies, China now is basically producing 80% of the global supply of solar panels.

And China is accounting for two thirds of the global renewable energy.

And China’s exports of the so-called low carbon technologies and products to the rest of the world, have enabled them to really cut their own carbon emissions. I mean, my colleague at the center for Global Development Center, the GDP Center, have shown in academic papers that this is a fact.

So in a way, I think China is providing very critical development finance, and products, and technologies-

So, these are three different things, financial resources and also green products like EVs, like solar panels, like batteries, as well as green technologies-

to the rest of the world.

And I think that is really important, to enable and facilitate the kind of sustainable development in the rest of the world.

And of course, trying to benefit from this kind of partnership that China is able to export more of their products to the rest of the world. Now we can, again, talk about whether or not that is in China’s own interest, to keep giving real resources to the rest of the world and so on, or China is exporting too much. And again, we need to contextualize that, I think when it comes to the net export to China’s GDP ratio, it’s really small, it’s much smaller than countries like Germany, or Japan, and so on and so forth.

But because China is big, I mean, even if China just exports, net exports 2% to 3% of its GDP, it could still be “a shock” to many of the countries, especially I would say, the Western economies, where you hear all these complaints about China’s overcapacity, is actually in these Western advanced economies. Why? Because China is eating their cake.

German car companies, US car companies, they’re all sort of worried about China, because China’s EV is very competitive, and so they’re really worried about China climbing up the global supply chain or the value chain. This is exactly what J.D. Vance says, ‘when China was a good player, was China basically stuck in the low-value chain, that was okay, when China joined WTO [World Trade Organization].

But now it’s not okay, because China somehow climbed up the global value chain.

So it’s not that China now all of a sudden became a bad actor, because it violated the global rules, or trade rules, or anything like that, but the mere fact that China is able to get more value added and climb up the value chain, no longer exporting 800 million T-shirts to import one Airbus plane, when now China is actually trying to make their own airplanes.

I think that is what worries the Western world, and therefore have all these ‘overcapacity’ claims, and mandate China to fix the problem. I mean, why is that only China’s problem?… If China is running a trade surplus, why is it not the US’s problem, when day in and day out they’re running trade deficits and getting the real resources from the rest of the world, given its currency status? I mean, we can go on and on with this.

Steve Grumbine:

Yes, please.

Yan Liang:

Yeah.

So I just think that China’s development finance is helping the rest of the world, so is its supply of these critical green products and technologies.

Now, I think the caveat here is, of course we know that many of the developing countries, especially low-income countries, are now in the midst of debt crises. The UNCTA basically put out reports that shows 3.3 billion people live in countries now, that paid more for their foreign debt-

when it comes to debt services-

than what they spend on healthcare and education. So that is a problem, and I do think that China should- and has the resources to- do more, to help to fix these kinds of debt crises in developing world.

But I think China’s hesitancy also comes with the fact that China only accounts for a much smaller proportion of the developing countries world debt, compared to the bondholders, the private creditors. So China feels like, ‘if I give a lot of debt relief, then what about all these other private bondholders?… They are not giving haircuts, they’re not giving their own share of debt relief… and so whatever I forgive then, would simply be pocketed by these private creditors.”

I mean, there’s some kernel of truth to that concern.

And so, I think that really requires a lot more collective, I would say a more multilateral system, to resolve these kinds of debt crises.

I think the solvent debt roundtable is a step in the right direction, but it’s too slow and too little at this point, and much more needs to be done on that front.

And by the way, I think there was a very recent report that was put out by the Center for Global Development, that shows in the past decade, that China actually lent $200 billion to one country, which is the largest country that received China’s loans. Now this is not direct investment, this is not contract and whatnot, this is just the lending.

Guess which country that is Steve?

Steve Grumbine:

Dang, which one?

Yan Liang:

Yeah, which one?… that received in the past decade $200 billion of Chinese lending… One country: the United States!

Steve Grumbine:

I was letting you go to the punchline… Of course!, of course it is. I mean, that’s ridiculous, it’s hilarious.

Yan Liang:

Right? I mean that just says a lot of things, for one, why does the United States want to borrow from China? The US has the dollars, why do they do that?.. Why do they want to borrow from China? I mean, this is nothing really new, we know that China holds right now about $700 billion of treasuries, so China has already been a large creditor to the United States, but here we’re talking about more of the private, sort of, sector of borrowing from China. So to me, from an MMT perspective, there’s so many kinds of things going on in here, which is kind of really weird.

For one, why does the US need to borrow dollars from China? For two is, that the US keeps telling other countries not to borrow from China, calling this debt-trap diplomacy, but the US ends up being the largest borrower. And also, to me, there’s also the question about why does China want to lend to the US?

Maybe they want to diversify their portfolio? Maybe they just think that this somehow provides some gains?.. but not really. I mean honestly, I’m really puzzled by this.

But anyway, I think China could really do more to provide different financing to the rest of the world, especially given now, how cheap the Chinese lending is, and how expensive the dollar lending is.

And that’s why I think countries-

like Kenya, recently converted their dollar denominated $3.5 billion loans to China, now to RMB [renminbi], and I think many other countries, Ethiopia, and Indonesia, and many others are also considering doing this kind of currency conversion of their debt.

Because again, this is a tremendous amount of savings on their interest payments, because China’s lending, again, is cheap, 2%, 3%, compared to the dollar loans that could go up to 8%, and even more…So, yeah.

Steve Grumbine:

Is there any consideration of China using its dollar holdings to, in fact, free the rest of the world from US imperialism?

Yan Liang:

Wow, that’s a very intriguing question.

I think we discussed a long time ago about this idea, that maybe China can just use these dollar reserves to provide debt relief to the rest of the world. And again, China has its own hesitation.

For one is, they do want to keep large amount of foreign exchange reserves to protect themselves, as we earlier mentioned

Steve Grumbine:

Sure.

Yan Liang:

And for two is, I mean, from China’s perspective, they don’t think this is in a way, sort of fair. From China’s perspective, they have been providing development finance to the rest of the world, and again for very productive uses.

China is not giving this financing to, let’s say for corrupt governments to pay for their officials’, I don’t know, private mansion or whatever. Or they’re not giving this as aid, that would hold the countries on and on to coming back for more aid.

China sees its development finance as capacity building, so they have very specific project height financing.

So they’re providing $3.5 billion loans to Kenya, not to let them spend on anything they see fit, but this is exclusively to finance the construction of their standard railway.

So, what China considers the lending that China has been doing, or development financing that China has been doing, is really for productive uses, and that generates productive returns and helps the countries to climb up their own industrial ladder.

Steve Grumbine:

Yes.

Yan Liang:

So China doesn’t see that they’re using the money in an unproductive or malicious way, and so to them, it’s legitimate for them to get a return, to at least get the loans back.

And again, they’ve been providing really good terms when it comes to lendings. So the standard gauge way loans, the fixed portion is only about 2% interest, we’re talking about 15-year infrastructure loan, part of it is only 2%, part of it is Libor plus flexible range.

But still overwhelmingly, I think the Chinese loans are much, much more affordable, than compared to a country on the Eurobond market, that could easily pay up to 8, 9, 10% interest, compared to China’s 2%, 3%, 4%, etc.

So for China, it sees itself providing these kinds of development financing and affordable terms for productive uses, so it doesn’t see the need to massively forgive these loans.

And I think in some ways, countries also try their best not to default on their loans, and try to pay some of these debt services, because they don’t want it to cut the source.Of course, China will worry next time around if these countries come back and ask for new loans, China will consider whether or not they’ll be able to recoup their loans… And so for this reason, I do like China to provide more debt relief to the rest of the world.

But I think it’s not very feasible, not very practical at this point, to think about how China may use its large amount of foreign exchange reserves to free the rest of the world from the dollar trap.

Now, I will say though, China has been trying to promote the RMB internationalization, to encourage more international uses of RMB, and that’s why you’re seeing that China is now trying to stabilize its exchange rate values. Not to appreciate, not to depreciate, really to have a very stable fixing.

And also, given that the yuan [the basic unit of the renminbi system] interest has been low, that many more countries are more willing to seek Chinese financing, issuing Panda bonds, dim sum bonds and things like that, which are RMB-denominated bonds.

So, I think I do see that, kind of, position that China is taking, which is to promote more uses of yuan, not necessarily to displace the dollar, but at least to create some optionality and provide some kind of counterweight to the, really, dollar-centered system. So I think that is a step towards the right direction, because if we’re talking about a multipolar world, we need multipolar currencies.

Steve Grumbine:

Yeah.

Yan Liang:

And so, I think China is working on this, yes.

Steve Grumbine:

Very, very good… Well stated. The last question-

and I do appreciate how patient and wonderful you’ve been-

So, this last question, in my opinion, I think is worth noting, because so much of what we hear-

and you’ve already addressed some of this-

is the US talking heads, and these, kind of, mainstream media talking heads, talking about how, “China is set up for a fall!” And you already laughed us through it, it was great, the way it was like ‘keep waiting for it’, but it never happens because it’s not going to happen.

However, what are some of the areas within China that are potential weaknesses for them, that they have to address? And how might an MMT lens facilitate, kind of, correcting or fixing any of those errors?

Or quite frankly, do they just already have plans for it, and they are insulated from some of those major spikes, and ebbs, and flows that we see so characteristic of a Minsky Moment in the United States? How does China avoid these kinds of instabilities? I know you talked about managing the currency at some level, but it goes beyond that… What are some of the things that China has to guard itself against?

Yan Liang:

Yeah well, I really appreciate that, you always have the more balanced view on China.

So, I think we have talked a lot about the positives of China, which I think, again, these are fact-based, but they’re definitely challenges that China is facing. So I think the Western narrative always talked about China’s collapsing because of the Four D’s (Duck, Dive, Dip, Dodge)… The DEMAND is very weak… It faces DEFLATIONARY pressure… The DEMOGRAPHIC time bomb-

because ‘China’s aging very rapidly, and the Chinese could get older before they get rich’-

And lastly is this DE-RISKING… Decoupling from the West, that could, again, put China in a very vulnerable position.

So, I’ve written working papers to kind of, debunk some of these narratives, but I think there are some questions, or there are some challenges, that China needs to try to resolve.

One is, this idea of deflation, which we know that in China, yes, there’s some kind of disinflationary pressure. So, it’s a CPI, for example, just barely 0.2% in October this year.

And that is actually the first time in three months, that the CPI finally turned from zero, and negative to positive… But as you know, 0.2% is a very low rate, in terms of inflation rate.

Now, I would say that one of the major reasons, is because this disinflationary episode, to me, is looking less like the US in the 1930s-

when you had this deflation depression-

It’s more like in the 1870s, when you had major technological breakthroughs.

The supply expands much faster than demand, rather than a negative shock to demand… That’s not what’s happening in China. Demand is still growing, consumer spending-

especially in services-

is still growing tremendously.

The retail sales grew by 4% this year so far, 4.3%… And you know, in terms of service consumption, it’s over 6%. I think, if my memory serves me well, it’s higher… It’s a good pace of growth.

But the problem is that, there is tremendous amount of supply expansion, when you go to China. When you look at all these robot adoptions and automation in factories, Xiaomi, an EV Company… they are able to make one car within, I think, 70 seconds or 90 seconds. It’s just the tremendous amount of supply expansion, that far outplays the demand expansion. I think that on top of that, a lot of competitions among these private enterprises, EV brands, there are over 150 of them and they put out new car models every 16 months. This is how fast innovations and production capacity expand in China, so that’s why it creates-

what Chinese call-

the involution.

So like, a very fierce internal competition and that drives down prices.

And so I would say on the one hand, this is good because it helped to provide affordable abundance, this whole idea of abundance that China’s actually doing-

which in the US, we know these two journalists who wrote this book about abundance, and people think that this is still a dream, that in the distant future, or in the hopefully NOT so distant future- Now, China’s already doing it, it is prizing people, a car used to be a luxury… no longer. So, I think that to some degree this is actually a good thing, it provides actual value to the consumers.

But on the other hand, when you are not generating a healthy profit margin for these companies, and when you have this expectation that price is going to keep falling, we know this could wreak havoc on the economy or could at least do some damage to the economy, because then you are waiting to buy the next car, or companies are just waiting to invest. They’re not doing it right now because expecting the price will go down further. So that is not necessarily good, right, or healthy or sustainable for the economy. So I think China needs to strive a balance to rein in some of these involutions.

And you know, we don’t have the time to talk about how exactly this should be done, but suffice to say that I think the government is well aware of this problem, and even back in June this year, they already asked the companies to not to have the kinds of cutthroat price competition, and compete more on your new features, on your new innovations, and so on and so forth. And they’re also warning the local governments not to unconditionally support your local champions, to engage in this kind of price war.

So that’s number one. I think that disinflation could be a problem, but I think China’s government is managing that.

Now, in terms of debt, I don’t think this is a problem if the central government is willing and able to step in and help out a bit more on the local government debt. Again from an MMT perspective, I think what worries me or what concerns me, it’s not the overall amount of public debt, but this inverting structure of debt, in the sense that the central government only holds about 20% of GDP, sort of, amount of public debt, whereas the local government is holding a lot more, easily double, the amount. And so, I think that is a problem because local governments don’t have the currency sovereignty, they can’t just issue the currencies or create the currencies.

So I think the central government needs to take on more debt, and relieve the debt burden of the local governments, because the local governments, they are only accounting for about half of the total fiscal revenues, but they are accounting for over 85 or 86% of the public spending. So you can see the mismatch is going to create problems, because once the local governments are too much in debt, they’re not going to continue to spend, they’re not going to continue to finance infrastructure, they’re not going to continue to provide public services and welfare to their localities… And so that could be a problem.

So for me, it’s not a debt crisis, but rather, it constrains the fiscal spending at the local government level, and we can talk about others, but I don’t think others are really the major problems.

The real estate sector is sort of a drag on the economy, and I was hoping that by the end of this year, we’re likely to see the real estate money hit the bottom, but I think the most recent data has shown that the real estate sector is still quite, sort of, in that slump, 12.7% decline in the fixed asset investment in that sector.

Now again, I think the sort of readjustment away from the real estate sector, I think it’s a good thing because there’s too much investment in that sector, too much leverage. It’s not good for an efficient allocation of real resources.

But at the same time, because the real estate sector is still very important for the Chinese households. The housing value is about 70% of household wealth, so when your real estate sector continues to see declining prices, this is going to create some kind of negative wealth effect on the households.

So, I do think the government should do a little bit more to stabilize the real estate market, and also utilize the unsold properties, use them for social housing.

[Yes]

We’re building so many houses… and China, by the way, has over 93% home ownership, as compared to Western economies, exceeding 50% is a great achievement.

Steve Grumbine:

Yeah.

Yan Liang:

So, I don’t want to say the real estate investment is a complete waste, it’s not… But we definitely can do more to utilize the housing.

You know, others talking about demographic crisis, I think it is a slow transition into an aging society, and I think with productivity growth, with educational attainment, improvements, and also with automation and adoption of AI and all of these, I think it will help to relieve the labor supply-side constraint. I think it’s actually important to create more jobs for young people in China right now.

So when you hear people talking about demographic crises, that ‘China don’t have enough labor supply’, I think the reverse is more of an immediate task for the Chinese government, to actually create better jobs for the young generations.

So, it’s actually not the problem of too little labor supply, it’s that now we have these college graduates that are yet to be able to find a job that fits with their skill sets, and so on and so forth. I think that is more of an immediate task on the part of the government. So I think those are the challenges… Job creation, Disinflation, Inverted Debt Structure and also the Real Estate Sector Stabilization, to boost more consumption and domestic demand, and find a way to create more investment opportunities, especially on the infrastructure, actually.

I think those are the challenges right now.

Steve Grumbine:

That’s very well said. I have so many more questions, but we’re out of time and I want to thank you for giving me the time you’ve given me today.

Yan, tell people where they can find more of your work.

Yan Liang:

Yeah, so now I am working a lot on China’s role in the global financial architecture, so my work has been focusing on one working paper right now… Well actually yeah, one working paper about China’s debt sustainability framework [DSF], China’s own DSF framework.

So that would be published very soon by the GDP Center, the Global Development Policy Center as a working paper.

And then I have a co-author paper, that hopefully will be accepted and published soon, that is looking at China’s lending to the rest of the world, and again, to debunk some myths that China extracts financing from the rest of the world, instead of injecting to the rest of the world… That’s another paper that I’ve been writing.

And then I have a paper that is close to completion about R and B internationalization, and then another one about reforming the special drawing rights at the IMF, to provide more debt relief and development finance for the Global South. And then one last paper that I’ve been working on, is on the common payment system within the BRICS.

So all of these are in different places, some of them are with the GDP center, as I mentioned, and others would be book chapters, and also would be working papers for the International Development Economics Associates.

So, I would probably post when these papers are published on my LinkedIn account, and I’m also active-

I mean, not that active-

but sometimes I will be on X, mostly to show some of my media engagements, and also when- occasionally, there are some posts on X that really get on my nerves, then I’ll respond.

So yeah, so those are the places where you probably can find my work, again, LinkedIn, X and also with some other affiliations, the Levy Institute and the GDP Center and IDEAS. Yeah well, thank you again… I really appreciate that, I feel like I talk too much but…

Steve Grumbine:

Not at all.

Yan Liang:

You know, this is a fascinating topic and it’s really dear to my heart.

And I really would like to share with you and your learning community, your audience, and maybe at some point, if there’s any interest, we can decompose the big topics and maybe focusing more either in China’s internal economy or external, engagement or what have you, or the US China relations or anything along those lines. I’m more than happy to join you, Yeah.

Steve Grumbine:

Count on it… Absolutely. Alright, so I’m going to take us out here… Folks, first off, thank you so much to my guest Yan Liang.

My name is Steve Grumbine, I am the host of Macro N Cheese. This podcast is part of Real Progressives, which is a 501c3 not for profit organization, here in the United States.

Your donations are tax deductible, folks. Don’t assume someone else is donating… They’re not, I promise you, I look, they’re not… And we need your help.

So at this time of the year folks, as we head into the final quarter of 2025, if you’re looking for an opportunity for a tax deduction, please consider Real Progressives, which is a 501c3 as I stated.

Also, we do a Tuesday night webinar called Macro N Chill, where we discuss these episodes in detail, in a community setting. 30 to 40 people show up ready to go ahead and talk about these things… And sometimes our guests join us, hint, hint… Other times they don’t join us.

But we would love to have them at all times, because we have people that are voraciously looking to learn these things, and we consider ourselves to be a source for that. Also consider becoming a monthly donor on our Patreon. Realprogressives patreon.com /realprogressives.

You can also go to our Substack and become a monthly donor or a single time donor… We don’t turn our nose up, folks. And you can go to our website, realprogressives .org and make a one-time donation, or whatever you’d like.

We really need your support.

And one final thing, and this is a note I think, for all activists and all people that find this kind of information valuable. Folks, we don’t have an advertising budget, you are our advertising budget. On social media, simply clicking like and share is a huge help to us, It’s free and it takes seconds.

We would love to encourage you to consider doing that minor act of solidarity… I know a lot of people just assume someone else will do it. They’re not… We could really use your help.

Please, if you’re on X, or you’re on Facebook, or you’re on YouTube where we publish these things as well… Please consider sharing the content. Somebody will thank you, mainly me.

So with that, Yan, thank you so much again, and on behalf of the organization, and Yan Liang and myself, Steve Grumbine… Macro N Cheese—– We are OUTTA here.

End Credits:

Production, transcripts, graphics, sound engineering, extras, and show notes for Macro N Cheese are done by our volunteer team at Real Progressives, serving in solidarity with the working class since 2015. To become a donor please go to patreon.com/realprogressives, realprogressives.substack.com, or realprogressives.org.

Extras links are included in the transcript.

Related Podcast Episodes

Related Articles