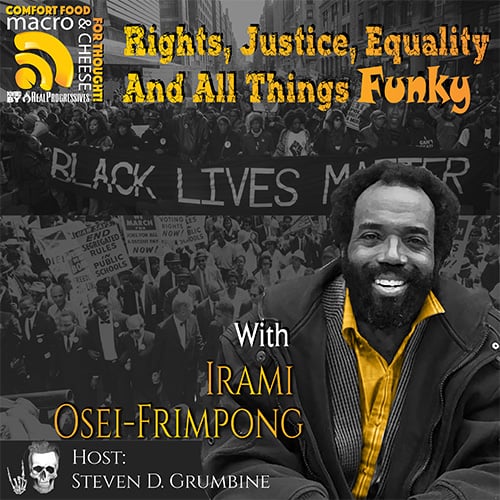

Episode 73 – Rights, Justice, Equality And All Things Funky with Irami Osei-Frimpong

FOLLOW THE SHOW

Our guest Irami Osei-Frimpong (the Funky Academic) will make you laugh. He also delivers truth like a gut-punch. Don't miss this episode.

If any of our listeners aren’t following The Funky Academic on his website, YouTube, or Twitter, this episode will change all that. Macro n Cheese usually leans heavily towards economics, but Irami Osei-Frimpong arrives at many of the same conclusions that we do, yet gets there by a different route. That helps make this such an interesting interview. In these disturbing times, his strong sense of humor and irony are a welcome respite.

Irami is a PhD student in philosophy, which he chose to study because, as an undergraduate, he realized that people are confused about what justice looks like. In a liberal democracy, there’s no need for a minister of propaganda; our thinking is controlled by what is omitted from our education. He says we must know what we’re fighting for because if we’re merely guided by emotions or compassion, we can be easily confused and swayed. “You need actual arguments to ground you so you’re not buffeted about when your latest crush is a Republican.” This is how we end up accepting that there’s a “natural” rate of unemployment, for example.

The episode is full of astute observations about racism, economic insecurity, and the indisputable necessity of a Federal Job Guarantee. Alton Sterling was selling CDs from the trunk of his car, and Eric Gardner sold loose cigarettes. Imagine if they had guaranteed jobs that paid a dignified wage, which Irami maintains should be $22 an hour. We don’t want a living wage because we want to do more than just live.

Irami draws lessons from history as much as from today’s headlines and he often ponders the concept of citizenship. How can we participate in the political process while dealing with unemployment? In a nation of laws, how can we exercise our rights as citizens if we can’t afford legal protection? He tells an anecdote about Hulk Hogan which illustrates why we need a single-payer legal system as much as we need single-payer healthcare.

Steve and Irami discuss the marijuana business, reparations for African-Americans, and unprovoked police shootings. While the interview is laced with humor, the themes and implications are dead serious.

Irami Osei-Frimpong is a PhD student in Philosophy at the University of Georgia.

Check out his website:

funkyacademic.com

@IramiOF on Twitter

Macro N Cheese – Episode 73

Rights, Justice, Equality And All Things Funky with Irami Osei-Frimpong

Irami Osei-Frimpong [intro/music] (00:00:03):

One of the ways of living in a police state is having the police take 45% of all of your tax dollars. So even if you’re not living in fear of the cops, the fact that the cops have so much of the public treasure means that we are de facto a police state, because that’s where all of our treasure goes.

Irami Osei-Frimpong [intro/music] (00:00:24):

There are a good number of white people who think that if Black people have power, that they will be like white people and that terrifies them because they know how awful we make white people.

Geoff Ginter [into/music] (00:00:39):

Now let’s see if we can avoid the apocalypse altogether. Here’s another episode of Macro N Cheese with your host, Steve Grumbine.

Steve Grumbine (00:01:28):

And yes, this is Steve with Macro N Cheese. Today, I have a special show. Given the circumstances that we are living in today, and really in fairness, this has been going on for the beginning of the dawn of this nation. We are under incredible stress and we’re watching as real revolution is taking to the streets.

We’re watching people saying we’ve had enough and here at Macro N Cheese, we largely focus on macroeconomics, but it’s important to understand the impacts, the societal impacts that an unjust economy, an unjust nation, a nation with laws that are unjust has had on people of color in this nation is been a travesty and we are seeing finally a unified front come forward and try to fight back in whatever fashion they can, especially given a pandemic.

And so I reached out to a gentleman who I find to be incredibly intelligent, incredibly witty, and insightful and his name is Irami Osei-Frimpong, and Irami is a PhD student at the University of Georgia in Philosophy Department. He runs a website, the Funky Academic, where he tries to convey basic concepts in the History of Philosophy in a way that helps people think through their lives. And so with that, I want to say, thank you so much for joining me, Irami, I really appreciate you joining us.

Irami Osei-Frimpong (00:03:05):

Thanks for having me on. This should be a hoot.

Grumbine (00:03:08):

Well, we talked for quite a bit before we got started, but I really am incredibly impressed with the razor sharp line that you walk in terms of being able to be academic in your face and also an activist. That is an incredible triumvirate right there. You’re really well put together in terms of being able to create the understanding, the impact of your statements. I guess basically tell us a little bit about yourself before we get too far into my fanboy here and then we’ll go ahead and get deeper into the meat of the subject.

Osei-Frimpong (00:03:47):

Yeah, I’m a PhD student in philosophy, and I came to philosophy, not through the obvious way, because most philosophy grad students you’ll find out that their parents were philosophers or their parents were academics and my parents weren’t. But I realized rather early in my undergrad that we were just confused as a people, on what justice looks like and there’s this great quote by a guy named Hutchins.

He ran the University of Chicago for a few decades in the early 20th century and he’s like, “Look, people talk about they want justice for the Negro. They want justice for the third world, but then you ask them, ‘What is justice?’ And then they don’t have any idea.” And that’s a problem, right? Because if you don’t actually know what you’re fighting for and you’re just doing it for like compassion or because it makes it feel a certain way, then you can be easily moved.

You can be confused about what you’re fighting for and why, and you could be easily dissuaded from the right opinion. So you need actual arguments to ground you so you’re not buffeted about by, you know, when your latest crush is a Republican. So like you need some sort of standing about like why freedom matters and why justice calls for certain policies and why we don’t need to be okay with the standing vulnerability of entire communities in ways that I think we are.

And you have to watch this carefully in a liberal democracy because you know, you’re never actually taught what justice is or how it’s structured or what it even means and that’s how in a liberal democracy, they get to you. They don’t have a minister of propaganda, like, you know, an authoritarian state. What they do is they just leave out the important stuff that you need to know.

So you feel like you’re making choices based on bad information. Like we don’t know that the government pretty much prints up money until there’s a pandemic, and then we watch the government makeup somewhere between $2 to $6 trillion because it felt like it. Like, so it couldn’t hide it. Right?

Grumbine (00:05:38):

Right.

Osei-Frimpong (00:05:39):

So, you have to watch what is left out of your education, which is one of the reasons why I try to do public philosophy as publicly as possible because what’s left out of our education makes us complicit in some really awful institutions that are preventable. Right? And we just think it’s natural that we have a homelessness problem. We just think it’s natural unemployment.

Isn’t that the phrase like natural unemployment . . . There’s nothing natural about it. We just design another scheme where people actually have access to good jobs and empowerment at workplace and live lives with vacations so that they can take their family for a weekend camping and these are all political decisions that we can make if everyone has kind of the knowledge and the arguments to understand what justice looks like and their responsibility to uphold it.

Grumbine (00:06:30):

You know, it’s funny you bring up the unemployment there and the natural rate, etc. It’s funny that Milton Friedman got a Nobel Peace Prize. I always sit back and I say, “Wow, you got to wonder what they were thinking. I mean, how does a guy that is the master of austerity get a Nobel Peace Prize? It doesn’t make sense.”

Osei-Frimpong (00:06:54):

So much is trauma and tension. Well, look, we’re in a market society, right? So in a market society, either you are a producer or you work for someone so you have your goods and services that you put on the market. But we’re an industrial society, which means that the market actors are very big. So I’m not going to be able to compete with Walmart. People don’t know that, you know, when the country was founded in 1776, this was pre-industrial, right?

So it was the assumption that everyone was going to be a small business owner. Well, all the men were going to be small business owners who weren’t in the South because they still have like the slave economy, but it’s a pre-factory economy and even like our economic theories, when you go back to Adam Smith, the famous pin factor, he talks about where like, if we divide up labor, everything’s more efficient.

He was talking about a factory of 10 people, right? He wasn’t thinking about an industrial economy where the smallest business, according to the government, a small business is 500 employees or less, which means that in order to like participate in America, you’re going to be one of the very few people who actually own a business, or you’re going to be one of the 95% of the workforce who works for somebody, right? And you’re not going to be able to compete with a Walmart.

You’re not going to be able to just like, start your own shop and compete with an Amazon anymore because we’re an industrial society. So if you’re not going to guarantee people like land, like we did with all the land you could take from a Native American, like we did with the what’s called the Homestead Acts. You got to guarantee people a job. And so it makes sense when you walk through the argument and when you walk through our history and the presuppositions that went into kind of framing our political thought.

But unless you know that you just assume that, well, the natural unemployment makes sense, but really you’re not free and that’s the argument I need people to make. You’re not free in a market society, unless you have power in the market. That means power and consumption and also power in production. You need to be able to shut down production, which means you need a job. You need to be a place in civil society and a job that’s not exploitative so that you actually have power in the workplace so you can shut it down or work with other people to shut it down.

If need be. And one, that’s just not just living wages. I don’t like the living wage because we want to do more than live. We want to be free. So it’s not just a living wage. I like a freedom wage, but that’s even more than a fair wage because a fair wage is kind of individual. I get paid fairly based on, you know, whatever shareholder profit of whatever firm I’m working for. I get paid fairly. But if I’m around people who are poor, if everybody in my neighborhood is poor, I might be paid fairly, but I’m not free.

I can’t even go outside without getting hit up for money. Freedom means being able to go outside and talk with your friends without being the only one with a job, right? So if we’re talking about real wealth and real freedom, I need not only me to have a job, I need everyone I’m around to have a job with disposable income so that we can like, you know, come together and form a social club or, you know, dude pay dues at my church.

You’re not free if you’re the only one at your church who makes money, because that means anytime the roof leaks at the church, the pastor’s coming to you. So freedom means actually everyone around you having money. That’s what real wealth means. It means not just a guarantee for you that you’re doing fine, but like I’m in a community and I can walk outside knowing that everyone has access to what they need and can actually pitch in for our disposable discretionary ventures. Right?

So that’s how a federal job guarantee secures freedom for even people who have jobs in the private sector. So it’s not just that the private sector, it doesn’t absorb stigmatize people at fair wages and conditions and you know, a lot of stigmatized people are Black. So it doesn’t absorb Black people at fair wages and conditions. But even if you happen to like luck into a good job in the private sector, if everyone around you, doesn’t, like, you’re not free. You can’t be open. Every interaction you have is determined by the fact that they are struggling and you’re not and that means nobody in that interaction is free.

Grumbine (00:11:06):

Absolutely. So let me bring it back on that for a second. We go back to FDR with the concept of a right to a job and you know, his Second Bill of Rights, and we can go even further back to various tactics that we tried in this nation and you take into the sixties and seventies. You seen various moments where the idea of MLK came out with a minimum income and talked very strongly about a job guarantee.

Osei-Frimpong (00:11:37):

Yeah, he said it in clear words, in a speech was a “Showdown For Nonviolence.” Everyone should go check out that speech “Showdown For Nonviolence.” He’s clear as day about the need for a federal job guarantee and an economic bill of rights.

Grumbine (00:11:50):

Absolutely. I guess that’s the question here. African Americans were promised 40 acres and a mule coming out of slavery. They were promised that, and they were not given that. And that bit of generational wealth that was deprived of the African American community has been exacerbated every step along the way, every time, you know, we’ve talked about, I believe Keeanga in her recent book that she put out talking about red lining and the post red lining era with predatory inclusion.

I mean, every step along the way, people have made money on the back of Black people in this country, but they have been treated as a second class citizen and it’s kind of like if we gave everybody a job guarantee there wouldn’t be anybody down below us that we could just kind of look down our nose at and feel an inch better, you know, above the pig slop.

And you see the resistance to these sorts of things, you can see it through the Trump administration, you can see it through the entire nationalist movement, this alt right movement. But you also see it in a soft fashion in the Democratic Party even. You see it all over the place, this inherent deep seated fear and loathing that prevents such an incredibly important life saving and life changing and altering bill to even be properly talked about. Help me understand what it’s like as an African American to see every time there’s a spike in unemployment, the absolute shift is huge in the Black community.

It’s unbelievable. It’s always worse. COVID-19 hit Black America way worse than it hit white America. And it always hit the poor. It seems to be that as long as they can keep these kinds of programs out of the hands, that they can have an underclass that they can kind of point to, to make themselves feel better, or is it more insidious than that? What do you think is the rationale behind that?

Osei-Frimpong (00:13:55):

Well, I mean, there’s a lot going on, right? So I think one, there are a good number of white people who think that if Black people have power, they will be like white people and that terrifies them because they know how awful we make white people. So they’re scared that we’re going to be like you to you. That’s not something they want to open up the possibility with. So there’s that but there’s also the basic notion that you need some sort of economic security if you’re going to be politically independent, right?

You need an economic security if you’re going to be politically independent and that’s what the 40 acres and a mule was fundamentally about. You can’t be functioning as a free person in a democracy unless you have economic security and stability and in a market based democracy, disposable income, right? So it can’t just be a minimum or living. You need disposable. I think there should be a federal job guarantee. I could list 300 projects that the wealthy just can pay for it, but everyone else is priced out of like elder care.

And those jobs should just start at $22 an hour, right? So with that, you don’t even need a minimum wage cause everyone has a public option for employment that starts at $22 an hour. And I got that number because of wages actually stuck with productivity from 73 on we’d be at $22 an hour, but there was a big spike. There was productivity shot up and wages stayed flat and so we’re not.

I think there should be a federal public option for a job at $22 an hour, doing stuff that the market doesn’t actually provide for everyone like ripping out pipes in Flint, or, you know, there’s a hookworm epidemic in the rural South because of septic systems that get busted and it takes $12,000 to get a new septic system and people don’t have that kind of money laying around. So like people are getting hookworms.

So there are all these public works projects that need to be done — broadband. I’d like to read to seniors and getting class sizes down to like six. We could do all sorts of public works if we actually wanted to put people to work, making our citizens strong and our nation strong, but we don’t want to do wellness checks, especially in times like, COVID-19. I bet you there are people dying and nobody knows.

Grumbine (00:16:02):

Yeah.

Osei-Frimpong (00:16:02):

Cause we don’t do wellness checks, not really, and there’s no actual system in it. So people are dying and nobody knows and then when they’re dying, they’re also taking their cultural memories with them. If I were king of the world, what I would have is every time you hit 70, if you make it to 70, a three person videography team knocks on your door and you get three hours of a professional video, you get twice, they come once, and then they come the next week to get another three hours — where you just get to say your side of the story.

Then we put that in the National Congress. We tape all of that and just have it in the Library of Congress. So every American who makes it to 70 gets to just like talk and just walk us through the decades. “What were you doing in the sixties? What were you doing in the seventies? What were you doing in the eighties? What were you doing in the nineties?”

And that would be a great archive for our national cultural infrastructure and it would be searchable and I think it would just be a wonderful cultural artifact and, you know, it would actually fix history since the history is disproportionally told by people who have means to actually write their own autobiographies and get them published and I got this idea by this book, “They Were Her Property” and book came out two years ago by a woman who’s based out of Berkeley and it was based on the oral history project from the WPA.

Grumbine (00:17:22):

Wow.

Osei-Frimpong (00:17:23):

Right? So what we knew about kind of Southern History was always, especially Southern Women’s History was always by like these elite women who wrote in their diaries so the diaries were the archive; but because of this WPA program, they talked to these women’s maids and nannies and just working class people and it turns out that some of these women were telling stories about themselves that weren’t quite true.

And so you got a like a working class archive of people who, without the WPA program, we would have never known and we would have taken Scarlett O’Hara’s word for it. And it turns out that she wasn’t honestly being the most self-reflective and self-transparent person about her commitments. But like once you talk to her nanny and talk to her wet nurse, you talked to all these other people who wouldn’t have been able to pay for videographers themselves and pay for archivists themselves.

But because it was a government program that provided that archive, we got a very good book and a very good kind of picture of what life was like for, you know, the other side, the working side and the Black side of the American South and not just these elite white women’s journals. And I think that would be a great federal job guarantee job, right? So you need economic security in order to have political independence and we see this now.

I don’t know how much work people do in nonprofits or work people do in social services. Oh, just political organizing in general, you see that everyone’s scared of losing their job. That’s why they don’t do courageous things or say courageous things. They are scared of losing their job. So you can’t be free when the only people who can talk are independently wealthy and the only people who aren’t scared of losing their jobs.

And I don’t think it’s an accident that, for example, when we founded this nation, we really only made citizens out of the independently wealthy and then the landed gentry and independent professionals, right? So you either were an independent professional, or you had land that was handed to you from your family and you just made money off of that; and those are the people who ran this nation. Those are the people who were in Congress at the founding of this nation.

And if you look at the Congress right now, except for like, I don’t know, Ocasio-Cortez, and a handful of others, you pretty much have the independently wealthy and landed gentry and people who can be independent professionals, because those are the only people who could take off six months to run for Congress right? Or run for state senator. So the class makeup of our US Congress hasn’t changed because we don’t have the economic security in place institutionalized to secure our political independence as a democracy.

So in a well-ordered world, everyone should be able to vie for Congress, but you can’t vie for Congress when you don’t know if you have a job if you lose the election. You can’t vie for a Senate seat if it takes a quarter million dollars to run for a state senate seat. But you also can’t do it if you have to quit your job and you still have bills coming in every month, right? So what does it take? And there are other kind of rights-based issues that don’t get talked about. For example, legal care, we’re a nation of laws, but who has access to a lawyer?

Grumbine (00:20:33):

Amen.

Osei-Frimpong (00:20:36):

There’s a great article in the Intercept where there’s an interview with Peter Thiel who had just got finished backing Hulk Hogan against Gawker, right? And so Peter Thiel is an internet billionaire. He one of the creators of PayPal and he backed Hulk Hogan against Gawker because he had an axe to grind against Gawker and they ended up taking out Gawker, the news site, but he backed Hulk Hogan and he said, “Look, Hulk Hogan is just a single digit millionaire. If you are a single digit millionaire, you don’t have real access to the legal system. So I had to, you know, back Hulk Hogan’s legal fees so he could actually be a rights bearing citizen.”

Grumbine (00:21:15):

Wow.

Osei-Frimpong (00:21:16):

So if Peter Thiel, a billionaire is telling you that single digit millionaires aren’t real citizens and if you’re just a single digit millionaire, you’re pretty much food chum. That means like, what is everybody else? Right? So he’s pretty much admitting that he can do pretty much anything he wants to anybody who’s not a single digit millionaire because in a nation of laws, like if you don’t have access to a lawyer you’re not really free, which means we need some sort of legal insurance or legal care on the model of single payer healthcare so that you can actually press your rights because the courts are where a lot of this has worked out.

And if you don’t have access to a lawyer or you have to kind of trick a lawyer or convince a lawyer to take your case on contingency, based on their assessment of risk, you’re not really free because you only have rights insofar as you can kind of convince a lawyer that you’re a good risk. So you’re up to they’re like actuarial calculation. Your rights depend on their actuarial calculation. Or we let the market decide who gets legal representation.

So your rights are actually just a market dispensation. It’s like everything else that’s controlled by the market and so it’s asymmetrically distributed. So not everyone has rights. Only people who can afford lawyers do so they can sue other people who can afford lawyers but if you can’t afford a lawyer or you can’t wheedle one into taking your case, you’re just kind of chum and this is why we don’t have real sexual harassment laws, or why like employment law is kind of a joke. So we need some sort of legal care.

If we’re serious about guaranteeing people’s rights, we need some sort of legal care and not just legalese or legal aid cause that’s pro bono. That’s still, depending on someone else’s charity and your rights are not rights if dependent on someone else’s charity. Patrick Henry says this in a great piece he wrote called “The Great Injustice” where he just lays out the case. No, the rights are rights.

They can’t be like something that the church gives to you based on alms and someone’s charity. No, you need to be able to secure them. You need to know that you have them and not have to depend on some lawyer’s willingness to take your case pro bono, because maybe they feel either charitable or they’ve decided that you might be a good bet. I don’t want to have to be someone’s good bet. I want to have rights.

Grumbine (00:23:38):

Yeah. I want to raise that up cause you know, you have a guy like Philando Castile who is a legally licensed guy who has a concealed carry and every one of these folks that flooded the Wisconsin or Michigan state house, not one of them had any fear whatsoever they were going to get shot. But you got a guy like Philando Castile who was just blown away by a cop right there in his car.

Osei-Frimpong (00:24:03):

When he said, “I have a gun in my glove box. That’s also where my license and registration is. I’m going to just show you the gun permit and I’m going to show you my license. Don’t shoot me,” and then they shot him.

Grumbine (00:24:17):

Well, every step along the way, I’m blown away by this because not only the access to equal rights in terms of economic rights, which I think are foundational to all of the other rights, but you have these basic things. Think about what it would be like. You’re a cop and you’ve got some dude walking down the street dressed to kill, and he’s a white guy and he’s got the slick cocky hair, the whole enchilada. They don’t even think twice about it.

Now this is a guy who just sat there and built the banking system and literally killed thousands of people with austerity or whatever but they don’t even think about it. But you’ve got some guy like George Floyd who used a $20 counterfeit bill. Maybe he knew, maybe he didn’t know. It doesn’t even matter and the point is you’ve got to almost be perfect to have access to life. Forget legal rights just to stay alive.

Osei-Frimpong (00:25:10):

Yeah. That’s no way to live. That’s no way to be free. You have to be perfect. You can’t take chances in America. You can’t take a risk without worrying about getting shot and there’s so many horrifying aspects of the Philando Castile story, but there’s a piece by a guy named Kwame Holmes who did some research and found out usually when there’s a dead body in your neighborhood, housing values go down when there’s a homicide. I mean, it makes sense when there’s a homicide in your neighborhood, housing values go down.

However, in this neighborhood, it was kind of a white flight suburb he was passing through. I want to say Falcon Heights and it was a white flight suburb that was trying to make a name for itself. When the murder hit, housing values actually went up because it was a cop shooting a Black guy, right? So like, it’s actually good for your housing values if, from time to time, you let the world and the market know that we shoot Negroes here.

Like that’s the housing market and so like the rational actor will be like, “Well, it’s good for our housing value that this place is known to not be good for a Black group to go into.” So what does it mean that the market can do that to people? The market matters that much in people’s lives that it could profit from a police shooting of a Black guy’s death. So that’s a piece by Kwame Holmes that the word “necrocapitalism” is in the title, but Kwame Holmes.

Grumbine (00:26:34):

I have to look it up.

Osei-Frimpong (00:26:36):

Horrifying, but like the market signals that our cops shoot Black people is actually good for the homeowners in that neighborhood and that’s what we’re working against in this America. Right? We talked about vulnerability to police death just being one form of a generalized vulnerability that Black people face.

When you talk about morbidity rates, we don’t live that long, right? So like mortality rates, incarceration rates, homelessness rates, people are always surprised about how Black the homeless population is an urban centers. I want to say 40% in LA where Black people are only 8% of the population.

Grumbine (00:27:12):

Wow.

Osei-Frimpong (00:27:14):

So morbidity and mortality, homelessness, joblessness, and you know, incarceration, we’re targeted population. We’re just vulnerable. And so the vulnerability to police death is just one form of vulnerability. And the opposite of vulnerability is, you know, you got to defund the police because that’s a task that’s come out of strike breakers and slave catchers.

So that’s not big enough lead to economic justice or racial justice or labor justice. But also you need to think about what it looks like to democratize power and how democratizing power is the key to public safety. And in the same way that if you have the urban center and you want to keep it safe, you can hire a lot of police or you could do things to increase traffic because where there’s more like people walking around, there’s actually less crime.

Grumbine (00:28:06):

No kidding?

Osei-Frimpong (00:28:06):

So instead of having like secluded streets with a dicey number of people walking through, if there’s a lot of foot traffic around, there’s less petty crime. So like you need to empower people and think about safety through those kinds of mechanisms, as opposed to police. And one way to empower people is give them good jobs, right? So Alton Sterling died from police violence cause he was selling CDs out of his car at midnight.

And by the time you’re selling CDs out of your car, you don’t have access to a $22 an hour job where you could save up capital and like have a nice studio and get like money for marketing and distribution and then like quit that job, try your music business, and when that fails, go back to that job like a real entrepreneur should be able to. So like Alton Sterling died just because he was excessively vulnerable that as a part of being Black.

The list goes on of people who just died from the quality of economic vulnerability. Eric Garner died selling loose cigarettes, right? So like that’s what happens when you don’t have guaranteed access to a $22 an hour job and the only job you can get. It’s important that the federal job guarantees are actually good jobs because right now we’ve underpaid Black people in the labor market for so long. And it’s so many different sectors and jobs that like, it’s kind of taken the shine off of jobs if you can only get $9 an hour living in a city.

Like why even work in the above market, right? So we need to normalize good jobs. The way that you normalize good jobs is what the federal job guarantee as a matter of right and when they did it in India, it actually increased private sector employment because you have like a better public infrastructure for private sectors to do business and it made the private sector make working for them a better experience and more people went to the private sector.

There’s so many ancillary goods that come out of having a federal job guarantee that disproportionately help Black people, especially if it’s a good job at a good wage that will make the private market actually treat Black people like whole people.

Grumbine (00:30:08):

Darrick Hamilton has been advancing something called “Baby Bonds” for some time now. And one of the biggest things here is that we’re not dealing in a race where everybody started at the starting line at the same time and was given the same set of shoes and the same water and the same running shorts or whatever. We weren’t equipped the same. So Darrick, his idea of “Baby Bonds” seems to attack the generational wealth issue, but this comes back to another point which Sandy Darity has spoken about quite frequently, which is reparations; and I know Bernie Sanders was hit pretty hard for being silent on this.

Osei-Frimpong (00:30:48):

Yeah, that was probably the best thing that he could have done for the reparations movement, because that was the only way everyone else could get to the left of him; and they didn’t call them reparations either, but they would actually say the word.

Grumbine (00:30:58):

Right.

Osei-Frimpong (00:31:00):

Bernie being silent made everyone else try to like be relevant by talking about something.

Grumbine (00:31:06):

Right. Well, let me ask you this, that Sandy is very adamant that reparations is far more than a cash payment and the idea of, yes, we need cash, but you can imagine let’s put it this way. I can imagine those guys that were like down in Charlotte back when they plowed through a crowd of people.

I can imagine those kinds of guys say, “Well, you got your $50,000 reparations or $200,000 reparations. Why aren’t you perfect? Why aren’t you this? Why aren’t you that?” And then flip this thing around, and they’ve weaponized reparations completely bastardizing it, not realizing that money is but one small aspect of repairing the damage that has been done going back forever.

Osei-Frimpong (00:31:56):

Right. So when I talk about reparations, I think of the cash payment as just one aspect. I think of it as earnest money, right? So when you buy a house, and you’re looking at a house, you put down — what is it 3% — as earnest money so that the person who’s selling the house will take it off the market while you spend a few weeks talking to the bank and trying to get the mortgage together, right? So you buy the house.

You say, “I like the house, but I need to get an inspection. I need to go to the bank. I need about a month to get my finances right and then like, I’ll be able to cut you a check for the, you know, $200,000 or whatever for the house.” But you have to put down a small percentage of earnest money so that the person who is selling the house knows that you’re serious about buying it. And they’re not going to take the house off the market for a month in vain, right?

And the cash operations is kind of like the earnest money because it shows that white people are serious, right? Because the history of trusting white people in the Americas, the record’s not good, right? So it would almost be naive to think that any sort of reparations is serious because in a pinch, white people tend to white in a way that’s not particularly good for Black communities or Native American communities or Chinese communities or Japanese communities during World War II.

So like we need some sort of surety that this isn’t like that. Like this isn’t some sort of game where you give us quote, unquote “reparations” but then change all of the other structures of the game so that we lose. I tell people that it’s one thing if America is a big poker game and they don’t let you in. So that’s one justice. I need to be able to sit down, I need to be invited to the table and I need the ante to be able to play.

It’s another thing, when you get into the game, you got by some circumstance, you got the ante and you could actually play, but then you find out all of the other players are in cahoots against you. And that’s the situation of Black people, vis-a-vis reparations. What if we find out that like, “Okay, we now have money,” but then white people clan up and pass a bunch of like non anti-trust laws?

And so we’re locked out of all of the industries as they are. So like reparations needs to be also like corporate board seats in standing coal, oil, or like guaranteed profits and shares that go right to Black institutions of like foundational industries, like tomatoes and potatoes so that we don’t get locked out when white people get nervous and Black people being self-determining.

Intermission (00:34:57):

You are listening to Macro N Cheese, a podcast brought to you by Real Progressives, a nonprofit organization dedicated to teaching the masses about MMT, or Modern Monetary Theory. Please help our efforts and become a monthly donor at PayPal or Patreon. Like and follow our pages on Facebook and YouTube and follow us on Periscope, Twitter and Instagram.

Grumbine (00:35:47):

Like, for example, the marijuana industry of all things. Michelle Alexander, she is just fantastic and her new Jim Crow Laws (The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness is a book by Michelle Alexander) is a book that everybody should read. But the idea that the very people that profited off of jailing Black Americans through the drug war are now using laws to lock Black America out of selling marijuana legally and they are now taking that over. How does that even work like that?

Osei-Frimpong (00:36:18):

It’s fascinating for a few reasons. I mean, one of them is that it takes a half million dollars. If you want to open a dispensary in Boston, you need to show that you have a half million dollars in the bank capital. Who’s going to let me hold a half million dollars?

So I also saw a Washington Post article that said one out of every seven white families is worth a million dollars — and that’s one out of every seven — so like there is this money out there that people can make a few phone calls and get a half million dollars in one bank account long enough to show a screenshot to the licensing board. But for the most part, those people aren’t Black, right?

And it’s one out of every 45 Black people is worth a million dollars, but one out of every seven white people is worth a million dollars. A million dollars is both a lot of money and not a lot of money. I’m from California so that sounds to me like two houses. That’s one house in LA and like a property someplace else, right? So that’s both a lot of money and not a lot of money.

So it makes sense that one out of every seven white families is worth a million dollars but the idea that you need to show that you have a half million dollars of emergency capital in the bank before you can get a marijuana license is pretty much saying that like only stoner kids of bankers can get a marijuana license in Boston. I think in Colorado, it’s $250,000, but still these are ridiculous amounts of money. And then they’ll tell Black people, well, if you’re lucky and if you beg right, we might let you out of jail if you were caught selling marijuana.

Grumbine (00:37:54):

I gotta tell you this story. Back in 2002, I was getting ready to go through a divorce and I was finishing up a term paper for grad school and my now ex-wife came down to my office and said, “Just so you know, when you’re finished with this semester or whatever, we’ll be leaving or you’ll be leaving,” and so forth. So I had a brain melt. I had been sober for years. I decided, “Man, today’s my lucky day.” I’m going to go out there and I’m going to tie one on. And so I went out to a bar and I got completely destroyed and I acted like the big spender, was buying everybody drinks at the bar and sure enough, you know, not to be outdone, once the alcohol was flowing, I went ahead and bought pot.

I bought a bunch of pot about like two ounces right there on the scene. I don’t know. I had no idea why. I was drunk. So I drive up the road. Everybody said, “Hey man, you shouldn’t drive away.” “I’m just going up the road. I’ll be back.” You know? So I get up to 7-11, I’m going to buy cigarettes and the guy who’s at the counter is looking at me. He smelled me a mile away and there’s a cop over there, stirring his coffee and I said, “Do you think he knows I’m drunk?” and he goes, “Well, if he didn’t before, I’m pretty sure he does now.”

So this cop comes up and he starts giving me a back rub right there at the counter. And he’s like, “Look, it’s December 14th. I think that, you know, this is going to be your Christmas gift. Go on out there and make a phone call and we’ll pretend this never happened.” Well, so the only person I’m going to call is my soon to be ex-wife who’s already ready to leave me and I’m not really looking forward to being left and I’m certainly not going to call her at two, three in the morning cause I’m drunk.

So I decided that I’m going to wait this cop out and I fall asleep head first into the bricks right there where the phone was and I get up, Oh, I better leave. So I get in my car and the guy was sitting there waiting for me. He wasn’t going nowhere until I went somewhere. And as soon as I got in the car and pulled out, you hear that boom. And there I am two ounces of pot. They find all of the pot. I’m drunk. My tags are to everything in the world is wrong.

Osei-Frimpong (00:40:17):

Two ounces? That’s distribution. People get . . .

Grumbine (00:40:18):

Oh, buddy, wait, you ain’t heard nothing yet, right? Now I had been sober for eight years. There was no reason in the world that I was going to be drunk. It was the one night you just shouldn’t have done it. Well, I tell you the story because after they did a cavity check on me and after they literally took everything out of my car, etc. I get in the jail and I’m thrown into a holding tank; and there are three young Black kids in there. I mean, young.

I mean, they might be old enough to be in jail with me, but not old enough for any other thing. Right. And they didn’t look harmful. They didn’t look scary. They were short. They were skinny and they were like, “Hey, what are you in here for man?” I’m like, “A lot of pot, man. So what are you in here for?” and they’re like, “We got caught with a joint.” “Really?” So I get taken to the commissioner shortly thereafter and he says, “Listen, looks here that you work at Bell Atlantic. That’s a damn good company.”

This is a Black man. This is a Black commissioner, that’s hearing me, right? “It looks like you’re a good upstanding member of the community. You’ve got a family, blah, blah, blah. Don’t make me regret this,” and he let me go on my own recognizance. Now I did have to go to court. I am facing heavy charges, two ounces. That’s a of weed, right? So I go to court and I do all this stuff but I come back to the jail cell, holding tank, waiting for my brother to come pick me up.

And these kids are going to be held for three weeks until their hearing — for one joint. Three weeks, they’re going to be held for their hearing and I am being released right then and there and I had two ounces. Now, mind you, there’s a bunch more to that story. I ended up getting off with misdemeanor possession charge. They threw out everything else and I went to a rehab and even got that down, right? So that was the story of this guy through the criminal justice system and you know, for my sake. Okay, thank God. Right?

But for their sake? It never left me. That experience changed me on more than one way, right? I mean, it changed me incredibly. And I wonder, I mean, that’s just a small microcosm, but you duplicate that a million times over again or more, and I know how much money it costs me to go through that process. I know how many jobs it costs me after I left Verizon because you know, Bell Atlantic turned into a bunch of things. So I know what it was like when I tried to find a job with that record, with just a misdemeanor possession charge, not a big brand dealer charge or any of that stuff, right?

Osei-Frimpong (00:42:54):

Right. It’s not a negligible amount of pot.

Grumbine (00:42:59):

No, and literally they knocked it down to just a simple misdemeanor. Now mind you, I didn’t even remember buying it to be perfectly frank. I mean, it was like one of those things where I was incredibly inebriated, but that’s not even the point. The point is, is that the difference in how I was treated and I thought it was the worst thing ever. I was terrified. It was awful. I couldn’t believe I was in jail. I couldn’t believe that I had to go to court and then when Verizon, let me go in the great financial crisis, I tried to get another job and all of a sudden they did background checks.

I didn’t have to worry about background checks at Verizon. I was already an employee, but now outside of the sacred realm of Verizon, everybody was wondering what the hell I was. And I couldn’t find work and the fundamental driver behind so much of my activism happened from that period of time; but it speaks to a microcosm of what happens in the African American community. If that happens so many times, it’s no wonder you can’t gain any generational wealth. It’s no wonder you can’t move up the food chain because just my little misdemeanor charge after all the finagling.

Osei-Frimpong (00:44:05):

It cost a half million dollars over 15 years. Yeah.

Grumbine (00:44:07):

It destroyed my career. It destroyed any chance of a real career and so I can only imagine how cut out of the regular economy, cut out of prosperity, cut out of pursuing the “American Dream,” whatever that is. Fill me in, man. Fill in the blanks here, because that to me has just been a huge gaping wound in my life that I haven’t been able to shake the impact of it.

Osei-Frimpong (00:44:35):

Well, I want to say a few things. One, you hit the trifecta here. I always say that, you know, it’s hard to radicalize people who’ve never been dumped, fired or jailed. But in like one night, you kind of did it all.

Grumbine (00:44:50):

I went yard, man! [laughter]

Osei-Frimpong (00:44:50):

Cause you think unless you’ve been dumped, fired or jailed all for kind of doing like regular things, you kind of think that the world is kind of organized for the most part pretty well, but once those happen, you’re like, “Wait a minute.” You’re betrayed by like systems, entire systems, and then the systems that told me these systems are legitimate.

Grumbine (00:45:11):

Yep.

Osei-Frimpong (00:45:12):

So I’m a fan of people being dumped, fired and jailed at least once and I’m a little bit suspicious of people who have never been any of those.

Grumbine (00:45:20):

Yeah.

Osei-Frimpong (00:45:23):

We all know those people who exist. I don’t want them next to me in a fight though.

Grumbine (00:45:30):

It’s funny because I have huge amount of student debt hanging over my head. I was able to turn my life around, so to speak. After that many people wouldn’t have gotten that opportunity to “turn their life around,” but I did, and I took it for everything it was worth to my best of my ability and got two masters degrees and started off going into a PhD in organizational change and leadership. And I ended up dropping out of that when I went through my second divorce. I’ve got a track record, you know, in that respect.

Osei-Frimpong (00:46:04):

I don’t understand how you could have any cash after two divorces.

Grumbine (00:46:07):

It’s horrible. I’m not even going to go into it. Let’s just say, it’s not good.

Osei-Frimpong (00:46:11):

You need a federal job guarantee cause . . . [inaudible]

Grumbine (00:46:16):

Exactly. But you see economic despair, economic insecurity, food insecurity, all these things that come from this. It’s literally like putting a drop of ink in water and it polluting the whole thing. That’s how bad this is; and you don’t realize it in the moment until you start seeing all the tentacles and all the corollaries and tributaries that come from this one bad moment.

This one bad moment set the stage for a million other bad moments. And if you’re living in fear of that constantly to begin with, I can only imagine being cut out of the normal economy than being forced like you were saying, you know, if you’re selling loose cigarettes or if you’re selling CDs out of your trunk or whatever you’re already out of the regular economy. What does it feel like? What is that all about? You know, what is that?

Osei-Frimpong (00:47:07):

I felt depressed because I went to a fancy undergrad and I speak moderately well. So I felt the pressure of, if I do everything perfectly, I could be someone legitimate. I could be a judge. I could be a Congress person, but I would have to do everything perfectly and make everyone comfortable all of the time. And that was just not freedom. Like that’s not freedom. So like that kind of fragility in your life that all of your aspirations and your will can just be overwhelmed by someone else’s anxiety if you take up too much space.

I don’t know what would happen if I were like 6’3″, 6’4″, and big, and I’d have to like, not take up any space in a job interview and like it’s really something being conceived as a threat throughout your teens and twenties, no matter what you do. But I would have to be so perfect all of the time and I could make it. But what kind of life would that mean? I’d always be very anxious about like making one mistake before I was perfectly settled at a good age.

But what happened was I just gave up, and I did the academic approach to Black guys who give up looking for jobs and just work in the underground economy do. I only worked jobs where it would be impossible to fire me because I was so overqualified. You know, I’ve had every job as a cashier, all the places and, you know, met my wife at a bookstore and when I was working at a bookstore; and so I did that for awhile.

I did that for forever and people are still a little bit suspicious about my possibility of getting a job once I’m done. The good news is that my academic work is actually pretty interesting. So I’m not too worried about getting a job, but like they’re horrified about the things I say in public, because they’re terrified for me on the job market.

Grumbine (00:48:55):

Yes.

Osei-Frimpong (00:48:56):

That’s an awful way to be in life. Like, are you really free? So I have a formal right to free speech, but if I’m so tethered into civil society and so vulnerable in civil society that like I have a formal right to free speech, but it’s going to jeopardize every market-based opportunity I could have going forward then do I really have a right to free speech if I can’t exercise it? I don’t think so. I don’t think so.

So I emancipated myself by just changing my aspirations for my life. The most important thing for me is to be free and the struggle for justice, for the community, as opposed to, you know, some sort of individual come up. So I live in Athens, Georgia. I don’t live in California. I grew up in California. Then I was priced out of California, so I can’t go back. I’d love to live in Oakland. I like Oakland a lot, but I can’t afford to move back. So I’m in Athens, Georgia, and that’s just the life I live because if I’m going to live out there where everything costs and yet my place in civil society is so vulnerable, like I wouldn’t be free.

I’d be hemmed in. I wouldn’t be able to say what I want as the Funky Academic, which everyone should check out if you like anything that I do or that I’m saying on this podcast, go to thefunkyacademic.com, check out the videos there and maybe kick in $5, $15 or $50 a month because depending on who you talk to, I’m making myself down white unemployable but speaking as honestly as I am about, you know, what we need the economic conditions for Black freedom.

So I decided to live my life free, but that meant giving up a lot of economic opportunities because our economy is based on being okay with securing systems of injustice. And I’m not okay with that; and a Black guy who’s not okay with that is even more of a threat because what if I get other Black people who are not okay with that speaking loudly, that doesn’t make the bosses feel comfortable. So there’s a great book called “Edge Work” written by Wendy Brown. In the third chapter, she writes on neoliberalism and she says, “It’s not obvious whether you can both climb the ladder of success while reorganizing the ladder.”

Grumbine (00:50:55):

Right.

Osei-Frimpong (00:50:55):

Right? So people want to have it both ways. They want to both be successful and be the impetus for organizational change and justice, and you can’t do that. And Black people know they can’t do that cause we watch a lot of our leaders die broke, right? Broke. Malcolm X broke. Rosa Parks broke. And for decades, at least she made it for decades, but she died broke. Hosea Williams.

Like all these Black leaders, you know, they died broke and so that’s just the price of justice, but it shouldn’t be, and it doesn’t have to be if we secure an economy as a part of political freedom; and we understand that as one of the necessary conditions and preconditions of political freedom we are going to secure. You can run for office and lose and you’re going to get a job once you lost your election.

And you’re going to platform and tick off your boss with your platform and you can get a job knowing that you ticked off your boss with your platform; and we’re still going to secure you a job afterwards. That’s what freedom looks like.

Grumbine (00:51:57):

Well, let me ask you to take us into the final runway here on this. With the situation we have in the streets today . . .

Osei-Frimpong (00:52:03):

Right.

Grumbine (00:52:03):

We’ve seen moments where we’ve had some energy, the original real push with Black Lives Matter with Trayvon Martin and we’ve seen so many of them. It’s terrible, but it’s like the list of names is just so long. I wish I could commit them all to memory.

Osei-Frimpong (00:52:23):

Every few years, not even every few years, I feel like every other year there’s like some awful situation where a Black guy shot in the back and it’s news. Cause like, Black guys are shot often, but news that a Black guy shot in the back by a cop and I remember first started paying attention when I was in high school but when I really realized it was a problem, I was like 22 and this kid from Cincinnati was like shot in the back, like running away and it was just ridiculous.

At first I didn’t even know if Minneapolis would actually become a thing, but I feel like it was a confluence of a few events that actually made this happen but we have to understand we’re fighting institutions and institutions are organized and are built to withstand flare ups. Right? They’re built to withstand flare ups. So this is a flare up. So how do you institutionalize a flare up? And I was talking to my buddy, Tommy Curry about this. He got a great book called “The Man-Not.” If you’re interested in books, go check it out.

And he was saying like, “One of the successes of the Black power movement was that it changed the curriculum.” It wasn’t just a protest because the universities were organized to sustain protest, but it changed the curriculum. You had budget items for Black Studies Departments, African American Studies Departments and that changed requirements and now students had to take one. It changed the life of the university by becoming part of the institution. So for this uprising, not to just be a flare up, we need to institutionalize the change in America. We need to change curriculums. We need a concrete ask.

That’s why one reason I’m kind of a fan of the defund the police department. Because right now in my town, in Athens, Georgia, some 45% of the County budget goes to police in some form, either the sheriff or the jail. So I think everyone should check out their town and see how much of the budget goes to law enforcement. So we’re pretty much throwing law enforcement out of all of these problems that we just got too lazy or too unimaginative to solve in a way that they’re not qualified for.

So we send them to jail — the people we find uncomfortable. But there are lots of ways to live in a police state. One of them is by living through an ever lasting fear of the cops. The other way to live in a police state and one of the other ways of living in a police state is having the police take 45% of all of your tax dollars. So even if you’re not living in fear of the cops, the fact that the cops have so much of the public treasure means that we are de facto a police state because that’s where all of our treasure goes. So we need to think about different ways of being a police state and if all of your treasure goes to the police, yeah, you’re a police state.

Because you don’t have public parks and music lessons for your kids because all that money goes to the police. The police sucks all the air out of your budget. So you are de facto a police state even if you don’t feel like you’re in one. I think all your listeners should go check their municipal budget and find out what percentage goes to law enforcement for their new toys and what that means on a political [inaudible]. I do want to talk about the looting one, because if I bet a fantastic take on the looting, and I haven’t seen it since.

We all assume that there’s property damage and we care so much about property in America, not other rights, but property rights as if like they’re not just rights, like all the other rights, but we care a lot about property rights. So people are talking about looting as if like it’s the destruction of property, but it’s not the destruction of property. It’s the distribution of property through an untoward means. Right?

So there was a story about the DJs and the reason we have hip hop right now, because a lot of DJs came out in New York, but the reason why the DJs got the equipment and we went from like one DJ per like eight miles to like 16 DJs is because of the riots during the seventies where all of these electronic stores got looted and those goods were then distributed to like, you know, kids pretty much and young people who then became DJs because they actually had the equipment.

So when you see a Target looted, maybe you should think about like now someone’s got like a nice camera, right? So you’re gonna see like photography businesses. People have like laptops now and high end equipment and so it’s, it’s a distribution of capital, of investment capital, that is unsanctioned by law and is informal and maybe not ideal, but maybe the other distribution of capital was really starving out all of these would-be entrepreneurs.

Grumbine (00:57:01):

I betcha there’s a nice multiplier effect on that.

Osei-Frimpong (00:57:03):

Yeah. So now, like there’s a nice camera. Like the, now this guy can have a little wedding photo business or whatever, and it’s kind of concentrated. So a lot of people now have a shipment of goods that they could use. So it’s not goods being destroyed. It’s goods being redistributed. So they’re not just sitting on Target’s shelf, which is, you know, Target is going to be insured by AIG anyway. AIG still exists, right?

Grumbine (00:57:29):

I think so.

Osei-Frimpong (00:57:29):

So it’s insured through AIG that’s going to get their fair share of bailout money. So we just, we distributed a lot of goods through the looting and we need to understand that that’s kind of what happened. It’s not the ideal distribution of goods.

I’d rather everyone get a good job so they can go in and buy it but I can’t get worked up over it because when I see someone walking out with a vacuum, that just means that their carpets are going to get cleaned. Like by the time you’re looting a vacuum, like you just need a vacuum, man. [laughter]

Grumbine (00:58:04):

I want to ask, I thought you were going down this path. And then you went into a totally different path than I would have ever dreamed, which is great, which is perfect actually, but the real question that I had is it seems like the point you were making that America’s obsessed with property rights. Okay. And the police are there not to protect and serve, but to protect private property.

Osei-Frimpong (00:58:28):

Right.

Grumbine (00:58:29):

And you think going back a few 24 hours that African Americans as slaves were once private property, and the way that this stinks to high heaven, you can go through this over and over again and at the end of the day, it’s like, they’re there to prevent people from taking their 40 acres and a mule, so to speak. What else can you say?

Osei-Frimpong (00:58:55):

Right. So there’s a great book by Robin Einhorn called “Taxation and Governance.” Anyway, you have to understand that when we designed the United States, the southerners didn’t care about democracy. They didn’t want London to abolish slavery in all of their colonies. Like the ramp up was about to happen, right?

So Britain at the time was slowly but surely abolishing slavery in the colonies and there was a Somerset verdict then the Edict of Dunmore more on all of these historical moments leading up to the Revolution of 1776 that made property insecure in so far as property was slaves for the American South. And you have to understand that we designed our constitution with property so enshrined and so important and to be guarded against because we’re living with the people who was actually terrified of their property, right?

So they were terrified of Black rebellion while also wanting to secure property rights. That’s why we worship property rights in a way that we don’t actually worship a plenitude of rights. This is actually my dissertation on the plenitude of rights because property rights are very important institutions of freedom, but they’re also just one variety of rights. We should care this much about voting rights, about the rights to vie for office, about legal rights, the rights to representation, economic rights, the economic security in order to be politically independent.

All of these rights are equally important and they can’t all be reduced to property, not anymore, not in an industrial economy. So we need to talk about our plenitude of rights with the same reverence as we do property. And my city went through a curfew about two weeks ago. It instituted a curfew because it was scared of the protests and when you institute a curfew, you’re just vacating people’s rights to go outside in a way that’s very, very worrisome.

But if we actually respected those rights like we respected property rights, we would have that conversation. But because we were terrified of our property actually attaining rights and obtaining guns to get us, we secured property rights and we’re kind of loosey goosey, about institutional interpersonal rights in a way that we shouldn’t be. We should be just as worried about voting rights.

We should be just as worried about civil rights as we are about property rights, because those two are institutions of freedom and we can’t play favorites. So property isn’t more important than all of our other rights. We just have been conned into thinking that it’s some [inaudible] right that out of which all of the rights can be justified in terms of — when it’s just like one right out of many, and all of them need to be balanced and modified to respect each other. So if you take away my voting rights and I take away your property rights by looting, you know, we have justice problems. We shouldn’t play favorites about which justice problem gets priority.

Grumbine (01:01:52):

I guess my final take and I want to see what your thoughts are on this is that instead of being as political people, as people fighting for democracy and fighting to change society in whatever fashion, your dissertation on rights, I think is exactly where everything that we do going forward needs to be focused because we see us dinking and dunking around these ideas about programs. And.

Osei-Frimpong (01:02:19):

Thank you, no, No program, no more programs, rights.

Grumbine (01:02:22):

Yes, citizen’s benefits, rights. You know, there is still no right to an education? There is no legal right to an education. This is one of those federalized 10th amendment type deals. There is still no legal right to an education and there’s so many things out there, the right to a job. This is where we need that federal job guarantee to be not just a program, but to be a right, to be a legal right. You don’t have to worry about it being taken away because it’s a right; and we need to get into a rights-based approach to revolution if you will.

Osei-Frimpong (01:02:57):

Yes, I, yes.

Grumbine (01:02:59):

So lay it out there, man. That is my whole mindset. So it sounds like we’re on the same page. So I’d love to hear your take on that.

Osei-Frimpong (01:03:06):

Look, there are a few things going on, right? So right now, as it stands, the sentimental left, what I call them thinks that you can win an are justified in winning based on like, you know, compassion and hoping people like pity you in the right way and do what’s nice. Whereas the right, you know, you got Rush Limbaugh on radio for four hours a day saying that you need freedom and this is what freedom entails — these rights.

And Sean Hannity comes in after him and he’s talking about rights for another four hours. And then you listen to Fox News and they’re going to talk about rights and freedom and dig not particularly deep cause I think I have deeper arguments, but they’re going to at least fight on that terrain. Whereas we’re fighting on the terrain of people’s feelings and that’s an inappropriate terrain because America is based on the idea that freedom is more important than life.

Give me liberty or give me death. So let’s actually dig down on what liberty entails. How free are you if you can’t apply for a job because of a record? Like how free are you if you can’t afford cash bail, if there is such a thing as cash bail? Like how free are you if you don’t have access to a lawyer and everyone you’re fighting does? You’re not, right?

And in an industrial economy, if you don’t have access to a job, you’re not going to compete with Bezos. So you can’t just like start up on your own without any capital. Capitalism without capital. You need a guaranteed job that’s actually like is enough to give you disposable income. So there’s this great guy by the name of Richard Dien Winfield. He’s actually running for US Senate.

Grumbine (01:04:39):

I know him.

Osei-Frimpong (01:04:40):

Yeah, he’s fantastic. He’s running for US Senate in Georgia, right? It’s gotta be a hard state to win. It’s hard to make [inaudible], but he wrote a book about the social bill of rights. It’s called “Democracy Unchained.” It just came out, I want to say, about two months ago and he lays out just a series of rights and the arguments for them. For legal care for all. For a federal job guarantee. Prisoners need to be able to vote.

We don’t alienate you from all of your rights just because you’re locked up. We don’t vacate your property rights and annul your marriage and decide that you don’t have all of your rights are gone just because you’re locked up, which means that like you should be able to actually vote in prison. And that would force candidates to campaign in prison. Having been locked up myself and you were locked up a little bit. Like a lot of people would profit from that experience.

A lot of politicians would profit from the experience of a night in a holding cell. What it’s like. So these people need to have a political voice. So yeah, we need felons who are living right now. They should be able to vote. If you can’t politically organize, I don’t know, a wing of felons, and their vote wins over your vote, then like you may be on the wrong side of the argument. Everyone should be able to vote. Everyone to be able to redress their politicians.

So he goes through a series of rights about just what we need to be free. He also draws a little bit of inspiration from FDR and the Second Bill of Rights, because it’s just where we need to go. We’re not free as long as we’re scared to be honest and still keep our job, which means we need a guaranteed job to pay our mortgage, right? So we need legal care. We need childcare because you’re not free if you’re also, I think a lot of parents finding out with schools closed, if you’re also chasing after a five-year-old.

You can’t be free, if you have to also take care of your parents. Elder care, right? Elder care is an enormous issue but if you have money, it’s not an issue for you. If you don’t have money, it’s sucks away your ability to work in the private sector and do your other job, because you’re always worried about getting your mom to her doctors appointments. There are a series of rights that we need in order for all of us to be free and we’d leave it up to the market to distribute these as privileges, but really eldercare shouldn’t be a privilege and it is a rather steep privilege.

I’ve heard anywhere from $4,000 a month to like $7,000 a month for elder care. So the only people who get to actually take care of their parents in style are those who are generally wealthy. Cause who could afford $4,000 a month for elder care? It’s ridiculous, but everyone gets old and everyone has parents who get old. So if we’re going to be free and free the next generation, I call these rights kind of age-appropriate social security.

We secure your education when you’re young and then we secure your job when you’re working age, and then we secure your retirement when you retire. And if you’re somehow disabled, we’ll secure your disability, but we need stuff, so we need you to work. We need you actually to produce stuff, but like we’ll secure you a job an a good wage, and that’s just social security, that’s age and ability appropriate and that’s how we should think about, I think a federal job guarantee and all of these other rights.

Grumbine (01:07:44):

I think you hit the home run ball there to close us out, man. So you kind of let us know how we could find you before with the Funky Academic. I really would like for people to be able to find you, because I think that if they watch and listen to you on YouTube and stuff, that they’re just going to be fascinated.

I’ve got a true bro crush on you and listening to the stuff you’ve been saying and reading the stuff that you’ve been saying has really spoken big time to me and I really appreciate you taking this time with me because I didn’t feel I had the platform to be able to say this stuff and I wanted to have somebody that could say this stuff in a way that would maybe open some people’s eyes and open some people’s hearts and ears to understanding what the lay of the land is and what some of the real solutions are, not these band-aids that keep getting thrown at us.

Osei-Frimpong (01:08:33):

And we need rights.

Grumbine (01:08:34):

And I think rights-based approach is the rock solid way of going, man and I just really appreciate your take. I really do. Thank you.

Osei-Frimpong (01:08:43):

Rights are simply what freedom looks like when it’s externalized. Rights are externalized freedom. So if you care about freedom and if you think this is about freedom, the rights-based approach is the way. That way, you’re not under the thumb of some charity whose donors’ ass you have to kiss or like the market so the hegemony and tyranny of the market. So you need rights and we need to talk about rights and fight on that terrain and not just cede the terrain of freedom and rights to the right.

So yeah, you can find me on funkyacademic.com. and I think honestly, Winfield’s book, “Democracy Unchained,” I think it’s the policy guide for the left. It could be written a little bit more friendly, so it’s a little bit dense, but he goes through the argument so systematically, about like what rights we need and how this all fits together and how this kind of unfolds so that we can have a family life where we actually like fulfill our family responsibilities.

We can to have a civil society life where we actually can be a productive member of civil society as an individual and do this in a way that also allows us to vie for political office and go to meetings and speak freely about the matters that concern the program of the whole of society without letting that jeopardize our family or jeopardize our jobs. So it’s a great book, “Democracy Unchained,” by Winfield and I think it should be the playbook for the left or the policy guide for the left and if you like what I’m saying, I think you should go to my website and check out funkyacademic.com.

Grumbine (01:10:10):

Awesome. Irami, I really appreciate your time. Folks, this was Steve Grumbine. Say goodbye, sir, because I really appreciate you. I hope you can come back soon.

Osei-Frimpong (01:10:20):

You got it. Take care, guys.

Grumbine (01:10:21):

All right. This is Steve with Macro N Cheese. Have a great day, everybody. We’re out of here.

Announcer [music] (01:10:31):

Macro N Cheese is produced by Andy Kennedy, descriptive writing by Virginia Cotts and promotional artwork by Mindy Donham. Macro N Cheese is publicly funded by our Real Progressives Patreon account. If you would like to donate to Macro N Cheese, please visit patreon.com/realprogressives.

funkyacademic.com

- “Necrocapitalism or the Value of Black Death” July 2017 by Kwame Holmes

- Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

- The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

- The Man-Not by Tommy J. Curry

- Patrick Henry: https://www.insearchofliberty.com/patrick-henry-democracy-individual-rights/