Originally posted on April 1, 2011 at the New Economic Perspectives blog.

Approximately a decade ago I wrote a paper with a similar title, announcing that forces were aligned to produce the perfect fiscal storm. What I was talking about was a budget crisis at the state and local government levels. I had recognized that the economy of the time was in a bubble, driven by what I perceived to be unsustainable deficit spending by the private sector—which had been spending more than its income since 1996. As we now know, I called it too soon—the private sector continued to spend more than its income until 2006. The economy then crashed—a casualty of the excesses.What I had not understood a decade ago was just how depraved Wall Street had become. It kept the debt bubble going through all sorts of lender fraud; we are now living with the aftermath.

Still, it is worthwhile to return to the “Goldilocks” period to see why economists and policymakers still get it wrong. As I noted in that earlier paper:

It is ironic that on June 29, 1999 the Wall Street Journal ran two long articles, one boasting that government surpluses would wipe out the national debt and add to national saving—and the other scratching its head wondering why private saving had gone negative. The caption to a graph showing personal saving and government deficits/surpluses proclaimed “As the government saves, people spend”. Almost no one at the time (or since!) recognized the necessary relation between these two that is implied by aggregate balance sheets. Since the economic slowdown that began at the end of 2000, the government balance sheet has reversed toward a deficit that reached 3.5% of GDP last quarter, while the private sector’s financial balance improved to a deficit of 1% of GDP. So long as the balance of payments deficit remains in the four-to-five percent of GDP range, a private sector surplus cannot be achieved until the federal budget’s deficit rises beyond 5% of GDP (as we’ll see in a moment, state and local government will continue to run aggregate surpluses, increasing the size of the necessary federal deficit).

[I]n recession the private sector normally runs a surplus of at least 3% of GDP; given our trade deficit, this implies the federal budget deficit will rise to 7% or more if a deep recession is in store. At that point, the Wall Street Journal will no doubt chastise: “As the people save, the government spends”, calling for a tighter fiscal stance to increase national saving!Turning to the international sphere, it should be noted that US Goldilocks growth was not unique in its character. [P]ublic sector balances in most of the OECD nations tightened considerably in the past decade–at least in part due to attempts to tighten budgets in line with the Washington Consensus (and for Euroland, in line with the dictates of Maastricht criteria). (Japan, of course, stands out as the glaring exception—it ran large budget surpluses at the end of the 1980s before collapsing into a prolonged recession that wiped out government revenue and resulted in a government deficit of nearly 9% of GDP.) Tighter public balances implied deterioration of private sector balances. Except for the case of nations that could run trade surpluses, the tighter fiscal stances around the world necessarily implied more fragile private sector balances. Indeed, Canada, the UK and Australia all achieved private sector deficits at some point near the beginning of the new millennium.

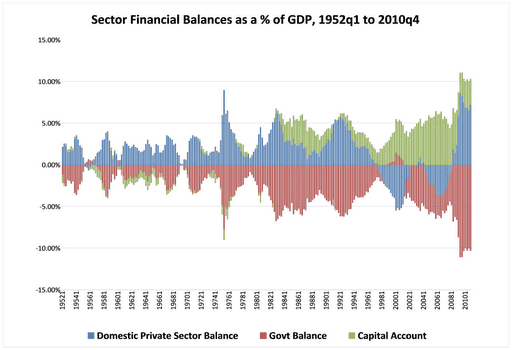

As we now know, my short-term projections were not too bad, but the medium-term projections were off. The Bush deficit did grow to 5% of GDP, helping the economy to recover. But then the private sector moved right back to huge deficits as lender fraud fueled a real estate boom as well as a consumption boom (financed by home equity loans). See the following chart (thanks to Scott Fullwiler):

This chart shows the “mirror image”: a government deficit from 1980 through to the Goldilocks years is the mirror image of the domestic private sector’s surplus plus our current account deficit (shown as a positive number because it reflects a positive capital account balance). During the Clinton years as the government budget moved to surplus, it was the private sector’s deficit that was the mirror image to the budget surplus plus the current account deficit. This mirror image is what the Wall Street Journal had failed to recognize—and what almost no one except MMT-ers and the Levy Economic Institute’s researchers understand. After the financial collapse, the domestic private sector moved sharply to a large surplus (which is what it normally does in recession), the current account deficit fell (as consumers bought fewer imports), and the budget deficit grew mostly because tax revenue collapsed as domestic sales and employment fell.

Unfortunately, just as policymakers learned the wrong lessons from the Clinton administration budget surpluses—thinking that the federal budget surpluses were great while they actually were just the flip side to the private sector’s deficit spending—they are now learning the wrong lessons from this crash. They’ve managed to convince themselves that it is all caused by government sector profligacy. Especially, spending on public sector workers.

For example, Wisconsin Governor Walker’s attack on workers has been taken on the pretext that state employee wages and pensions have driven the budget into deficit. We all know that is ridiculous. The reality is simple: Wall Street crashed the economy, crashed state revenues, and crashed workers’ pensions. Washington responded with a massive bail-out for Wall Street—perhaps $25 trillion worth. It gave a mere pittance to “Main Street” in its $1 trillion stimulus package. Since the recession manufactured on Wall Street cost the economy a lot more than that, Main Street is not on the road to recovery. No one is projecting that jobs will return for many more years. It is delusional to believe that economic recovery can really get underway until we have added 8 million jobs.

In other words, the fiscal storm that killed state budgets is the same fiscal storm that created federal budget deficits. You cannot lose about 8% of GDP (due to spending cuts by households, firms and governments) and over 8 million jobs without negatively impacting government budgets. Tax revenue has collapsed at an historic pace. State governments really do need to balance their budgets, and they really do need tax revenue to finance their spending or to service debt. The federal government, as the sovereign issuer of the currency is in a different situation. I will not go through the MMT approach to sovereign currency spending as all readers here are familiar with that. My point is that states really are facing a funding crisis. The federal government does not face a solvency constraint and it can always afford to buy anything for sale in dollars. Still, as we all know, Washington Beltway insiders have manufactured a fake budget crisis to serve political ends.

State spending cuts (or tax increases) will not restore their budgets. Just take a look at the results of austerity in Greece or the UK. Budget-cutting in a downturn does not reduce deficits significantly. The reason is obvious: austerity slows the economy and reduces tax revenue. Art Laffer’s supply siders were onto something, although they mostly got it the wrong way around. Yes, a booming economy will generate a movement toward balanced government budgets. They thought that tax cuts are always the answer to everything—cut tax rates and you get more tax revenue. I would not say that that never works, but it didn’t when Presidents Reagan and Bush tried it. However, if we get the Laffer Curve the right way around, we can use it to explain why austerity in a downturn just makes budget deficits worse.In truth, state budgets will not recover before the economy recovers. And state austerity will just make the economy worse.

So, as a Thatcher might say: TINA: there is no alternative–to federal government stimulus, that is. I realize that goes against the deficit hysteria in Washington. But it is the truth.

What kind of stimulus makes the most sense? I think we need another trillion dollars, minimum. This can be split equally between aid to the states and extension of the payroll tax holiday. The federal government should provide $500 billion in block grants to the states, on a per capita basis. On the condition that they stop attacking state workers. The funds would be used to replace lost tax revenue—to cover operating expenses (and where possible, to actually increase spending on priority projects). This program would continue until economic growth and job creation reaches established thresholds. Let us say 10 million more jobs or a measured unemployment rate of 4%.

The payroll tax holiday would also be expanded, with a moratorium on taxes for both workers and employers until those thresholds are reached. Why penalize job creation with an employment-killing payroll tax? Reward firms for providing jobs by giving them tax relief. Let workers keep more of their hard-earned pay. This is the quickest and best way to give significant tax relief to most Americans. In addition, we need to stop the attacks on unemployment compensation. To be sure, jobs should always be favored over unemployment compensation—but until we get the jobs we must extend the unemployment benefits. Cutting benefits will just prevent the jobs from coming back.

These measures are only a first step. We still have a lot of damage to repair—damage caused by Wall Street’s excesses. And we will need to reign-in and prosecute the fraudsters, otherwise they will blow up the economy again. Actually, they are already trying to do that—creating yet another commodities market speculative bubble. It is looking an awful lot like 2006 all over again. However this time, we are down by 8 million jobs and trillions of dollars of household wealth. Wall Street is bubbling up even as the economy as a whole is in the trenches. This bubble will not last long. It is going to crash. That will expose the huge accounting holes in the bank balance sheets. Wall Street will want another 25 trillion dollar bail out. This time, we’ve got to follow Nancy’s dictum: just say no.

10 RESPONSES TO “THE PERFECT FISCAL STORM: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES, SOLUTIONS”

- Obsvr-1 | April 1, 2011 at 1:26 pm |100% spot on .. Now to get this through the thick skulls in Washington !!

- Anonymous | April 1, 2011 at 7:32 pm |Unless I misunderstand the ‘human condition’ as it relates to those in power in Washington, DC, the members of each branch of government are primarily interested in appeasing their primary benefactors (financial backers) in order to retain their own positions. There are several members of Congress who wish to ‘do the right thing’, however, they are ignored by the majority. The Republicans who are running the HoR and many governors’ offices haven’t a clue; their economics advisers do not understand MMT, nor could they care less. Terry Bouton’s recent book ‘Taming Democracy …) points out that, in the revolutionary war era, that segment of Pennsylvania social structure outside of the Philadelphia city limits favored rational economic policy; they were overruled by the elites including Robert Morris, Alex Hamilton, James Wilson and many other land speculators and elites who eventually ran the Federalist Party and dominated American politics from the beginning. The book title describes what the Federalists actually did; i.e., they ‘tamed’ democracy and instituted a system of exploitation at the so-called ‘beginning’ of the USA. The apparently rather recent recognition of the scams indicate that the mainstream media have been a handmaiden of the elites from the beginning. While we recognize some of the scams, what most don’t recognize is that similar misrepresentations by America’s political leaders have been going on for a long time.My impression is that MMT will only work when the administrators and regulators are properly qualified. The only way that might happen in the next century is for the advocates of MMT to initiate a very explicit and thorough educational, conceptual revolution. That might be accomplished by employing an educational/propaganda-style approach which effectively employs both visual and audio techniques so that anyone with a high school education could understand. Should such a program be conducted properly, there might be a chance. Otherwise, your guess would be as good as mine.

- Tom Hickey | April 1, 2011 at 7:48 pm |What’s so hard to understand about this? Oh right, to paraphrase Upton Sinclair, It is difficult to get a person to understand something when his bonus or campaign contribution depends upon his not understanding it.

- Thomas W | April 2, 2011 at 12:11 am |In talking about a lack of savings in the late 90’s (and since then), we seem to avoid the obvious answer. Bank savings accounts (or CDs or whatever) barely pay interest. Why save money and under 1% interest. Especially with the easy credit of recent years, along with routine “4% for the life of the balance” offers from credit card companies. It makes more sense to spend now rather than save. It’s even Keynesian to do so…I wonder how much of this is the change in credit markets. My parents lament people today not being responsible for their debts, but when my parents were starting out (mid 1950s) they couldn’t have gotten the credit available today. If credit had been as easy in the 1950s I imagine we’d have had the same debt problems as today. Easier credit is thanks to banks lowering lending standards, though that in turn results from changes in capital markets.You seem to belittle the issue of pensions for state workers. As Lowenstein’s “While America Aged” shows, defined benefit pension liabilities are going to be a major problem in the future. They are already a major reason for the demise of GM and some other companies. They are also routinely underfunded, both due to overly optimistic assumptions about investment returns during rising markets and the ease of putting off the problem. Unfortunately, pension liabilities will only get worse as people continue to live longer. The solution is limiting liability by moving to defined contribution (as private industry has done), raising the retirement age, dying younger (I’m waiting for conservatives to link “death panels” into pensions), or significantly raising taxes.

- The Arthurian | April 2, 2011 at 6:22 am |Why “Goldilocks,” and which are the Goldilocks years? thanks.Also, the link to the chart doesn’t work.ArtS

- Frank Lenk | April 3, 2011 at 6:24 pm |Is there a link to a more detailed explanation of how the chart above was derived? I have examined Scott Fullwiler’s July 26, 2009 post on this blog, and downloaded the NIPA accounts from BEA in an attempt to recreate the calculations – primarily Table 5.1. Saving and Investment by Sector for net private savings, Table 4.1. Foreign Transactions for the current account balance, and Table 3.1. Government Current Receipts and Expenditures for the public deficit. Despite my best efforts, I cannot get net private savings to equal the public deficit (as a positive number) plus the current account balance. My figures are off by anywhere from a few tens to a few hundreds of billions dollars. Can anyone offer some assistance? The tables are complicated,and perhaps I am not pulling from the correct lines.

- Economic Perspectives from Kansas City | April 3, 2011 at 7:58 pm |Frank,If you e-mail me offline, I’ll send you the excel file. keltons@umkc.edusk

- Ramanan | April 4, 2011 at 11:09 am |Frank Lenk,If you can check the Fed’s Z.1 Statistic … http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/current/z1.pdfTable F.1 has lines “Credit Market Borrowing” and “Credit Market Lending” … Lines 1 and Lines 25 (bold ones) are identical. (However for individual sectors they are not identical so a sector is a net-lender or a net-borrower.)

- Andy | April 4, 2011 at 5:17 pm |The stimulus should include infrastructure projects that actually put people to work. Tax breaks and unemployment insurance is just a stop gap measure that could be used while these projects are getting into the pipeline. Under current conditions people getting tax breaks are likely to spend them paying down their debts rather then creating demand. Corporations will probably use them to buy back their own stock until demand causes their now underutilized capacity to disappear. This is like pushing on a rope. Demand pull is what is needed.

- The Arthurian | April 5, 2011 at 1:05 pm |Andy says: “Under current conditions people getting tax breaks are likely to spend them paying down their debts rather then creating demand.”Art says: There is insufficient demand because too many dollars go to pay down debt. If the Fed, rather than paying good money to buy up bad debt, had been paying debt off for people, people would have the money they need to create demand. And creditors would have got their money back.Probably off topic.