Originally posted on January 24, 2016 at the New Economic Perspectives blog.

MONETARY BASE AND THE BALANCE SHEET OF THE FED.

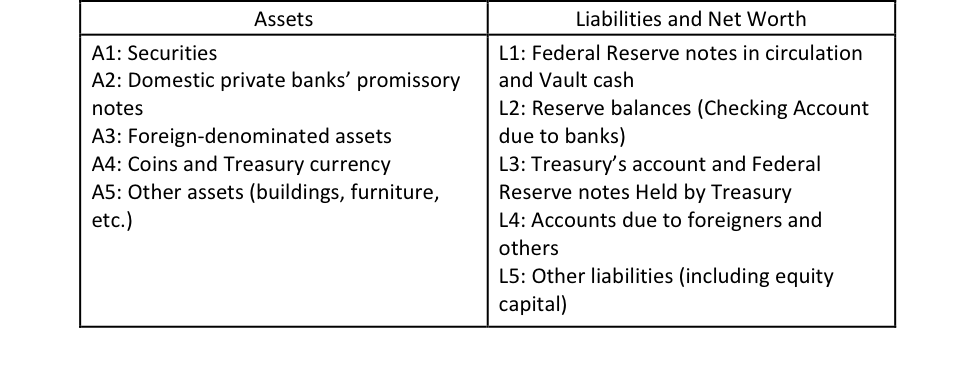

Post 2 examined the balance sheet of the central bank:

Now that we have an understanding of how the balance sheet of the Fed works, it is possible to go into the details of how the Fed operates in the economy in terms of monetary policy.

To understand what the Fed does, one first needs to define the monetary base and see how it relates to the Fed’s balance sheet. The post quickly looks at the difference between monetary base and money supply, and also looks more carefully at what reserves are.

The Monetary Base and the Money Supply

The monetary base (aka “high-powered money”) is defined as:

Monetary Base = Reserve balances + vault cash + cash in circulation

In its widest meaning, “in circulation” means any Federal Reserve Notes (FRNs) outside the Federal Reserve banks and any Treasury-issued cash outside Treasury. Economists prefer to use a narrower definition. Cash in circulation is any currency outside vaults of private banks (“vault cash”), of the Treasury, and of the Fed—what is held by “the public.”

Technically, cash means currency and coins. The Fed and Treasury use the word “currency” to mean paper money only. Currency in circulation includes mostly FRNs, but also some Treasury currency (United States notes, silver certificates) and national bank notes (issued prior to the creation of the Fed in 1913) that the Treasury still agrees to take at face value in payments of dues. The distinction between coins and currency is mostly statistical and does not have any analytical power. Post 15 shows that the material of which something is made is irrelevant to determine if it is a monetary instrument. This series uses the word cash and currency interchangeably.

To simplify, the U.S. monetary base can be reduced to:

Monetary base = L1 + L2

That is the monetary base is the sum of reserve balances and FRNs held by other entities than the Fed and the Treasury.

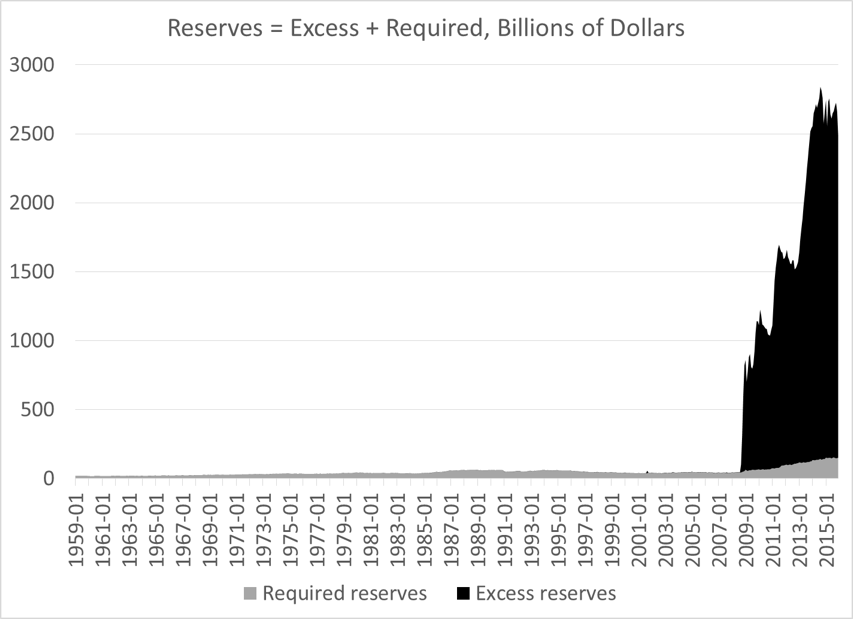

Until recently, currency in circulation was the largest component of the monetary base and it grew steadily to almost $1.4 trillion today, most of which are FRNs, and “between one-half and two-thirds of the value of U.S. currency in circulation is held abroad.” The global financial crisis led a large increase in reserve balances from about $24 billion on average from January 1959 to August 2008 to about $2.5 trillion today (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sources: H3 series (for reserve balances and currency in circulation out of Treasury and Fed Banks) and H6 series (for currency in circulation out of Treasury, Fed banks and private banks) at the Board of Governors.

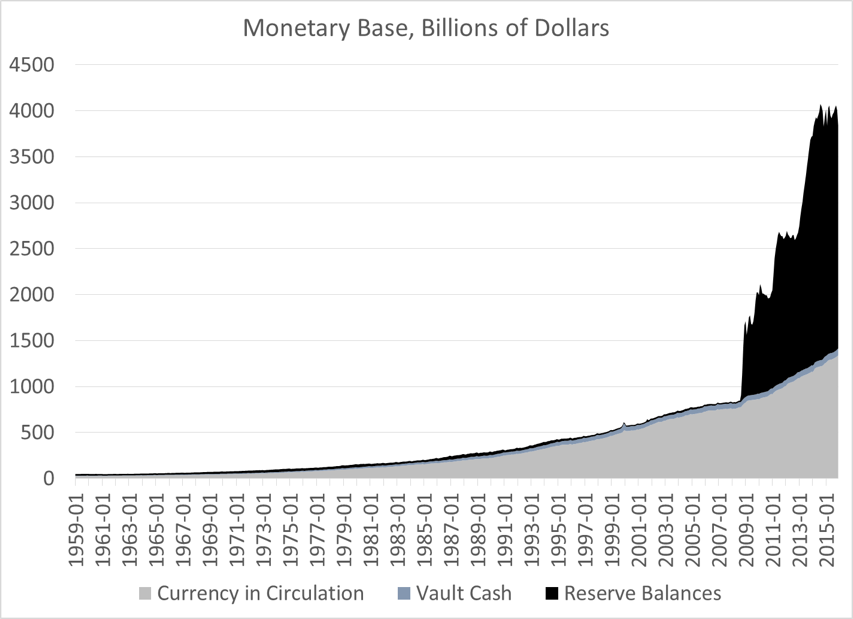

The monetary base is not the same thing as the money supply. Money supply means money held by non-bank economic units and outside the Treasury and other official foreign institutions. There are several ways to measure that and monetary aggregate M1 is the narrowest (Figure 2):

M1 = Cash in circulation + Private-bank checking accounts of non-banks, non-federal, non-official foreign economic units + others

M1 relates to the Fed’s balance sheet only via part of L1. FRNs in circulation have represented about 40% to 50% of M1 from the mid-1990s, 20 to 30% before that.

Figure 2. Source: Board of Governors, Series H.6

It is important to make a difference between the money supply and the monetary base because the central bank has no direct influence on the money supply. The Fed does not deal with the public directly, private banks do. Even for FRNs, private banks are in charge of injecting FRNs in the economy and they do so only if customers want to withdraw cash. In a 2010 interview Chairman Bernanke noted regarding the announced purchase of $600 billion of treasuries (aka “quantitative easing”):

One myth that’s out there is that what we’re doing is printing money. We’re not printing money. The amount of currency in circulation is not changing. The money supply is not changing in any significant way.

Translated in what is presented above, Bernanke states that L2 has gone up dramatically but that M1 has not changed. The Fed did not issue FRNs to the public (L1 is not going up), it just credited the accounts of banks by buying treasuries from them and, as Post 2 shows, banks cannot do much with reserve balances.

One should note that the Treasury’s account at the Fed (L3) and its accounts at private banks (called Treasury Tax and Loans accounts (TT&Ls)) are not part of the monetary base or the money supply. They are “funds.” The amount of dollars in the Treasury’s accounts are not counted in any definition.

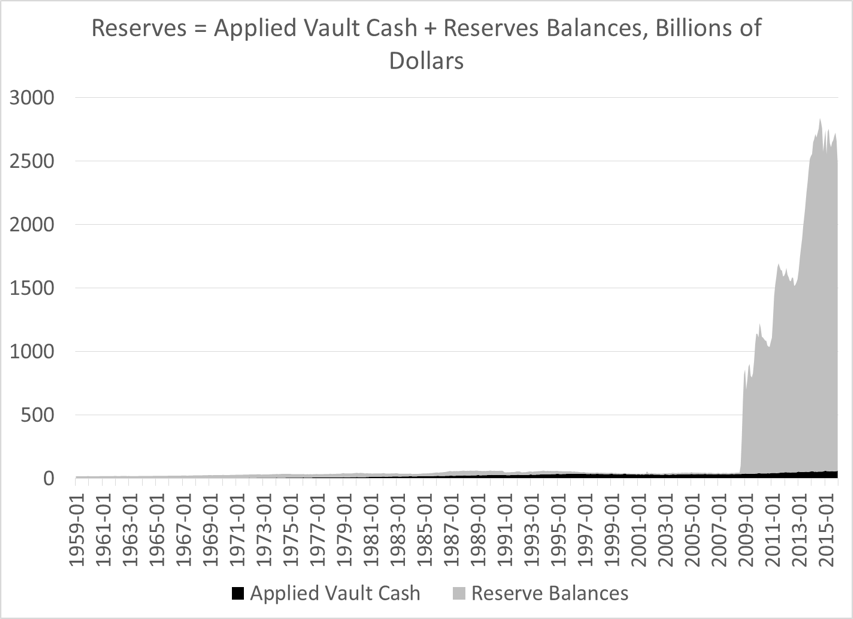

Reserves: Required, Excess, Free, Borrowed, Non-borrowed

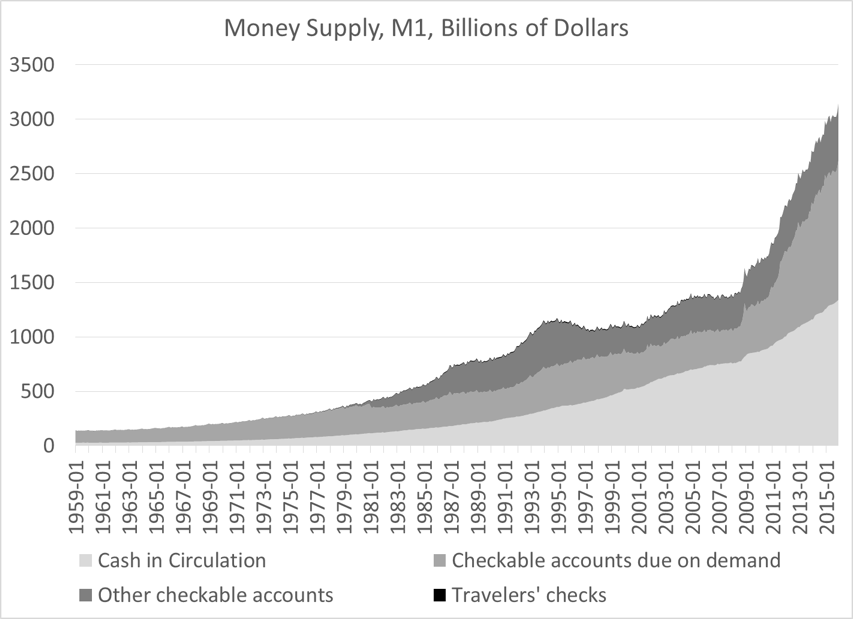

Within the monetary base, reserves are central to monetary-policy operations so this section studies a bit more carefully the reserve-side of the monetary base. Total amount of reserves is:

Total reserves = Reserves balances + applied vault cash = L2 + part of L1

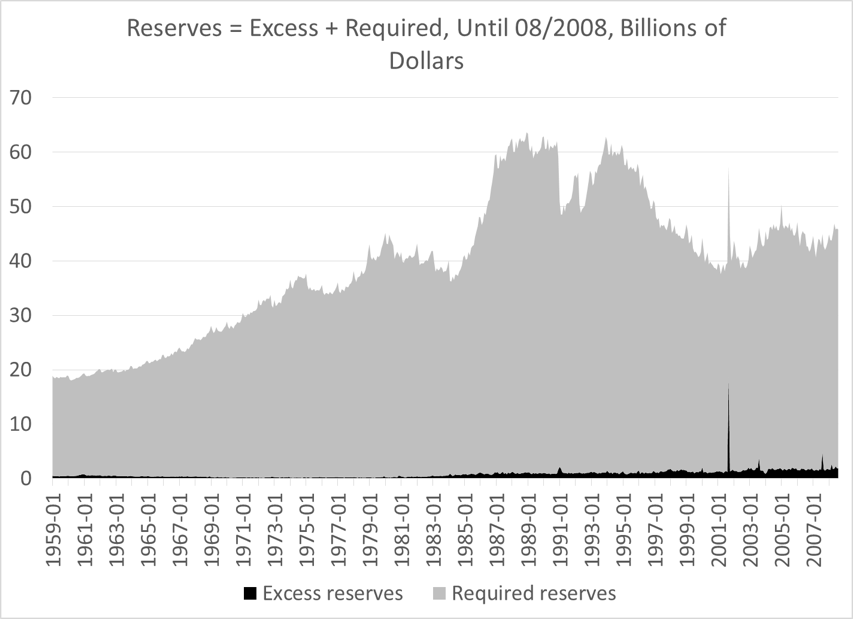

Applied vault cash are the FRNs that banks decide to use to calculate the amount of reserves they report to the Fed (the rest of vault cash is called “surplus vault cash”). From the 1990s and until the Great Recession, applied vault cash had represented the majority of total reserves and peaked to about 80% of total reserves. Since August 2008, reserves balances have been, by far, the main component of total reserves (Figure 3).

It is possible for reserve balances (L2) to go negative, i.e. the Fed allows banks to have an overdraft; however, the Fed expects that banks close any overdraft at the end of each day. If a bank cannot do it, the Fed charges a very high interest rate because the overdraft is a form of uncollateralized advance contrary to Discount Window advances. If the overdraft persists, the Fed may take a closer look at how the bank runs its business.

Total reserves can be decomposed into other categories than the form they take. One may also be interested in knowing how banks obtained their reserves. The Fed is the monopoly supplier of reserves and there are two ways for the Fed to provide reserves:

- Fed’s Discount Window advances funds by swapping promissory notes with banks (see Post 2): “borrowed reserves”

- Fed buys some assets from banks either permanently (“outright purchases”) or temporarily (“repurchase agreements”): “non-borrowed reserves”

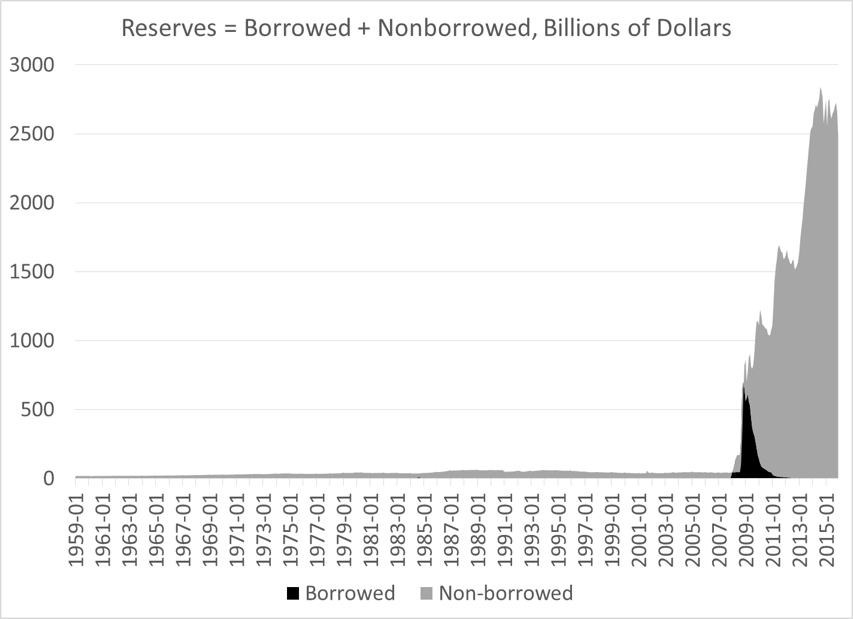

Total reserves = borrowed reserves + non-borrowed reserves

Non-borrowed reserves have been the main source of reserves (Figure 4) because the Fed discourages the use of the Discount Window (interest rate is higher and Fed may increase supervision if a bank comes to the Window too often). The stigma of going to the Window is so strong that, during the 2008 crisis, the Fed had to change its Discount Window procedures to entice banks that desperately needed reserves to come.

Finally, the total amount of reserves can be decomposed in terms of the uses of reserves. Banks in the United States must have a certain proportion of reserves relative to the amount of bank accounts they issue:

- Required reserves: amount of reserves banks must hold in proportion of the bank accounts they issued

- Excess reserves: whatever banks have in excess of required reserves.

Total reserves = Required reserves + excess reserves

Up until the crisis, required reserves were the overwhelming amount of total reserves (Figure 5). Excess reserves was virtually zero (Post 4 explains why). Up until the crisis, the amount of reserves was also relatively stable over decades and averaged $40 billion (Figure 6).

One may sometimes encounter the word “free reserves,” which just means the difference between excess reserves and borrowed reserves. Throughout this series, the most important categorization will be the last one: excess vs. required reserves.

Figure 3. Source: Board of Governors, Series H.3

Figure 4. Source: Board of Governors, Series H.3

Figure 5. Source: Board of Governors, Series H.3

Note: Non-borrowed reserves is negative during the peak amount of borrowed reserves. Non-borrowed reserves is measures by L1 – A2. A2 is borrowed reserves. For reasons not discussed in this blog, L1 became smaller than A2.

Figure 6. Source: Board of Governors, Series H.3

How does the monetary base change?

The monetary base will go up or down depending on what happens to the other items in the balance sheet of the Fed. Following the point that balance sheet must balance we have:

L1 + L2 = A1 + A2 + A3 + A4 + A5 – L3 – L4 – L5

So monetary base will be injected when:

- The Fed buys something (i.e. acquires an asset) from banks or the public

- Higher A1: Buying securities (T-bills, T-bonds, etc.)

- Higher A2: Advances of Federal Funds

- Higher A3: Buying foreign currency from private banks

- Higher A5: Buying a pizza, a building, or a service from someone

- The other Fed account holders spend in the US economy and Fed pays dividends to banks

- Lower L3: Treasury Spends

- Lower L4: US Exports

- Lower L5: Fed pays dividends to banks

The monetary base will be removed when opposite transactions occur. Buying coins from the Treasury does not change the monetary base because L3 goes up by the same amount as A4; it is an intra-federal government transaction. Let’s take a few examples:

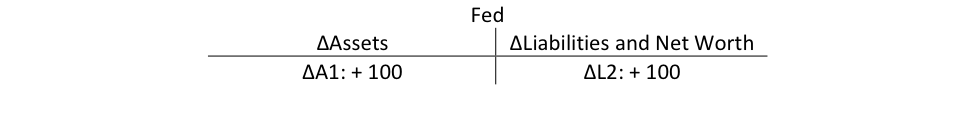

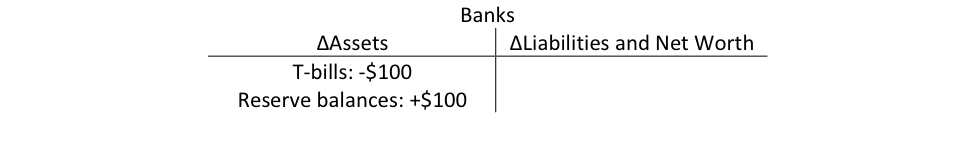

Case 1: The Federal Reserve buys T-Bills worth $100 from banks

You have just witnessed the creation of monetary base: The central bank credits the account of banks by typing “100” on the keyboard of a computer. The Fed could also have printed bank notes (ΔL1 = +$100) but purchases from banks are done electronically because of convenience.

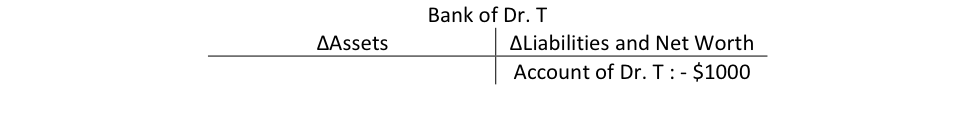

Case 2: Dr. T pays his income taxes worth $1000.

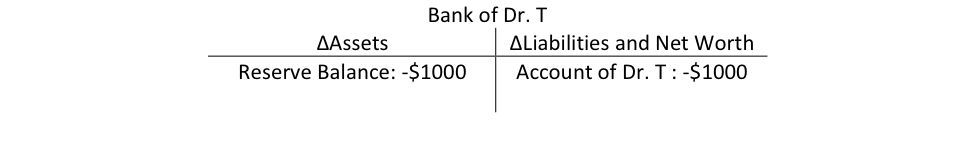

Assume that Dr. T still mails his income-tax paperwork with a check for the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The Treasury receives the check and brings it to the Fed (we ignore Treasury’s tax and loan accounts (TT&L) because that just complicates the analysis without adding any insights at this point. Post 6 studies the heavy interaction between the Treasury and the Fed). The Fed sends the check to the bank of Dr. T. and so the bank debits the bank account of Dr. T by $1000.

What is the offsetting operation on the bank’s balance sheet? The $1000 have to go to the Treasury. Given that we assumed that the Treasury only has an account at the Fed we know that the offsetting operation CANNOT BE (it would be if TT&Ls had been included):

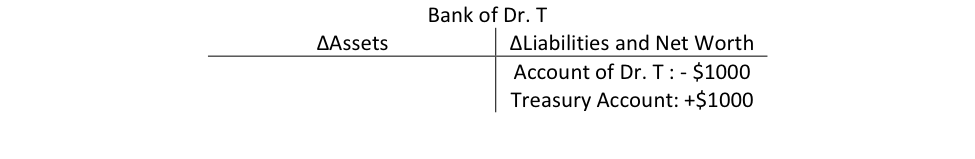

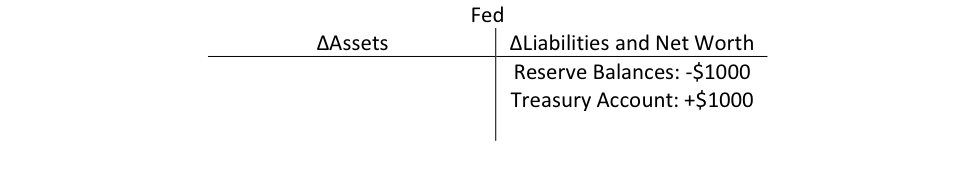

The Treasury only has an account at the Fed so the following will occur when the $1000 are transferred (which would be the second step if TT&Ls were included in the analysis):

But that again begs the question: What is the offsetting accounting entry on the balance sheet of the Fed? It cannot be “Account of Dr. T: -$1000” because Dr. T does not have an account at the Fed.

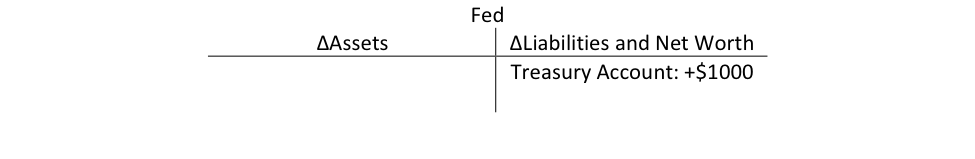

The answer is that when the Fed receives the check, it has a claim on Dr. T.’s bank. The bank settles that claim by giving up reserves and the funds are transferred into the account of the Treasury. Interbank claims (claims among private banks, and between the Fed and private banks) are always settled with transfers of reserves.

You have just witnessed the destruction of monetary-base: TAXES DESTROY MONETARY BASE. The central bank deleted $1000 in the reserve balance and keystroked $1000 in the account of the Treasury.

Of course, if the Treasury spends reserve balances are credited, and if Treasury spends more than its taxes then there is a net injection of reserves: FISCAL DEFICITS (government spending larger than taxes) LEAD TO A NET INJECTION OF RESERVES. Keep that in mind for Post 4.

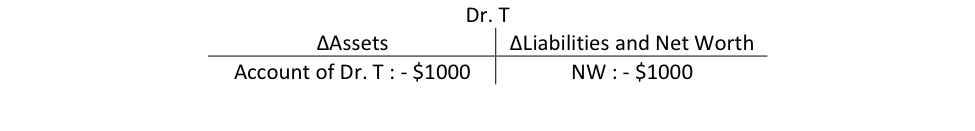

As a side note, one may note that Dr. T’s balance sheet changes as follows when taxes are paid:

Can the Fed issue an infinite amount of monetary base?

Yes it technically can given that the monetary base is composed of liabilities of the Fed. In practice though, the ability to inject reserves is constrained by the operational requirements of monetary policy. Post 4 shows that if the central bank issues reserves regardless of the needs of banks, it will not be able to achieve a specific policy interest rate it sets for itself unless it changes its operational procedures (which it did during the recent crisis).

At the origins of the Fed, some constraints were also put on the types of securities that the Fed could buy or that banks could pledge as collateral with their promissory notes to get an advance from the Discount Window. There was a fear that the Fed would over issue monetary base given its broad monetary power. Here is the language of the preamble of the 1913 Fed Act states:

To provide for the establishment of Federal reserve banks, to furnish an elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper, to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States, and for other purposes

“Elastic currency” just means that the Fed is able to create (and withdraw) monetary base at the will of banks and the public, i.e. in function of the needs of the economy. However, until 1932, the Fed operated under the Real Bills Doctrine (RBD). What that meant is that the Fed ought to only accept securities that “self liquidate” in A1 and as collateral for A2. Self-liquidating securities are those that are issued and destroyed in relation to economic activity. Firms issue securities to produce goods and services and repay them when Firms sell their production. The idea was that by tying monetary-base creation to production financing, the Fed would avoid inflationary tendencies that could come from an elastic currency. Monetary base (and so money supply as the thought of the time went) would grow in-sync with production.

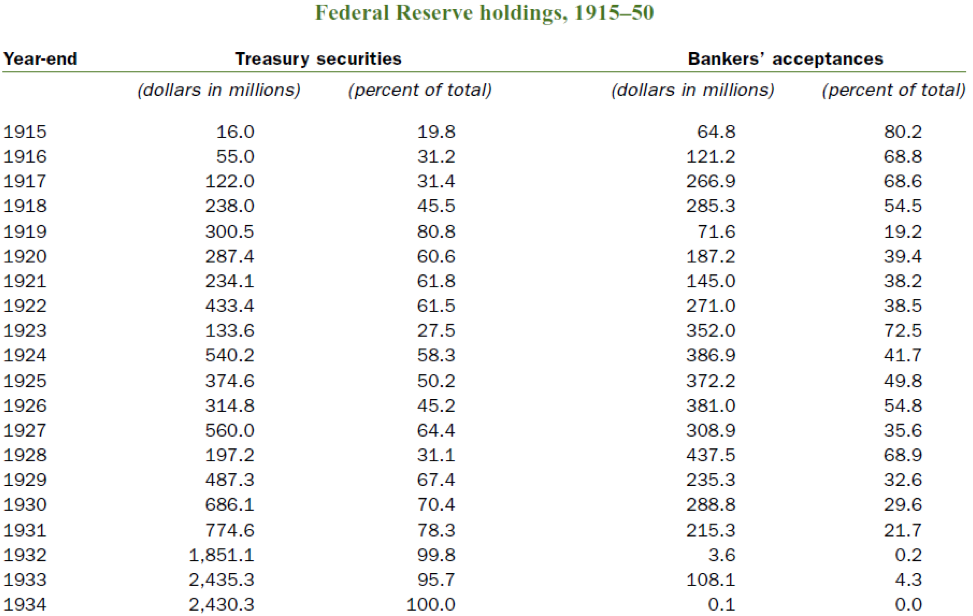

In practice, RBD never worked out well for both theoretical and practical reasons. WWI led to a large amount of treasuries held by the Fed. The Great Depression led to the elimination of the doctrine and the 1932 Banking Act widened dramatically the types of securities the Fed could accept if needed (Table 1).

Table 1. Holdings of securities by the Fed, 1915-1950

Source: Marshall’s Origins of the Use of Treasury Debt in Open Market Operations: Lessons for the Present

One of the problem of RBD is that it relied on private-indebtedness (issuances of securities by companies to finance production, “real bills”) for monetary policy to work. During a recession, banks did not have enough real bills to sale or pledge to the Fed because economic activity was dead so private issuance plunged. This is problematic because the scarcity of real bills limited the ability of banks to obtain reserves, just at the time when banks desperately needed some to counter bank runs and make interbank payments.

More recently, Dodd-Frank amended the Federal Reserve Act to constrain the capacity of the Fed to use “emergency powers,” i.e. its ability to accept any type of securities from anybody. This was a reaction to the advances provided to AIG that was not part of the Federal Reserve System. It was also a reaction to the opaqueness of the Discount Window operations during the crisis and how questionable some of the transactions were.

The Fed needs to be able to fight panics and the ensuing liquidity crisis when everybody and every banks are trying to get their hands on the currency. This is why the Fed was created. It can only do so by being able to buy, or accept as collateral, a wide verity of securities.

This leads to a final important point. Given that the Fed provides a safety valve in the financial system, it may lead to moral hazard. Financial-market participants may take more risks knowing that, if things go south, the Fed will intervene to avoid a collapse of the financial system. As a consequence the Fed must do two things:

- The Fed should also have ample regulatory and supervisory powers, AND it should use them. That is what the last bit of the preamble is all about.

- The Fed should discourage moral hazard and promote safe banking practices by accepting only securities that are of quality (that is based on sound underwriting and not in default) and from solvent institutions: The Fed exists to squash banking liquidity crisis (temporary inability to access funds), not to keep insolvent banks alive (permanent inability to pay creditors).

Unfortunately, these two conditions have not been met recently and moral hazard has increased dramatically.

The alternative is Andrew Mellon’s advice to Hoover: “liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, and liquidate real estate…it will purge the rottenness out of the system.” However, this belief in the self-cleansing of market mechanisms does not work, especially so in times of financial crisis and panic (see Part 14).

Done for today! Next post will dive into monetary-policy implementation by looking at the pre- and post-crisis monetary policy operations.

[Revised: 07/31/2016]