Pop the champagne, Congress approved funding the government for 2023. The omnibus bill did not, however, raise the nation’s ridiculous “debt” ceiling. Setting up a battle for later in 2023 where we can expect all the usual bravery, tact, and compassion Congress is known for. The U.S. Department of the Treasury reports that, “since 1960, Congress has acted 78 separate times to permanently raise, temporarily extend, or revise the definition of the debt limit – 49 times under Republican presidents and 29 times under Democratic presidents. Congressional leaders in both parties have recognized that this is necessary.”

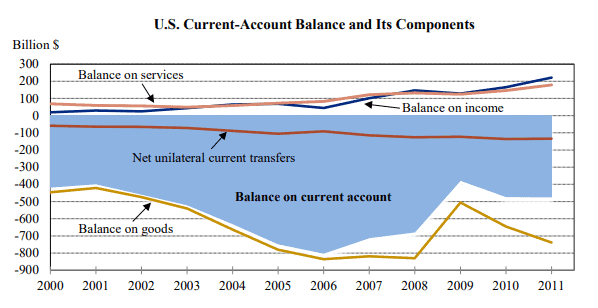

Beautifully simple are a sovereign nation’s sectoral balances (graph below). They readily demonstrate that the government’s negative is the public’s positive, and vice versa. The annual deficit or surplus is totaled into what is called the national “debt.”

Economics Professor Scott Fullwiler clarified the idea of a government “debt” ceiling as:

“…dumb on the face of it, of course, because there’s no reason to have a debt ceiling for the currency issuer. It’s dumb because we know the government deficit is the non-government sector surplus. So, you’re basically putting a limit on the non-government sector surplus, which is also dumb.”

Not only are we putting a limit on our surplus, our ability as a society to net save a little more money next year than last year, we are also putting a limit on our ability to mobilize. That should be particularly startling as we begin to move past the pandemic crisis but have not yet even begun to address the continuing humanitarian and climate crises. The reality is that as long as there are underutilized hands, idle factories, or just a more efficient way of doing something, a monetarily sovereign government undoubtedly has room for targeted spending.

We pretend, ridiculously, that there is a scarcity of the money that government legally creates and controls. The reality is that whenever the U.S. Congress approves spending, a schedule of auctions is adjusted by the Treasury and central bank, which will keep the Treasury’s account positive using bond sales for whatever portion is not deleted through taxes. System dynamicist Tyrone Keynes explained on Macro N Cheese that:

What the critics of MMT say is, well, the banks don’t just simultaneously buy the appropriate amount of bonds on the spot and swap that out. And they’re correct. They actually have auctions usually a week to a month before to account for that spending. But those reserves that they are going to use to buy those bonds were original reserves created by government spending in the past. So the big argument against MMT is that no, the banks are buying this from their own reserves. Those reserves were created by government spending in the first instance.

Whether in times of federal surplus or deficit, all federal spending is effectively new money, and all federal taxing is destroyed money. The very separation of the central bank and treasury is entirely unnecessary, as you can divide their duties but not the sole source of their authority. Warren Mosler explains that the Fed is the “score keeper for the dollar,” neither having or not having dollars, and describes the Fed’s duties as keeping a spreadsheet. Whether or not the keepers of this spreadsheet, a simple ledger, choose to type and delete or instead cut and paste is not the “gotcha” that MMT’s detractors think it is.

When the Treasury sells new securities, the private primary dealers—there are 25 of them as of this writing—are obligated to place “meaningful bids.” It says so in the Mitchell, Wray, and Watts Macroeconomics textbook, and it says so on the U.S. Treasury’s and Federal Reserve’s own websites. It is required, predetermined, that all new U.S. “debt” will be sold. Besides, why would the big financial institutions not oblige? They get free money for buying a bond from one government entity and selling it back to another.

The big banks turn some of their Federal Reserve balance into Treasury bonds for a higher return, the Treasury then has those reserves in its account to spend again, back into the banks as new dollar-denominated reserves which are then represented in consumer bank accounts as “dollars.” Interest is paid on both the banking sector’s holdings of reserves at the Fed and on bonds they bought from the Treasury, but for some reason only the latter is labeled as “debt.”

Bond sales are not about funding government. The U.S. Federal Reserve is a dinosaur, and it eats workers and defecates stagflation. As Steve Grumbine recently jabbed on The Rogue Scholar – “Bond sales are an anachronism… something we used to do that doesn’t matter anymore. Kind of like a tyrannosaurus’ arms are vestigial.”

There is a class of parasites, rentiers, that do not contribute to society. THAT is the purpose of bonds, of so-called “debt.” When interest rates rise it means more free money from Uncle Sam, when rates fall they use cheap credit and poor regulation to inflate asset bubbles.

What determines a “meaningful bid,” and how much will the financial sector reap? That’s entirely up to Uncle Sam. The Fed’s discount window is where the central bank sets the “overnight rate,” i.e., “federal funds rate,” on top of which other interest rates fluctuate, by providing short-term loans to private banks that otherwise would be forced to borrow from each other. Banks will happily swap central bank reserves for Treasury bonds at any rate above the overnight, although the aforementioned legal requirement makes that happiness rather moot. This is the cereal bipartisan working people strive to piss in, it is just hard to aim through the subterfuge.

Monetary policy today is conducted with the discount rate as the ceiling, and with the deposit rate serving as the floor. The discount rate is the interest they charge to cover inadequate reserves, thereby setting the maximum cost of loaning reserves between private banks. The deposit rate is the interest the Fed pays on a banks’ reserves. So, banks are only willing to settle amongst themselves inside this range. A bank with extra reserves will not loan them at a lower rate than that which they are already earning in interest, and a bank that is short on reserves will not borrow at a higher cost than the public rate at the Federal Reserve. They will not borrow above or loan below this interest-rate window. This space in between, the federal funds rate, sometimes referred to as the interbank target rate, gets an awful lot of press. This is what the media means when they say the Fed is “raising rates.”

The other side of needing money (costing more) is having money (paying more).

Randall Wray says:

“…the Fed is biased against labor. And the Fed doesn’t usually want to come right out and say it. But if you read the transcripts from their meetings, you know that they discuss this. That the way that they perceive interest rate policy working is by causing unemployment. So, what they’re trying to do now is cause unemployment in order to fight inflation…

This targeted rate is sometimes called the cost of money. Its value in alleviating inflation is overstated, and its being a blunt and ineffective instrument since inception is vastly understated. Bankers do not fund the government that chartered them, the government that maintains them at its will. Nor does the Federal Reserve, with the interbank rate, have an adequate tool to fight inflation. Raising the target, recession, these are fancy words for social murder. Modern Monetary Theory explains that a zero interest rate policy, referred to as ZIRP, should be set and left well enough alone. Rather than monetary policy, existing and proposed fiscal policies (such as the Federal Job Guarantee), are much more effective tools for targeting economic wellbeing.

The interest rate for the “debt,” like that for our mortgages or credit cards, fluctuates on top of this target rate. Post gold, bond payments had served as an interest floor, but that function was made redundant in 2008 when we started paying interest directly on federal reserves, as described above. We can keep some form of them around as a safe and stable means of savings if we choose. However, pretending they finance the legal controller of a fiat currency is to beat a 90-years-dead horse. A horse that, upon closer inspection, was a braying ass all along. Professor Fullwiler explains what would happen if we separated “debt” from the spending process:

“…what would happen is when the Treasury spends without issuing Treasurys, you would simply end up with interest-bearing Federal Reserve balances going into bank accounts. And it’s functionally the equivalent of issuing T bills, short-term Treasurys, because it’s basically an overnight interest-bearing account. And so you’re not printing money. It’s the equivalent of spending and issuing really, really short-term interest-bearing debt, is effectively what it is.”

What would happen if we separated U.S. bonds from U.S. spending, eliminated so-called “debt” and “debt ceilings,” recognized the nation’s resources as Uncle Sam’s only economic constraint? What if we replaced bonds with red ink, platinum coin seigniorage, or just set the base interest rate at zero, and hurried up with making civilization sustainable and financial parasitism unsustainable? What, fiscally, would trying to halt this sixth mass extinction entail? Not much other than the elimination of a murderous rentier class too long pretending that they serve a public purpose, a small price for saving people and planet. Wray explains on Macro N Cheese:

This was actually Keynes’ proposal to have a zero overnight interest rate.

His proposal was to euthanize the rentier class. You all know what euthanize means, mercy killing of the rentier. That is the class of people that live off collecting interest. He saw them as functionless in the economy. They don’t serve any useful function. So, let’s euthanize them. Now, Keynes didn’t really mean kill them. I want to make that clear. He just meant remove that income.

The key lesson of “debt” ceilings for dummies is that “debt” ceilings are for dummies.

Great article. Thank you.