The Political Economy under Fascism should scare us. It is all too familiar.

They say little if anything about the class policies of fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. How did these regimes deal with social services, taxes, business, and the conditions of labor? For whose benefit and at whose expense?

-Michael Parenti, Blackshirts and Reds

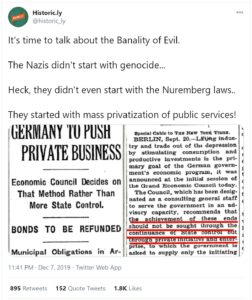

It’s time to talk about the Banality of Evil. The Nazis didn’t start with genocide. Heck, they didn’t even start with the Nuremberg Laws. Our education system and popular media focus on the most horrific, the most dramatic, and the most apparent aspects of Fascism. However, Fascism begins in a much less dramatic fashion. In the beginning,Fascism is banal, and to many of us, it is oddly familiar.

Before the rise of Fascism, both Italy and Germany had a robust social safety net and public services. In Italy, the trains were nationalized. They ran frequently and served many rural villages as early as 1861. The telecom industry was nationalized in 1901. Phone lines and public telephone services were universally available. In 1908, the life insurance industry was nationalized. For the first time, even poor Italians could ensure that their family could be taken care of if they died a premature death.

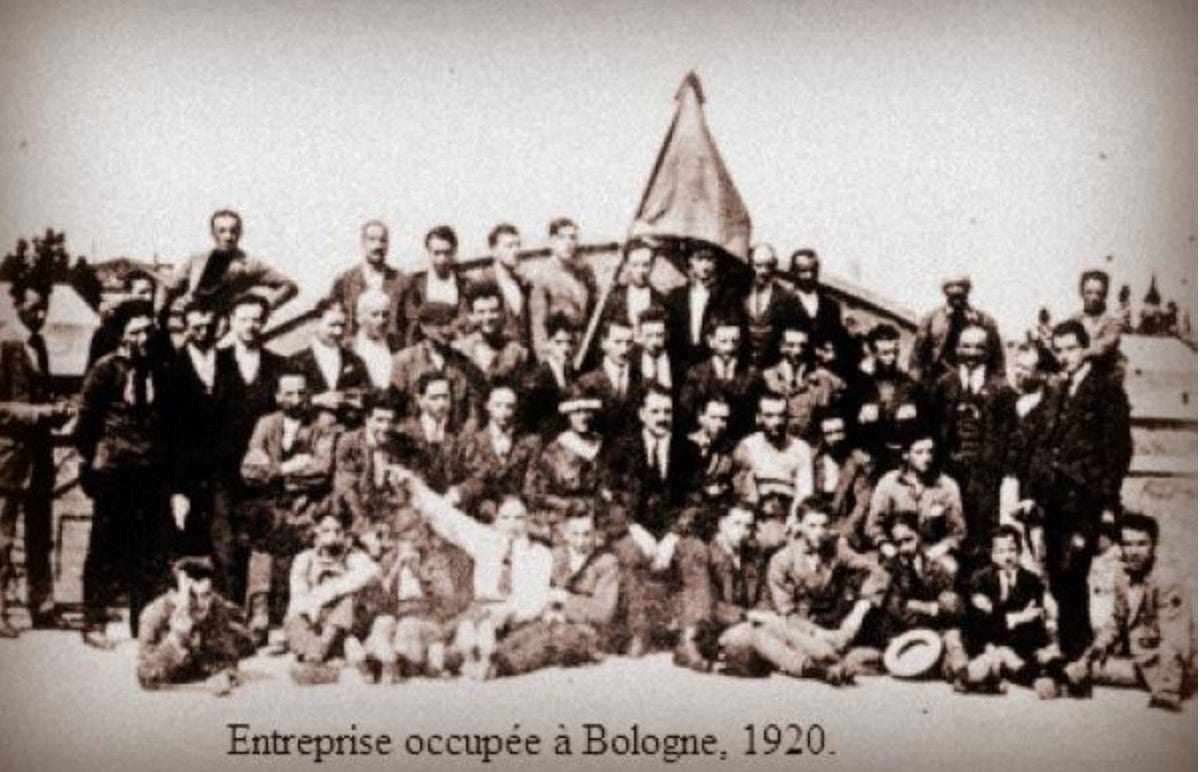

Between 1919 and 1921, Italy went through a time of worker liberation that has been dubbed as Bienno Rosso. Italian workers had formed factory co-ops where they shared the profits. Large landlords were replaced by cooperative farming. Workers received many concessions: higher wages, fewer hours, and safer workplace conditions.

Similarly, in Germany, Otto von Bismarck nationalized healthcare, making it available to all Germans in 1871. Bismarck also provided old-age pensions as public social security. Under Otto Von Bismarck, child labor was abolished, as well as providing public schools to all children. Germany inherited a national railway system from the Prussian empire. Germany’s Social Democratic Party grew strong during 1890s. In response, the Kaiser implemented worker protection laws in 1890. After World War I, the Social Democrats’ influence was strong. Germany had an active union membership. This created a robust safety net: “Decree on Collective Agreements, Worker and Employees Committees and the Settlement of Labor disputes” allowed for collective bargaining, legal enforcement of labor contracts as well as social security for disabled veterans, widows, and dependents. In 1918, unemployment benefits were given to all workers in Germany.

Policies of Fascism

Benito Mussolini became Prime Minister in October 1922. Nazis rose to power in 1933 in Germany. Mussolini convened a meeting of his cabinet and immediately decided to privatize all the public enterprises. On December 3, 1922, they passed a law where they promised to reduce the size and function of the government, reform tax laws and also reduce spending. This was followed by mass privatization. He privatized the post office, railroads, telephone companies, and even the state life insurance companies. Afterward, the two firms that had lobbied the hardest: Assicurazioni Generali (AG) and Adriatica di Sicurtà (AS), became a de-facto oligopoly. They became for-profit enterprises. The premiums increased, and poor people had their coverage removed.

After the trains were privatized, the services became slower and more irregular, contrary to the popular myth.

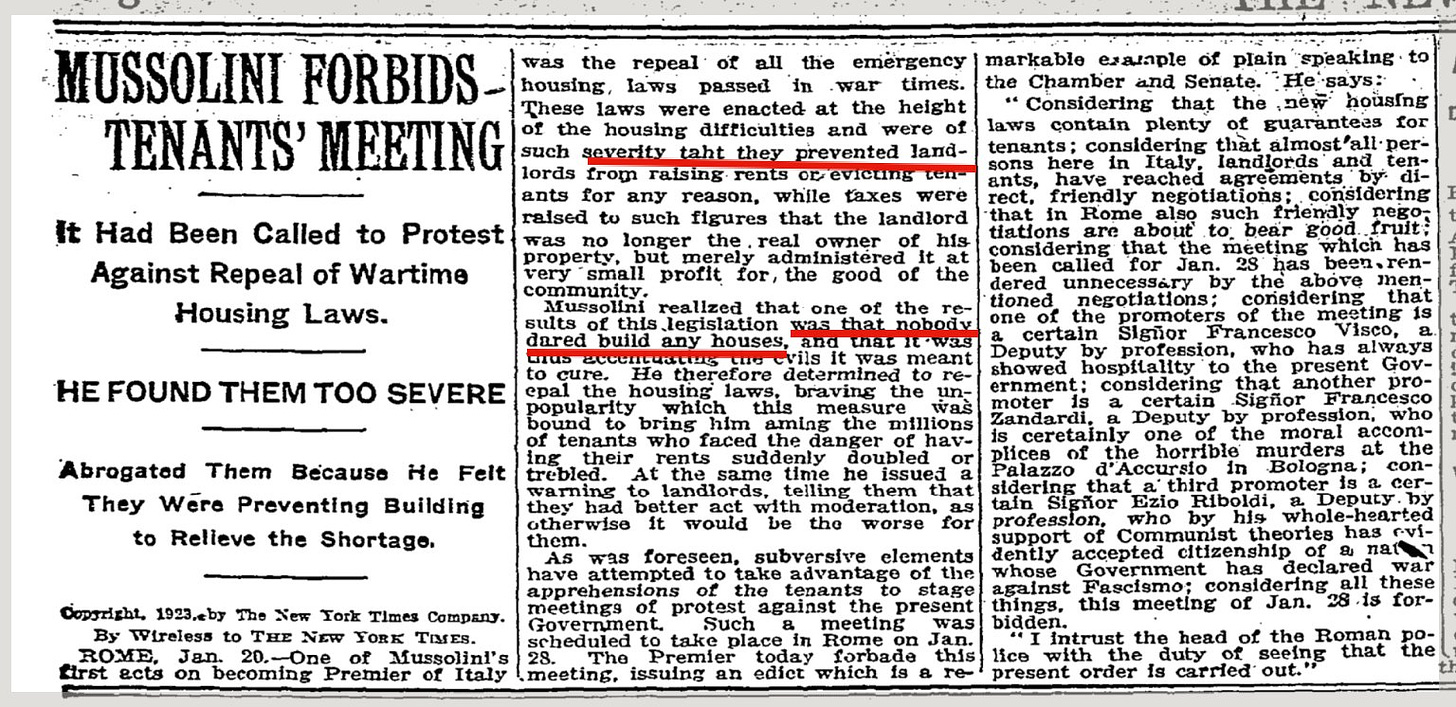

In January 1923, Mussolini eliminated rent-control laws. His reasoning ought to be familiar since that is the same reasoning used in many contemporary editorials against rent control laws. He claimed rent control laws prevent landlords from building new housing. When tenants protested, he eliminated tenants’ unions. As a result, rent prices increased wildly in Rome, and many families became homeless. Some went to live in caves.

Once more, these policies allowed landlords to increase their profit and holdings while they severely hurt the poor.

To remove “government waste,” Mussolini removed the federal government from remote areas in Italy. This meant that rural farmers, peasants, and workers no longer had the protection of the federal government against abuse from agribusiness. Instead, they were entirely under the mercy of big businesses.

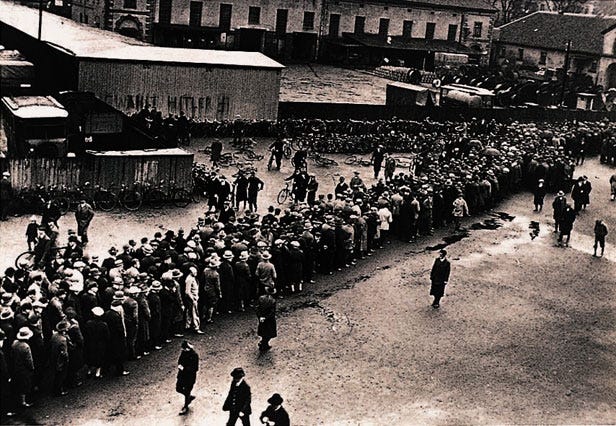

Hitler’s economic policy was Mussolini’s policy on steroids. In the 1920s, the NSDAP was a minor party. In the 1932 elections, the Nazi Party did not have an outright majority. According to the Nuremberg Trial transcripts, on January 4, 1933, bankers and industrialists had a secret backroom deal with then-Chancellor Von Papen to make Hitler the Chancellor of Germany in a coalition. According to banker Kurt Baron von Schröder:

The negotiations took place exclusively between Hitler and Papen. [ . . . ] Papen went on to say that he thought it best to form a government in which the conservative and nationalist elements that had supported him were represented together with the Nazis. He suggested that this new government should, if possible, be led by Hitler and himself together. Then Hitler made a long speech in which he said that, if he were to be elected Chancellor, Papen’s followers could participate in his (Hitler’s) Government as Ministers if they were willing to support his policy which was planning many alterations in the existing state of affairs. He outlined these alterations, including the removal of all Social Democrats, Communists and Jews from leading positions in Germany and the restoration of order in public life. Von Papen and Hitler reached agreement in principle whereby many of the disagreements between them could be removed and cooperation might be possible. It was agreed that further details could be worked out later either in Berlin or some other suitable place

In February 1933, as Chancellor, Hitler met with the leading German industrialists at the home of Hermann Goring. There were representatives from IG Farben, AG Siemens, BMW, coal mining magnates, Theissen Corp, AG Krupp, as well as a locust of Bankers, investors, and other Germans belonging to the top 1%. During this meeting, Hitler said, “Private enterprise cannot be maintained in the age of democracy.”

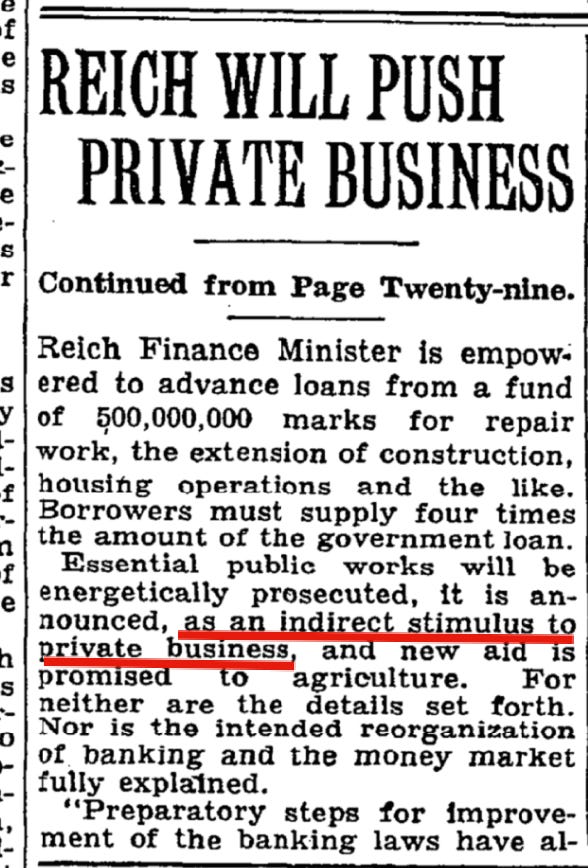

In 1934, Nazis outlined their plan to revitalize the German economy. It involved reprivatization of significant industries: railways, public works project, construction, steel, and banking. On top of that, Hitler guaranteed profits for the private sector, and so, many American industrialists and bankers gleefully flocked to Germany to invest.

The Nazis had a thorough plan for deregulation. The Nazi’s economist, stated,” The first thing German business needs is peace and quiet. It must have a feeling of absolute legal security and must know that work and its return are guaranteed. The interferences in a business which occurred at first, perhaps as a result of too much zeal, have become intolerable.”

Germany had the most robust social-democratic movement, and consequently, the best worker protections in Europe codified by law. This was a significant impediment to businesses “operating freely without interference.”

The Nazis ensured that businesses weren’t hampered by too much “regulation.” On May 2, 1933, Adolf Hitler sent his Brown Shirts to all union headquarters. Union leaders were beaten, and sent to prison or concentration camps. On top of that, the Nazi party, expropriated union funds (money workers paid for union membership). The union leadership was replaced by Hitler’s goons, who were inherently unsympathetic to unions to help bargain away all collective bargaining rights.

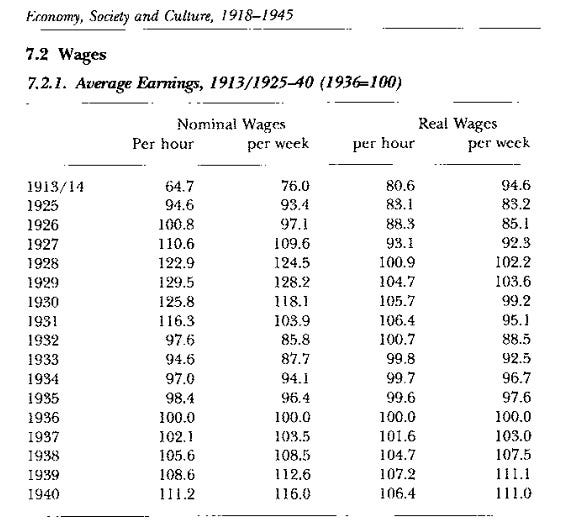

On January 20, 1934, the Nazis passed the Law Regulating National Labor. The act explicitly took power away from the government to set minimum wages and working conditions. The act stated, “The leader of the enterprise makes the decisions for the employees and laborers in all matters concerning the enterprise, as far as they are regulated by this law.” Employers lowered wages and benefits. Workers were banned from striking or engaging in other collective bargaining rights. Worker conditions were so deteriorated that with the head of the AFL visited Nazi Germany in 1938, he compared the life of an average worker to that of a slave. Workers in Nazi Germany worked longer hours for lower wages.

Hitler repeatedly cut social provisions, which included food rations to the poor under the guise of combating “idolatry.” In 1934, the homeless were rounded-up en-masse and sent to concentration camps as a way of getting rid of “public nuisance.”

Nazis also privatized medicine. In fact, one of Hitler’s economists was the head of a private insurance company. These private for-profit health insurance companies immediately started to profit from Anti-Semitism. In 1934, they eliminated reimbursements for Jewish physicians, which allowed them to profit.

Of course, many of these industrialists, who were tried in Nuremberg, claimed that they were “afraid” of Hitler. Still, evidence during the trial showed that these industrialists weren’t merely complicit in Hitler’s worst atrocities, but they actively campaigned for and lobbied for it. In Hitler, they found a willing partner who would let them profit at any cost.

Fascism isn’t the merger of corporations and government that is too vague, and too easy to confuse. Fascism is government functions being replaced by private corporations. Fascism is when the public good is replaced by private profit.

In spite of all this overwhelming, first-hand evidence, which is freely available through the Nuremberg Trial Transcripts in English, why does this myth of “government-overreach” persist? Many unions had independent media and news services. Many of them did not survive McCarthyism. Therefore, we are deprived of a first-hand account of the horrors of Fascism. The industrialists who benefited from Hitler hired PR companies to spin Hitler’s deeds in the best possible light. For example, IG Farben hired Lee Ivy, the father of PR, to whitewash the deeds of Nazis in the American corporate press. Of course, providing positive public relations for Fascism, was an industry that flourished in the US all on its own after World War 2.

As Corey Robin wrote in The Reactionary Mind, “Every once in a while, however, the subordinates of this world contest their fates. They protest their conditions, write letters and petitions, join movements, and make demands. Their goals may be minimal and discrete-better safety guards on factory machines, an end to marital rape-but in voicing them, they raise the specter of a more fundamental change in power. They cease to be servants or supplicants and become agents, speaking and acting on their own behalf. More than the reforms themselves, it is this assertion of agency by the subject class-the appearance of an insistent and independent voice of demand-that vexes their superiors.”

Perhaps, structurally, that is the best way to understand the truth about Fascism.

Republished with permission. Original text can be found at the Historic.ly Substack.